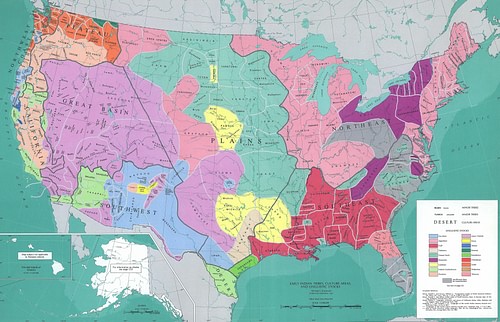

The Sioux are a native North American nation who inhabited the Great Plains region of, roughly, modern Colorado, Montana, Nebraska, North Dakota, South Dakota, and Wyoming. They are one of the many nations referred to as Plains Indians who lived in the region for approximately 13,000 years before the arrival of the Europeans in the 17th century.

The Sioux are originally from the Mississippi River Valley as well as the Great Lakes region, but wars with the Iroquois and Ojibwe Nations forced their migration west. The name "Sioux" derives from a French interpretation of an Ojibwe reference. The actual name for the people is Oceti Sakowin (People of the Seven Council Fires) or Oceti Sakowin Oyate (People of the Seven Council Fires Nation), referencing the seven original Sioux bands (tribes) who brought the coals from their individual fires to kindle the collective fire at council meetings. These tribes, known as the Seven Bands, are:

- Mdewakanton

- Sisseton (also as Sistonwan)

- Teton (also as Tetonwan)

- Wahpekute

- Wahpeton (also as Wahpetonwan)

- Yankton (also as Ihanktown)

- Yanktonai (also as Ihanktowana)

The tribes came to be referenced as Dakota or Lakota (and formerly Nakota, though this has now been challenged), which means "ally" or "friend." These seven are related to other tribal nations through language (Siouan) and culture. Originally hunter-gatherers, the Sioux adopted an agrarian lifestyle c. 700/900 CE after the introduction of maize (corn) from Mesoamerica but continued to hunt and maintain a semi-nomadic social model as they followed wild game, mainly buffalo. Their traditional socio-cultural model changed in the late 17th/early 18th century with the arrival of European firearms and their mastery of the horse (brought to North America in the 16th century by the Spaniards), making them one of the nations designated by modern scholars as belonging to the "Horse Culture" of North America.

As with all the other Native American nations, contact with Europeans negatively impacted the Sioux culture from the beginning, but more so in the 19th century when American expansionist policies demanded more of their ancestral lands. Resistance was led by great Sioux leaders including Red Cloud (l. 1822-1909), Sitting Bull (l. c. 1837-1890), and Crazy Horse (l. c. 1840-1877), while others like Black Elk (l. 1863-1950) supported them. The greatest Sioux victory was the Battle of Little Bighorn in June 1876, and the greatest defeat was the Wounded Knee Massacre of 1890, which ended Sioux resistance and led to their relocation on reservations.

Name, Language & Nation

The people later known as "Sioux" first inhabited the Mississippi Valley region until Iroquois aggression and conflicts with the Ojibwe forced their migration west to the area of modern Minnesota and Wisconsin.

The site Native Hope gives the origin for the name "Sioux":

According to Albert White Hat, elder and language teacher, the word "Sioux" stems from the westward expansion of the French fur traders in the Northern Wisconsin Lakes region and Minnesota. When the Dakota people told the fur traders they could come no further west, the traders went to the Ojibwe and asked, "Who are these people?" An Ojibwe elder moved his hands like a snake and said, "natowessiwak." An interpreter said, "The snake people." However, what the Ojibwe elder actually meant was "the people of the snake-like river" (Mississippi). In French, to pluralize a word, "-oux" is often added, and soon the Dakota were known as the "Nadouessioux" or "little snakes." Over time, the term was shortened from "Nadouessioux" to "Sioux." (1)

Scholar Adele Nozedar writes, "the first time that they were recorded as the 'Sioux' was when the French interpreter Jean Nicolet noted the word in 1640" (439). Prior to that time, they were known by the name they called themselves, Oceti Sakowin and Dakota/Lakota. The original seven tribes are related to others through the Siouan language family, including:

- Arikara

- Crow

- Hidatsa

- Iowa

- Kansas

- Mandan

- Missouri

- Omaha

- Osage

- Oto

- Ponca

- Quapaw

These different tribes formed pacts of friendship and alliance and joined the original seven. This nation is known as Dakota in the eastern dialect and Lakota in the western dialect. Until recently, Nakota was cited as the name in the middle dialect, but this has been challenged and fallen out of use in some circles. The Sioux spread further west and south from the Minnesota/Wisconsin region even before French incursions from modern Canada began encroaching on their lands in the 17th century.

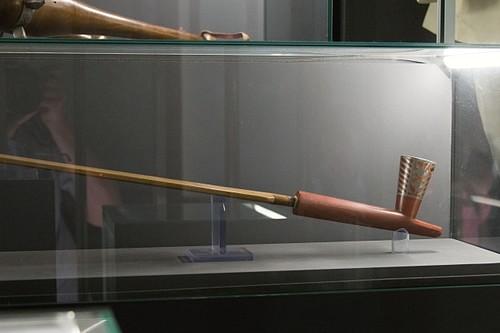

Religion, Ritual, & Sun Dance

The daily life of the Sioux is informed by their religious beliefs, which holds that the Great Spirit (Wakan Tanka) created all things, informs all things, and is the unifying force of the universe that maintains all things. Central to their spiritual beliefs is the chanunpa (ceremonial pipe/holy pipe) and the lela wakan ("very sacred") bundle of tobacco, given to them by White Buffalo Calf Woman, a supernatural figure who came to show them their relationship to Wakan Tanka and how to honor and maintain that connection. Along with the pipe and tobacco, she taught them the seven sacred rites they should observe and how the chanunpa was to be used in these ceremonies and at other times:

The holy woman demonstrated how to present the pipe to the Earth, the sky, and the sacred directions, before explaining that the circular stone bowl of the pipe, with its carving of a buffalo calf, represented Earth and all the four-footed animals that walked upon it. Its wooden stem, rising from the center of the bowl, stood for everything that grows and represented a direct link between the Earth and the sky. Twelve spotted eagle feathers hanging from the pipe represent all the creatures of the air. "Whenever you smoke this pipe," the woman said, "all these things join you, everything in the universe; all send their voices to Wakan Tanka, the Great Spirit. Whenever you pray with this pipe you pray for and with all things."

(Zimmerman, 236)

The seven sacred rites the pipe is used with are:

- Keeping of the Soul (also given as Keeping and Releasing of the Soul)

- The Purification Rite

- Crying for a Vision

- The Sun Dance

- The Making of Relatives

- The Girl's Coming of Age

- The Throwing of the Ball

Different sources present these in different order. The above order comes from scholar Larry J. Zimmerman (in agreement with most others) who explains them:

The first rite, the "keeping and releasing of the soul" is used to "keep" the soul of a dead person for a number of years until it is properly released, ensuring a proper return to the spirit world. The second ritual is the "sweat lodge", a purification rite. The third, "crying for a vision", lays down the ritual pattern of the Lakota vision quest. The fourth is the communal ceremony known as the Sun Dance [celebrated to awaken the earth and give thanks to the sun]. The fifth is the "making of relatives", a ritual joining of two friends into a sacred bond. The sixth is the girl's puberty ceremony. The final ritual is called "throwing the ball", a game representing Wakan Tanka and the attaining of wisdom. The ceremonies of the Lakota enacted [White Buffalo Calf Woman's] injunction to revere the Great Spirit.

(237)

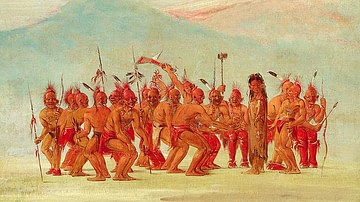

Each ritual is just as important as the others, but the Sun Dance involves the entire community and is considered essential for the renewal of the earth, a healthy harvest, prosperity in the hunt and in warfare, tribal unity, and maintaining a solid connection with the Great Spirit. The ritual was (and is) observed in early summer, usually June, and involved the entire community. The dance was initiated by a man or woman who either had been told in a vision they should take the lead, were asking the Great Spirit for some favor, were giving thanks for a gift received, or for the general welfare of the community. Whatever the motivating factor was, the good of the many was the prime focus. In thanking the Great Spirit for the healthy birth of one's child, for example, one would also be giving thanks for the healthy births of all the children in the community.

Although one person announced the dance, there was a part to play in the ritual for everyone in the community. Children helped prepare the area for the dance by clearing and cleaning, women built the structure, and men erected the central pole, killed the animals that would be used, and those who would be participating directly, spiritually prepared themselves for the dance.

A temporary lodge was built with a pole at the center symbolizing the connection between the Earth and sky and this was topped by the head of a buffalo killed by a skilled hunter with a single shot. The buffalo was considered a sacred animal and a source of life and so was honored at the center of the ritual. Leather thongs attached to the top of the pole would later be threaded through either the shoulders or pectorals of those who had volunteered to suffer sacrifice either in hopes of receiving a vision or for the good of the community or as a way of expressing their gratitude.

These people would dance around the pole, swinging freely from the thongs – which they could not touch with their hands – until they broke loose and fell to the ground, at which time they were carried to sage beds to rest and, hopefully, receive visions. People would fast and pray, and during the dance – which could often last days or up to two weeks – some people refused to drink or drank sparingly. The focus of the dance was, essentially, gratitude, connection, and revival – whether awakening oneself, the earth, the spirits, or the community – but in this, as in all things, the good of the many was understood as more important than the individual so even if one were participating in hopes of a vision, that vision was recognized as benefiting everyone – not just the recipient.

Daily Life, Government, & Gender Roles

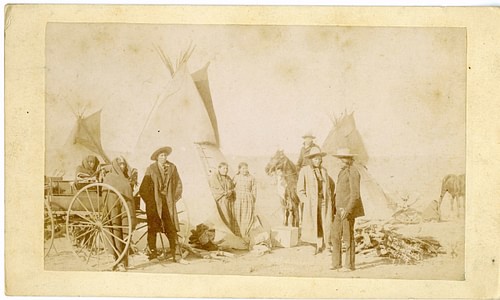

The daily life of the Sioux reflected this understanding, as everyone had a part to play in providing for the overall good of the community. Men hunted, protected the village, made war, and participated in the rituals of fraternities that would train them as warriors, hunters, guardians, leaders, or diplomats, recognizing their natural inclinations or skills and developing them. Women made the clothes, raised the children (until the boys were old enough to be instructed by their fathers or uncles), built the tipi (teepee) or home, raised and took down the tipi when camp was broken, owned most or sometimes all the objects in the home (as it was her domain), planted and harvested crops, and engaged in trade agreements. Children played games but were also expected to contribute after a certain age by helping to gather firewood, prepare hides, or fetch water.

Women could divorce husbands who proved to be poor providers or for any other reason by simply removing his belongings from her teepee and throwing them on the ground. The man would then be homeless unless relatives took pity on him. A man could have more than one wife as long as he could provide equally for each woman and showed her the same level of respect. Women could also participate in government, which was characterized by a communal gathering of the nations once a year in summer where the coals of each of their individual village fires were brought to kindle a central fire, concerns were raised, discussed, and decisions made.

Each individual village or community had its own version of this communal gathering of leaders who had been chosen by the tribe based on their personal virtues. Only those who exemplified the values of the community, such as loyalty, honor, courage, and wisdom, would be chosen as leaders and could remain so only as long as they continued to exhibit these qualities.

Although gender roles were well-defined for males and females, there was also the recognition of a third gender which was neither. In the modern era, these people are known as Two-Spirits. A Two-Spirit is a man or woman who identifies as the opposite sex. An individual with a male body might be visited by a vision just before or during puberty, revealing that person's actual gender, and they would then be known as a winkte – short for the Lakota term winyanktehca ("one who wants to be a woman"). These people were highly valued by the community and performed the tasks and assumed a role associated with females.

As with everyone else, a Two-Spirit was (and is) understood as having something of value to contribute to the benefit of the community, and so there was no judgment attached to someone who, today, would be labeled 'trans' or 'gay'. A winkte was valued as highly as anyone else in the community, sometimes more so, especially if they exhibited great wisdom, artistic ability, or generosity of spirit.

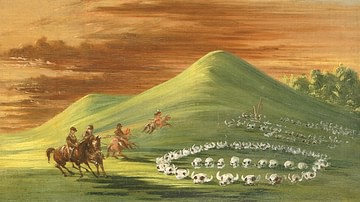

Warfare, the Horse & American Expansion

The Sioux, like any of the Native American nations, were not always peaceful, accepting, and forgiving, however, and frequently made war or mounted raids on their neighbors. Wars were fought on foot until the Sioux mastered the horse, which they were already well aware of by c. 1700. The horse revolutionized Sioux travel, hunting, and warfare. It became, in fact, a cause for wars – or at least raids – on other tribes as the more horses one had, the greater one's wealth and prestige.

War parties were also organized to protect one's hunting grounds, avenge a perceived insult, or for honor in battle. The Sioux regularly took the scalps of their enemies in battle and, afterwards, held a Scalp Dance, which honored the ones who had been killed as well as those of the Sioux who had fallen in battle. Mourners were encouraged to tell the story of the one they had lost during this ritual so he would be remembered and honored.

When the European immigrants/Americans began pushing further west, the mounted Sioux warrior was among the most feared, and wars were then fought either defensively – to protect one's land and community – or offensively – to drive out Anglo settlers that had taken land and resources without permission. The so-called Sioux Wars (or Plains Indians Wars) were fought between 1854 and 1890 – from the Grattan Fight (a massacre of 30 US soldiers and their civilian interpreter) to the Wounded Knee Massacre in which over 250 Sioux men, women, and children were killed.

Conclusion

The Wounded Knee Massacre broke Sioux resistance to the genocidal policies of the United States government, and the people were moved onto reservations – tracts of land not of their own choosing – despite the many treaties signed by United States representatives promising them peace on their ancestral lands. Zimmerman writes:

At the core of each Native culture is an abiding reverence for the region in which the people live. The terrain there is sacred, a source of identity and strength…This topographical pattern is repeated across the regions – and it is one reason why forced relocation was so culturally destructive. (155)

Today the Sioux live on reservations spanning a mere 7,800 square kilometers (3,000 sq. mi) of the vast territory they once called home in the modern states of Minnesota, Montana, Nebraska, North Dakota, and South Dakota, as well as reservations in Canada. Although the Sioux were promised they could live peacefully on these reservations, proposed pipeline projects through their lands, which threaten the environment and their health – such as the controversial Keystone XL Pipeline – follow the same paradigm established by the US government in the 18th and 19th centuries of breaking promises in the interests of profit.

The most famous example of US government infamy – regarding only the Sioux, not to mention the many other nations – is when they were promised their sacred territory of the Black Hills by the Fort Laramie Treaty of 1868 and the US government then broke that treaty once gold was found in the hills in 1874. In 1980, the US Supreme Court ruled that the Black Hills were acquired illegally by the United States and agreed on reparation to be paid of over $100 million, which was placed in an account. That $100 million has now grown with interest to over a billion dollars, but the Sioux refuse to accept it because the land was never for sale. The Sioux do not want the money; they only want justice and their land back.