Red Cloud (Makhpiya-luta, l. 1822-1909) was an Oglala Lakota Sioux chief, statesman, and military strategist who became the only Native American leader of the Plains Indians to win a war against the United States. Red Cloud's War (1866-1868) forced the US government to agree to Native demands without stipulation, establishing the Great Sioux Reservation in 1868.

Red Cloud is often referenced as the Chief of the Sioux Nation, following descriptions given of him in the 19th century, but, as Sioux government was decentralized, he was one of many chiefs and only the leader of the band known as the Bad Faces. In his youth, he had been part of a trading expedition that camped near Fort Laramie and so acquired a greater knowledge of the white man than most, if not all, of his contemporaries in leadership. According to modern scholars, including Bob Drury and Tom Clavin, this gave him greater insight during his later interactions with the US government and its representatives.

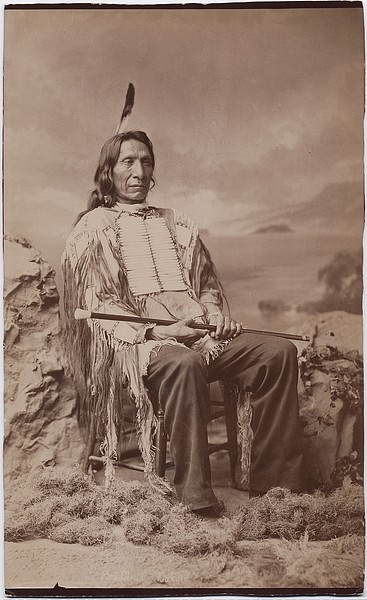

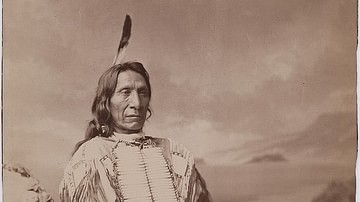

Following his victory over the United States in Red Cloud's War, he negotiated the closing of the Bozeman Trail through Sioux territory, the abandonment of US forts, and created the Great Sioux Reservation, which stretched across modern-day South Dakota, up into North Dakota, and down into Nebraska. He traveled to Washington, D.C. twice to negotiate with President U. S. Grant (served 1869-1877) and became so well-known as a representative of his people that he is the most widely photographed Native American of his time.

His efforts to establish peaceful coexistence with the white man eventually failed owing to the US government's policies of ignoring every treaty anytime it suited them and advancing their agenda to confine the Sioux to small reservations. The Dawes Act of 1887 broke up the Great Sioux Reservation, and although Red Cloud opposed this move, he did not encourage armed resistance and helped his people adjust to the reservation system. He died of natural causes in 1909 at the Pine Ridge Reservation, South Dakota.

Youth & Rise to Power

Red Cloud was born in 1822 on the banks of the Blue Water Creek near the Platte River in North Platte, Nebraska. His father, Lone Man, was a Brule chief of the Teton Sioux, and his mother, Walks-as-She-Thinks, was Oglala Sioux. Shortly before Red Cloud's birth, some of the people reported seeing a red streak, possibly a meteor, in the night sky and so Lone Man named his son Makhpiya-luta – Red Cloud – to appease the Great Spirit.

Lone Man died in 1825 from alcoholism after becoming addicted to the cheap whiskey white traders introduced to the Sioux, and Red Cloud and his mother were taken in by her brother, Chief Old Smoke. The boy was raised by his mother, by Old Smoke, and by his other uncle White Hawk. Drury and Clavin write:

White Hawk was responsible, along with Walks-as-She-Thinks, for the child's education and, before Red Cloud was two years old, both his mother and his uncle were interpreting for him the message to be found in every birdsong and the track of every animal, the significance of the eagle feather in a war bonnet, and the natural history of the tribe in relation to its surroundings. By the age of four he was sitting at council fires emulating the gravity of his elders. (64)

Red Cloud excelled at sports and, especially, childhood 'war games' similar to the popular 'King of the Hill', which were played at night and encouraged stealth and patience in attacking or defending a position. The boy was also the best at archery competitions and quickly mastered horseback riding after his uncle gave him a small colt. He joined his first war party when he was around 16 as a member of a raid on a Pawnee village to avenge the death of his cousin, recently killed by Pawnee warriors. Red Cloud was praised by the others in the band and honored for making his first kill and taking his first scalp from an enemy. Although Red Cloud was pleased with the honors, he understood that warriors were regarded more highly for counting coup than for killing an opponent.

The honor attached to counting coup is illustrated in the legend, The Sioux who Married the Crow Chief's Daughter, in which Chief Big Eagle goes into battle armed only with a coup stick and refuses to kill his opponents. It was a military tradition of touching an enemy – either with one's hand, a knife, spear, a coup stick or any other object – without killing him. In doing so, one dishonored one's enemy – who could as easily have been killed – while gaining distinction for skill and courage as one could just as easily have been killed oneself. Red Cloud's early achievements in childhood war games allowed for his later success in counting coup. Drury and Clavin comment:

By the time Red Cloud reached his late teens, his fighting qualities – reckless bravery, stealth, strength, and imperviousness to personal danger – had been established and were merely being honed and perfected. (77)

He became recognized as a ruthless warrior, able strategist, and powerful leader by the time he was 20. As he would later remark, "When I was young among our nation, I was poor. But from the wars with one nation or another, I raised myself to be a chief" (Drury & Clavin, 71). He became the leader of Old Smoke's band, known as the Bad Faces (so-called because of an incident in which the warrior Bull Bear threw dust into Old Smoke's face) and was an established chief by the time he was 30 years old. He married Pretty Owl (also known as Mary Good Road, l. 1835-1940) in 1850 and started a family.

Red Cloud's War

The Sioux had been expanding their territory for decades, fighting wars with the Crow, Kiowa, Pawnee, and Ute for hunting grounds, horses, to avenge an insult or death, or for personal or tribal honor. In 1820, a group of Lakota Sioux joined the Cheyenne war party in an attack on the Crow, known as the Tongue River Massacre, that devastated the Crow nation and won the Powder River region for the Cheyenne-Sioux alliance. Between 1820 and 1840, the Sioux expanded their territories further, taking more land from the Crow.

Beginning c. 1825, white settlers started arriving in the region, sometimes passing through to the west coast and other times establishing trading posts and staking claims to parcels of land. Initially, there were only small pockets of white settlers – such as the trading post of Fort William, established in 1835 – but by 1863 the Bozeman Trail was opened through Sioux land to allow settlers access to the gold fields further west.

According to the Fort Laramie Treaty of 1851, the Powder River territory belonged to the Crow – who were on good terms with the United States – but according to the Sioux, it was theirs through the established tradition of Native American warfare and conquest. Red Cloud and others opposed the influx of white settlers through their lands, and the US government responded with the Powder River Expedition of 1865, which was supposed to subdue the Sioux, Cheyenne, and Arapaho but failed to accomplish anything.

Red Cloud arrived at Fort Laramie in June 1866 to negotiate the withdrawal of white settlers from Sioux lands and the closing of the Bozeman Trail but found that Colonel Henry B. Carrington (l. 1824-1912) had been commissioned to build forts in the area to protect settlers using the trail from Native American attacks. Red Cloud left the meeting and organized his people for war. His natural charisma and reputation as a fearless warrior unified the diverse bands of Sioux and others who recognized him as the leader of this particular war party; this would later be misunderstood by Euro-American writers who characterized him as Chief of the Sioux.

The Sioux and their Cheyenne and Arapaho allies struck at the forts and wagon trains using guerilla tactics, especially targeting the civilians sent in groups from the forts to gather wood and hay. Horses at the forts were regularly stampeded and stolen and supply wagons intercepted. Attempts by US troops to engage with the Sioux were futile as, under Red Cloud's direction, they seemed to be able to strike anywhere, simultaneously, and then vanish into the prairie.

In December 1866, Captain William J. Fetterman (l. c. 1833-1866), under Carrington's command, led a force of 80 men to relieve an attack on a wood train a few miles outside the fort. Carrington ordered the captain to only break off the attack and return with the civilians and the wood, and specifically ordered him not to follow any Sioux warband beyond the Lodge Trail Ridge, which would take him too far from the fort for reinforcements to arrive quickly. Fetterman ignored these orders, was lured beyond the Lodge Trail Ridge by the young warrior Crazy Horse (l. c. 1840-1877), and all 81 troops were killed in the ambush known as the Fetterman Massacre, Battle of the Hundred-in-the-Hands, Fetterman Fight, or Battle of a Hundred Slain.

Red Cloud continued the guerilla war after this – with support from other Sioux leaders including Sitting Bull (l. c. 1837-1890) – and further engagements, such as the Hayfield Fight and the Wagon Box Fight (both in August 1867), show his continued practice of targeting civilians who supplied the forts with hay, wood, and other necessary items. Although these two engagements are the best-known, Red Cloud attacked and harassed the troops and civilian contractors in many others throughout 1867 and into 1868.

Treaty & Travels

By late summer of 1868, forts in the Powder River territory were abandoned and all troops were withdrawn to Fort Laramie for safety reasons while the government tried to bring Red Cloud to the negotiating table. Once the forts had been vacated, Red Cloud had them burned. In November 1868, he arrived at Fort Laramie to sign the treaty which established the Great Sioux Reservation and closed the Bozeman Trail.

The treaty made many promises – including allotments of clothing, the construction of various buildings, that no one would pass over or settle Sioux lands without their permission – but these and the many others were not kept. Red Cloud understood that the white man could not be trusted – something he seems to have learned in his youth – but had defeated them in combat and was sure they were aware he could do so again if he chose; so, he signed the treaty in the understanding that the defeated party had no choice but to honor it.

In 1870, he traveled to Washington, D.C. and met with President Grant and Ely S. Parker (l. 1828-1895), the Commissioner of Indian Affairs and a member of the Seneca nation. Red Cloud was shown the arsenals and military strength of the United States while Parker, and others, explained the benefits of the reservation system to him, encouraging his acceptance of this new mode of living. At this time, all the forts in the Powder River territory had been vacated and burned, no new settlers had arrived, and the Great Sioux Reservation was intact, so Red Cloud seems to have felt there was no need for concern. He also became aware of the seemingly endless numbers of white people who would move against him, along with their impressive weaponry, should he mount another resistance to them. He agreed to the establishment of the reservation known as the Red Cloud Agency and moved his people there by 1873.

In 1874, however, gold was discovered in the Black Hills – the region of the Great Sioux Reservation known to them as Paha Sapa – "The Heart of Everything That Is" – understood as the origin point for the Sioux Nation. The Fort Laramie Treaty of 1868 had promised the Black Hills to the Sioux forever, but this was ignored by the US government, and white settlers and prospectors began arriving in the region, staking claims to land, and setting up trading posts.

In 1875, Red Cloud and his delegation returned to Washington, D.C. to remind Grant of the treaty, but he was told the government had a new deal to offer: the Sioux would be given $25,000.00 for their land and be moved to Indian Territory (modern-day Oklahoma). Red Cloud refused to continue the talks and Grant had him hurried out of Washington and sent to New York City where, as scholar Adele Nozedar observes, they hoped "he would be dazzled by the world of the white man" (400). Nozedar continues:

Red Cloud, unimpressed, used the opportunity to address a large number of people. Here, he explained in simple terms precisely what had happened, demonstrating a gift for oratory which would mark him in the history books as a great statesman:

"In 1868, men came out and brought papers. We could not read them, and they did not tell us what was in them. We thought the treaty was to remove the forts and that we should then cease from fighting…When I reached Washington, the Great Father [the president] explained to me what the treaty was and showed me that the interpreters had deceived me. All I want is right and just. I wish to know why Commissioners are sent out to us who do nothing but rob us and get riches of this world away from us." (402)

Red Cloud's eloquence did nothing to change government policy, however, and he returned to the agency land he had been promised – which was then moved three times before it was established in South Dakota and became the Pine Ridge Reservation. His travels to the east had convinced him that he could not win a prolonged war against the white man, as their numbers were too great and weapons too powerful, and that, no matter what they promised, it was all lies. As he put it, "The white man made me a lot of promises and they only kept one. They promised to take my land, and they took it" (Drury & Clavin, 351).

Conclusion

When Crazy Horse and Sitting Bull – who had denounced the Fort Laramie Treaty of 1868 – mounted the resistance known as the Great Sioux War of 1876-1877, Red Cloud refused to join them and also opposed the Ghost Dance movement of 1889. Believing that any further military engagement with the United States was futile, Red Cloud devoted himself to negotiations and legal actions to improve the lives of his people on the reservations.

He became friends with several white people who advocated for his cause, including the paleontologist Othniel C. Marsh (l. 1831-1899) and the Indian Agent and surgeon Valentine McGillycuddy (l. 1849-1939). In 1884, Red Cloud, Pretty Owl, and their children converted to Christianity and became Catholics as part of his ongoing attempt at living peacefully with the white settlers who now held his former lands outside the reservation.

As a statesman, he became the voice of his people during his visits to the east as well as through interviews given and his unfinished autobiography. He continued to advocate for the rights of the Plains Indians generally and the Sioux specifically until his death on 10 December 1909. His son, Jackson Red Cloud (l. c. 1858-1918), then took over as chief of the Oglala Lakota Sioux and his descendants have maintained that position up through the present era. Pretty Owl outlived her husband for over 30 years and is buried next to him in the Holy Rosary Cemetery of the Pine Ridge Reservation.

Red Cloud outlived Crazy Horse, Sitting Bull, and the other leaders who had continued the fight to defend their land, choosing to use the white people's own legal system to advance his cause rather than violence. He consistently fought for the return of the Black Hills to his people, and as of this present date, the Sioux are continuing his fight with the US government, which is still refusing to respect their claims. In August 1987, the US Postal Service issued a ten-cent postage stamp in Red Cloud's honor; and that is the only honor any agency associated with the US government has ever paid him.