Decimus Junius Juvenalis (l. c. 55-138 CE), better known as Juvenal, was a Roman satirist. He wrote five books, containing 16 satires, each of which criticized a different element of Roman society, whether it was poor housing, the patron/client relationships, the presence of Greeks in the city, the raising of children, prayer, or the arrogance and vanity of the city's women. Although earlier poets such Horace (Quintus Horatius Flaccus, 65-8 BCE) and Gaius Lucillius (180-103 BCE) wrote satire, Juvenal was the first author to devote himself entirely to satire. Written between 110 and 130 CE, around the same time as Tacitus' Annals, the satires are filled with both hatred and anger: hatred for the old aristocrats who controlled the city and anger at how the impoverished were treated. His outbursts towards the corruption he saw prevalent in Roman society and human cruelty are major themes throughout his satires. Rome, in Juvenal's eyes, was inhabited by degenerates and its virtue had all but perished.

Early Life

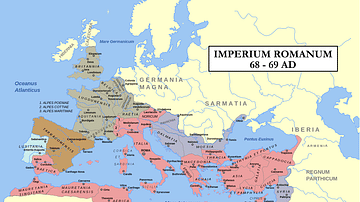

Juvenal was born around 55 CE to a middle-class family in the small town of Aquino near Rome. Although little is known of his early life, it is believed that he may have begun an administrative career, eventually becoming a soldier during the reign of Roman emperor Domitian (r. 81-96 CE). Unfortunately for Juvenal, he ran afoul of the moody emperor when he insulted one of Domitian's court favorites. For his crime, the young satirist was exiled to Syene in Egypt. When he returned to Rome in 96 CE after the assassination of Domitian, he focused his energies on writing. It was in his five books of satire where he would vent his anger at Rome and Roman citizens.

His resentment affected his perception of both the city and its people. Without the means to support himself, he was forced to seek the assistance of a patron as a client. Later, he questioned whether the insults one received at dinner were worth it. During the reign of Emperor Hadrian (r. 117-138 CE), he rose above his poverty and bought a farm near Tivoli, but money, land, and servants did not affect his attitude, and his assessment of the city and its citizens would not change. This outlook is evident throughout all of his 16 satires.

Works

Juvenal wrote five books of satire:

- Book I - Satires 1-5

- Book II - Satire 6

- Book III - Satires 7-9

- Book IV - Satires 10-12

- Book V - Satires 13-16 (the last one is incomplete)

In his first book of five satires, written around 110 CE during the reign of Trajan (r. 98-117 CE), he condemned the vice and crime prevailing in Rome, the patron/client relationship, and the decadence and wealth of the city's elite. Although he tried to avoid speaking of those in power, he did occasionally betray this ideal: veiled references in his first satire are believed to be about Domitian.

In Satire 3, Juvenal spoke through a friend named Umbricius. He attacked a multitude of different problems: the city's corruption, its poor housing, and the presence of deceitful foreigners, most notably the Greeks:

Now let me speak of the race that our rich men dote on most fondly. These I avoid like the plague, let's have no coyness about it. Citizens, I can't stand a Greekized Rome. (Gochberg, 500)

To Juvenal, poverty hindered a man's merit. He wrote:

Poverty's greatest curse, much worse than the fact of it, is that it makes men objects of mirth, ridiculed, humbled, embarrassed. (Gochberg, 504)

In his third satire, he also criticized the horrible housing conditions of the city where those on the top floors had little, if any, protection against rain and fire. He wrote:

… Rome is supported on pipestems, matchsticks; it's cheaper, so, for the landlord to shore up his ruins, patch up the old cracked walls, and notify all the tenants they can sleep secure, though the beams are in ruins above them. (Gochberg, 505)

Although he would eventually rise above his own poverty, he never forgot the time he spent depending on the handouts of others, the very people he learned to despise. Later, he would write of this humbling experience in one of his satires. In the opening lines of his fifth satire, he asked:

If you're not yet ashamed of the way you live. If you think that the highest good is still to live off another's leavings …. (Satire 5 Lines 1-2).

In Satire 6, he criticized Rome's women, their arrogance, vanity, and cruelty in some 600 lines. Other satires attacked the wretchedness and poverty of the city's intellectuals who could not find decent rewards for their labors (Satire 7), and the cult of hereditary nobility (Satire 8). Criticizing the city's fabled origins and the pompous nature of its citizens, he attacked the city's aristocrats, namely the patricians, who boasted of their family trees, dating back centuries to the founding of the city.

Though you can unroll the family tree, and trace your name back … and whoever your first ancestor might have been, he was still a herdsman, or performed some other task I'd rather not mention. (Satire 8 Lines 272 – 275).

In Satire 10, he spoke of human ambitions, wealth, power, and glory, and how, instead of these, one should pursue a sound body, mind, and heart. After speaking of the foolish extravagances of the rich in Satire 11, he admonished parents in Satire 14 who taught their children about greed. In Satire 15, having heard of a riot in Egypt, he spoke of human cruelty and came to the conclusion that humans are far crueler than animals. In the final unfinished Satire 16, he had hoped to address the privileges of the professional soldiers.

Writing Style

Classicist Edith Hamilton in her book The Roman Way wrote of Juvenal and his contemporary Publius Cornelius Tacitus (l. c. 56 - c. 118 CE). In her words, the great literature of the first two centuries brought about its own destruction. During this time, when Rome was a dying city, the Roman literature of the period was almost dead except for the works of three individuals: Tacitus, the historian; Seneca (l. 4 BCE - 65 CE), the Stoic philosopher and playwright; and Juvenal, the brilliant but bitter satirist. Unlike Seneca who saw purity and goodness, both Tacitus and Juvenal saw Rome as evil, without a single, mitigating factor. Hamilton saw Juvenal as a proud but poor man living in a city where the poor were treated with insolence, even by slaves. She wrote that he was a sensible genius who hated himself for accepting table scraps tossed to him by men he hated.

Reading through the five books of satire, one easily sees the anger that filled Juvenal. After returning to Rome from his exile in Egypt, an already angry man sees his Rome through a new set of eyes. Having lost everything, he is forced to live in dangerous, decaying housing and eat handouts from people he grew to detest. Eventually, he escaped his own poverty, but his hatred for the city and its people remained until his death around 138 CE. As evident throughout his writing, his hatred of the city's women makes it obvious why no one can find mention of a wife or family.

Legacy

Whether or not his bitter satires alienated those in the literary community, he was not well-received by other poets of his age. It was not until the time of the Christian author Tertullian (c. 155 - c. 240 CE) that he was read and quoted. He gained belated notoriety in the Middle Ages and the Renaissance. Later, others, such as Giovanni Boccaccio (1313-1375 CE), author of the Decameron, and the English poet Lord Byron (1788-1824 CE), began to read and imitate him. Although forgotten during his time, his memory has been preserved through many of his quotable catchphrases such as "… a sound mind in a sound body", "Who will guard the guards themselves?", "…the itch for writing", and "The greatest reverence is due to a child."