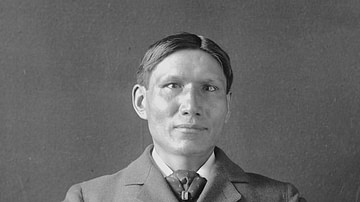

In his Indian Heroes and Great Chieftains (1916), Sioux author and physician Charles A. Eastman (also known as Ohiyesa, l. 1858-1939), includes a brief biography of the Sioux chief Sitting Bull (l. c. 1837-1890). While some of Eastman's claims are unsupported elsewhere, his work is viewed as a valuable source on the life of the great Native American leader.

Eastman drew on stories he had heard in his youth for his work and, as he says, on interviews with Sitting Bull's family, those who had known him, and even on an 1884 meeting with the man himself. Still, he makes some claims, such as how Sitting Bull approved the Fort Laramie Treaty of 1868 and then traveled to Washington, D.C., which have no outside support and seem untenable. Eastman's piece runs to over 4,000 words and so has been edited below for space considerations, but the complete online work will be found in the External Links section following this article.

In the full piece, Eastman also claims that Sitting Bull was given his name when, as a youth, he pushed a large buffalo calf, who had attacked him, to a sitting position – "and from this incident was derived his familiar name" (107). Actually, Sitting Bull was given his name by his father – who was known as Sitting Bull – and gave the youth his own name when the boy attained manhood – then taking the name Jumping Bull; his son would then go on to make the name Sitting Bull famous.

Text

Aside from these two questionable claims, Eastman's account is recognized as a more or less accurate depiction of the great Hunkpapa Sioux holy man, warrior, leader, and cultural hero. The following is taken from Eastman's Indian Heroes and Great Chieftains, 1939 edition, republished in 2016:

It is not easy to characterize Sitting Bull, of all Sioux chiefs most generally known to the American people. There are few to whom his name is not familiar, and still fewer who have learned to connect it with anything more than the conventional notion of a bloodthirsty savage. The man was an enigma at best. He was not impulsive, nor was he phlegmatic. He was most serious when he seemed to be jocose. He was gifted with the power of sarcasm, and few have used it more artfully than he…

It is a mistake to suppose that Sitting Bull, or any other Indian warrior, was of a murderous disposition. It is true that savage warfare had grown more and more harsh and cruel since the coming of white traders among them, bringing guns, knives, and whisky...The common impression that the Indian is naturally cruel and revengeful is entirely opposed to his philosophy and training. The revengeful tendency of the Indian was aroused by the white man…

Remember that there were councils which gave their decisions in accordance with the highest ideal of human justice before there were any cities on this continent; before there were bridges to span the Mississippi; before this network of railroads was dreamed of! There were primitive communities upon the very spot where Chicago or New York City now stands, where men were as children, innocent of all the crimes now committed there daily and nightly. True morality is more easily maintained in connection with the simple life. You must accept the truth that you demoralize any race whom you have subjugated.

From this point of view, we shall consider Sitting Bull's career. We say he is an untutored man: that is true so far as learning of a literary type is concerned; but he was not an untutored man when you view him from the standpoint of his nation. To be sure, he did not learn his lessons from books. This is second-hand information at best. All that he learned he verified for himself and put into daily practice. In personal appearance he was rather commonplace and made no immediate impression, but as he talked, he seemed to take hold of his hearers more and more. He was bull-headed; quick to grasp a situation, and not readily induced to change his mind. He was not suspicious until he was forced to be so. All his meaner traits were inevitably developed by the events of his later career.

Sitting Bull's history has been written many times by newspaper men and army officers, but I find no account of him which is entirely correct. I met him personally in 1884, and since his death I have gone thoroughly into the details of his life with his relatives and contemporaries. It has often been said that he was a physical coward and not a warrior. Judge of this for yourselves from the deed which first gave him fame in his own tribe, when he was about twenty-eight years old.

In an attack upon a band of Crow Indians, one of the enemy took his stand, after the rest had fled, in a deep ditch from which it seemed impossible to dislodge him. The situation had already cost the lives of several warriors, but they could not let him go to repeat such a boast over the Sioux!

"Follow me!" said Sitting Bull, and charged. He raced his horse to the brim of the ditch and struck at the enemy with his coup-staff, thus compelling him to expose himself to the fire of the others while shooting his assailant. But the Crow merely poked his empty gun into his face and dodged back under cover. Then Sitting Bull stopped; he saw that no one had followed him, and he also perceived that the enemy had no more ammunition left. He rode deliberately up to the barrier and threw his loaded gun over it; then he went back to his party and told them what he thought of them.

"Now," said he, "I have armed him, for I will not see a brave man killed unarmed. I will strike him again with my coup-staff to count the first feather; who will count the second?"

Again, he led the charge, and this time they all followed him. Sitting Bull was severely wounded by his own gun in the hands of the enemy, who was killed by those that came after him. This is a record that so far as I know was never made by any other warrior…

When Sitting Bull was a boy, there was no thought of trouble with the whites. He was acquainted with many of the early traders…All the early records show this friendly attitude of the Sioux, and the great fur companies for a century and a half depended upon them for the bulk of their trade. It was not until the middle of the last century that they woke up all of a sudden to the danger threatening their very existence…They utterly refused to cede their lands; [but]…they were willing to let [the white man] alone as long as he did not interfere with their life and customs, which was not long…

Sitting Bull joined in the attack on Fort Phil Kearny [during Red Cloud's War] and in the subsequent hostilities; but he accepted in good faith the treaty of 1868, and soon after it was signed, he visited Washington with Red Cloud and Spotted Tail, on which occasion the three distinguished chiefs attracted much attention and were entertained at dinner by President Grant and other notables. He considered that the life of the white man as he saw it was no life for his people but hoped by close adherence to the terms of this treaty to preserve the Big Horn and Black Hills country for a permanent hunting ground. When gold was discovered and the irrepressible gold seekers made their historic dash across the plains into this forbidden paradise, then his faith in the white man's honor was gone forever, and he took his final and most persistent stand in defense of his nation and home. His bitter and, at the same time, well-grounded and philosophical dislike of the conquering race is well expressed in a speech made before the purely Indian council before referred to, upon the Powder River. I will give it in brief as it has been several times repeated to me by men who were present.

"Behold, my friends, the spring is come; the earth has gladly received the embraces of the sun, and we shall soon see the results of their love! Every seed is awakened, and all animal life. It is through this mysterious power that we too have our being, and we therefore yield to our neighbors, even to our animal neighbors, the same right as ourselves to inhabit this vast land.

"Yet hear me, friends! we have now to deal with another people, small and feeble when our forefathers first met with them, but now great and overbearing. Strangely enough, they have a mind to till the soil, and the love of possessions is a disease in them. These people have made many rules that the rich may break, but the poor may not! They have a religion in which the poor worship, but the rich will not! They even take tithes of the poor and weak to support the rich and those who rule. They claim this mother of ours, the Earth, for their own use, and fence their neighbors away from her, and deface her with their buildings and their refuse. They compel her to produce out of season, and when sterile she is made to take medicine in order to produce again. All this is sacrilege.

"This nation is like a spring freshet; it overruns its banks and destroys all who are in its path. We cannot dwell side by side. Only seven years ago we made a treaty by which we were assured that the buffalo country should be left to us forever. Now they threaten to take that from us also. My brothers, shall we submit? or shall we say to them: ‘First kill me, before you can take possession of my fatherland!'"

…He has been called a "medicine man" and a "dreamer." Strictly speaking, he was neither of these, and the white historians are prone to confuse the two. A medicine man is a doctor or healer; a dreamer is an active war prophet who leads his war party according to his dream or prophecy. What is called by whites "making medicine" in war time is again a wrong conception. Every warrior carries a bag of sacred or lucky charms, supposed to protect the wearer alone, but it has nothing to do with the success or safety of the party as a whole. No one can make any "medicine" to affect the result of a battle, although it has been said that Sitting Bull did this at the battle of the Little Big Horn.

When Custer and Reno attacked the camp at both ends, the chief was caught napping. The village was in danger of surprise, and the women and children must be placed in safety. Like other men of his age, Sitting Bull got his family together for flight, and then joined the warriors on the Reno side of the attack. Thus, he was not in the famous charge against Custer; nevertheless, his voice was heard exhorting the warriors throughout that day.

During the autumn of 1876, after the fall of Custer, Sitting Bull was hunted all through the Yellowstone region by the military…The army report says: "Sitting Bull wanted peace in his own way." The truth was that he wanted nothing more than had been guaranteed to them by the treaty of 1868—the exclusive possession of their last hunting ground. This the government was not now prepared to grant, as it had been decided to place all the Indians under military control upon the various reservations.

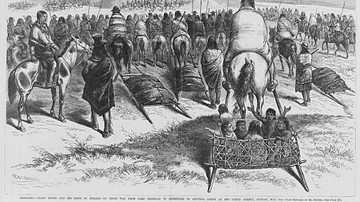

Since it was impossible to reconcile two such conflicting demands, the hostiles were driven about from pillar to post for several more years, and finally took refuge across the line in Canada, where Sitting Bull had placed his last hope of justice and freedom for his race… Sitting Bull was not moved by fair words; but when he found that if they had liberty on that side, they had little else, that the Canadian government would give them protection but no food, that the buffalo had been all but exterminated and his starving people were already beginning to desert him, he was compelled at last, in 1881, to report at Fort Buford, North Dakota, with his band of hungry, homeless, and discouraged refugees. It was, after all, to hunger and not to the strong arm of the military that he surrendered in the end.

In spite of the invitation that had been extended to him in the name of the "Great Father" at Washington, he was immediately thrown into a military prison, and afterward handed over to Colonel Cody ("Buffalo Bill") as an advertisement for his "Wild West Show." After traveling about for several years with the famous showman, thus increasing his knowledge of the weaknesses as well as the strength of the white man, the deposed and humiliated chief settled down quietly with his people upon the Standing Rock Agency in North Dakota, where his immediate band occupied the Grand River district and set to raising cattle and horses…

When the Commissions of 1888 and 1889 came to treat with the Sioux for a further cession of land and a reduction of their reservations, nearly all were opposed to consent on any terms. Nevertheless, by hook or by crook, enough signatures were finally obtained to carry the measure through, although it is said that many were those of women and the so-called "squaw-men", who had no rights in the land. At the same time, rations were cut down, and there was general hardship and dissatisfaction. Crazy Horse was long since dead; Spotted Tail had fallen at the hands of one of his own tribe; Red Cloud had become a feeble old man, and the disaffected among the Sioux began once more to look to Sitting Bull for leadership.

At this crisis a strange thing happened. A half-breed Indian in Nevada promulgated the news that the Messiah had appeared to him upon a peak in the Rockies, dressed in rabbit skins, and bringing a message to the red race. The message was to the effect that since his first coming had been in vain, since the white people had doubted and reviled him, had nailed him to the cross, and trampled upon his doctrines, he had come again in pity to save the Indian. He declared that he would cause the earth to shake and to overthrow the cities of the whites and destroy them, that the buffalo would return, and the land belong to the red race forever! These events were to come to pass within two years; and meanwhile they were to prepare for his coming by the ceremonies and dances which he commanded.

This curious story spread like wildfire and met with eager acceptance among the suffering and discontented people. The teachings of Christian missionaries had prepared them to believe in a Messiah, and the prescribed ceremonial was much more in accord with their traditions than the conventional worship of the churches. Chiefs of many tribes sent delegations to the Indian prophet; Short Bull, Kicking Bear, and others went from among the Sioux, and on their return, all inaugurated the dances at once. There was an attempt at first to keep the matter secret, but it soon became generally known and seriously disconcerted the Indian agents and others, who were quick to suspect a hostile conspiracy under all this religious enthusiasm. As a matter of fact, there was no thought of an uprising; the dancing was innocent enough, and pathetic enough, their despairing hope in a pitiful Savior who should overwhelm their oppressors and bring back their golden age.

When the Indians refused to give up the "Ghost Dance" at the bidding of the authorities, the growing suspicion and alarm focused upon Sitting Bull, who in spirit had never been any too submissive, and it was determined to order his arrest. At the special request of Major McLaughlin, agent at Standing Rock, forty of his Indian police were sent out to Sitting Bull's home on Grand River to secure his person (followed at some little distance by a body of United States troops for reinforcement, in case of trouble)…They entered the cabin at daybreak, aroused the chief from a sound slumber, helped him to dress, and led him unresisting from the house; but when he came out in the gray dawn of that December morning in 1890, to find his cabin surrounded by armed men and himself led away to he knew not what fate, he cried out loudly:

"They have taken me: what say you to it?"

Men poured out of the neighboring houses, and in a few minutes the police were themselves surrounded with an excited and rapidly increasing throng. They harangued the crowd in vain; Sitting Bull's blood was up, and he again appealed to his men. His adopted brother, the Assiniboine captive whose life he had saved so many years before, was the first to fire. His shot killed Lieutenant Bull Head, who held Sitting Bull by the arm. Then there was a short but sharp conflict, in which Sitting Bull and six of his defenders and six of the Indian police were slain, with many more wounded. The chief's young son, Crow Foot, and his devoted "brother" died with him…

Thus ended the life of a natural strategist of no mean courage and ability. The great chief was buried without honors outside the cemetery at the post, and for some years the grave was marked by a mere board at its head. Recently some women have built a cairn of rocks there in token of respect and remembrance.