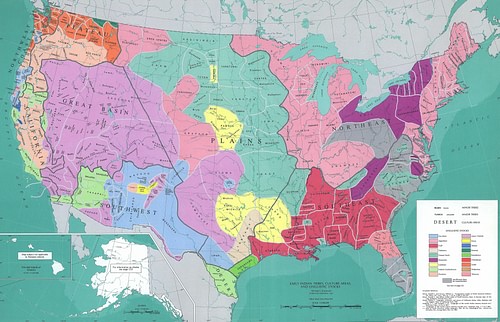

The Plains Indians (also known as Native Americans of the Plains and Prairie, Indigenous Peoples of the Great Plains) are the original inhabitants of the western plains of North America, now part of the United States and Canada. They are the Native Americans most often depicted in media from the 19th century to the present.

The people of the plains had lived in the region for around 13,000 years and were originally hunter-gatherers following the seasonal migrations of bison until c. 700/900 CE when maize (corn) cultivation was introduced from Mesoamerica. Afterwards, they became semi-nomadic, establishing permanent, agricultural settlements while continuing to hunt game, primarily bison. Their culture was (and is) informed by their spiritual beliefs, which holds all life to be sacred, interconnected, and animated by elemental spirits. The religious beliefs of the different nations and tribes differ, but all believe in a supreme being or beings that created and maintained the world. Rituals including the Sun Dance, Ghost Dance, and Green Corn Ceremony were observed to honor the Great Spirit, renew the earth, and revitalize the community.

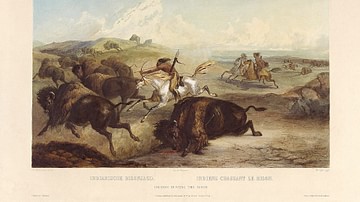

Horses represented a nation's military and political power, best attested by the rise of the Comanche who used the horse to establish themselves as the most powerful Native American tribe. Indigenous peoples hunted and traveled on foot until the 16th century when the horse was introduced to North America by the Spaniards, and was already a valued commodity to the Native peoples before the Pueblo Revolt of 1680, as they increased a tribe's mobility and allowed for the development of the mounted warrior. After the 1680 revolt, which released thousands of horses into the wild, they signaled a Native American Nation's status even more - as there were more horses available - exemplified by the Comanche who, through mastery of the horse, became the "Lords of the Plains." The horse expanded a tribe's hunting territory and encouraged some to "leave the corn" and return to a hunter-gatherer societal model.

Contact with Europeans beginning in the 16th century brought diseases that greatly reduced the population of the Plains Indians, and their numbers were reduced further by military campaigns by the United States Army, especially during the 19th century. The most famous victory of the indigenous tribes over the United States' forces was the Battle of Little Bighorn in 1876, fought by a coalition headed by Lakota Sioux and Cheyenne. There was no stopping the advance of white settlers and their government, however, and the last formal resistance was crushed through the Wounded Knee Massacre on 29 December 1890. Afterwards, the tribes were relegated to reservations and became dependent on commercial transactions with white settlers for their livelihood.

Region & Nations

The Plains Indians are a diverse group of territorial nations, each with a distinct culture. Generally speaking, all the different nations were on equal footing until the arrival of the Europeans and the introduction of the horse and firearms. Scholar Michael G. Johnson describes the region and general cultural characteristics:

Of all North American Indians, the former native inhabitants of the Prairies and Plains are the most popularly and widely known. Their area ranged from the Mississippi valley in the east to the Rocky Mountains of the west, and all the way from the Saskatchewan River in the north to the Rio Grande in the south. The western High Plains are very arid and are marked off by their short grass vegetation. The east, with a higher level of precipitation, is the Prairie, characterized by its dark soil and tall grass. The whole area was once home to teeming game, bison, pronghorn antelopes, wolves, coyotes, deer, and bears. The main river systems run west to east to link to the Missouri and the Mississippi along which forested patches were found. The cultural traits that came to characterize the High Plains peoples were dependence on the bison (buffalo), limited use of roots and berries, limited fishing, absence of agriculture in the High Plains, use of the tipi (teepee), skillful use of bison and deer skins, rawhide, geometric art, and the travois. Social characteristics included camp circle organization, division into bands, and men's societies. Religious traits included the Sun Dance, sweat lodge and vision quest observances, and scalp dances. (92)

The main language families of the nations are Algonquin (Algonkian), Caddoan, Siouan, and Uto-Aztecan. The specific nations, listed here according to language family, included:

Algonquin:

- Arapaho

- Blackfoot

- Cheyenne

- Cree (Plains Cree)

- Gros Ventre (Atsina)

- Ojibwa (Plains Ojibwa)

- Sarsi (Athabascan)

Caddoan:

- Kichai

- Kiowa

- Pawnee

- Shuman

- Tawakoni

- Waco

- Wichita

Siouan:

- Arikara

- Crow

- Dakota & Lakota Sioux

- Mdewakanton Sioux

- Sisseton Sioux

- Teton Sioux

- Wahpekute Sioux

- Wahpeton Sioux

- Yankton Sioux

- Yanktonai Sioux

- Hidatsa (Minitaree)

- Iowa

- Kansas

- Mandan

- Missouri

- Omaha

- Osage

- Oto

- Ponca

- Quapaw

Uto-Aztecan:

- Comanche

- Padouca

The culture of each of the above is informed by their spiritual beliefs which, among other aspects, emphasizes the uniqueness of one's tribal nation, the importance of valuing the community over one's individual needs, and the observance of rituals thanking the gods, spirits, and earth for their gifts and unifying the people with a collective understanding of the world and their place in it.

Religion & Sun Dance

As noted, each nation holds to its own beliefs, but all understand they have been created and placed on the earth in a specific region by a higher power who expects them to recognize and respect all life and to give back in gratitude for all of the gifts that are given. All land is considered sacred, but one's own land especially so, as it is understood to be the place of one's origin. Scholar Larry J. Zimmerman notes:

At the core of each Native culture is an abiding reverence for the region in which the people live. The terrain there is sacred, a source of identity and strength. In the Southwest, the Hopi believe that they emerged at the confluence of the Colorado and the Little Colorado rivers, and the Tewa say that their ancestral territory is enclosed by four sacred mountains. This topographical pattern is repeated across the regions – and it is one reason why forced relocation was so culturally destructive. (155)

As the land provides one with vitality and identity, one is expected to care for and give back to it not only through one's daily life but also through ritual observances. The most important of these for the Plains Indians is the Sun Dance, which has different meanings to different nations, but, basically, is enacted to reawaken the earth after the sleep of winter and give thanks for the life-giving sun.

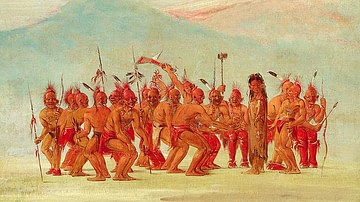

A Sun Dance could be initiated by a man or woman who had either received a vision directing them to, as an offering in hopes of receiving something one has prayed for, in thanks for an answered prayer, or as an offering for the welfare and prosperity of one's community. It was (and now is) usually observed in June and involved the entire village. A temporary lodge was constructed with a pole at the center topped by the head of a buffalo killed by a single shot. Leather thongs were attached to the top of the pole and the other ends would later be threaded through the shoulders or pectorals of fasting participants who wished to prove their courage or redeem a fault, but, usually, in hopes of receiving a vision which would give them direction in life and enable them to give back to the community, the land, and the spiritual forces. The pain and physical exhaustion of this ritual, or through continuous dance, was understood as a necessary offering to receive a vision, awaken the earth, and give thanks to the spirits. Scholars Margot Edmonds and Ella Clark, quoting from the story, Hidatsa Sun Dance Ritual, describe the ceremony as observed by the Hidatsa after it had been announced and the people gathered:

Medicine-men arranged themselves south of the entrance to the Sun-Lodge. The old women of the tribe who prepared the spot for the Sun Dance, together with the medicine-women, sat on the north side. All come to pray and to fast. The relatives of the young male Fasters entered, carrying food. Each Faster took a bowlful of the food to a clansman of his father. Then came the challenge to the Fasters' bravery. They approached the Priest and the Singer. Two small slits were cut in the shoulder skin, a leather thong was threaded with a wooden pin attached to the end, preventing the thong from pulling out of the slotted skin.

The other ends of these thongs were attached to the top of the sun-pole (similar to a Maypole). The Priest and Singer twirled each Faster four times, his feet barely touching the ground, Then the Faster swung free, twisting and circling around the sun-pole. But he dared not touch the thong with his hands…When the Faster finally broke loose from the sun-pole, he fell to the ground. Priest and Singer placed him gently on his bed of healing sage. There he remained and fasted from two to four days…The young Fasters lay upon their beds of sage. They have dreams and visions which they relate to the Priest. If they were sufficient, the Faster left the Sun-Lodge because his supplications were answered by the Sun-God. (197-198)

The ritual also involved dancing, non-stop, for two to four days – also in hopes of receiving a vision – and the practice involving the thongs was not always observed. The Sun Dance of the Cheyenne, for example, focused wholly on reawakening the earth through music and dance while thanking the Great Spirit for life and the gifts of the land and did not usually involve the self-torture of the Sioux ritual.

Daily Life, Government, & Warfare

There is not a single Great Spirit known by the same name venerated by the people of every nation, but each understands their supreme being in similar ways. There are also many other spirits to be acknowledged and thanked through ritual, sacrifice, and prayer, and entities one needs to be wary of. Coyote, a trickster-god figure, might be helpful or hurtful depending on his mood, while Old Woman Who Never Dies – a corn spirit/agricultural goddess – could be counted on for her kindness and the gifts of the harvest. Old Woman Who Never Dies is identified with various natural and supernatural aspects of life by different nations and was sometimes a healer, bestowed the power of prophecy or gave prophecies, was the moon in all phases, and granted visions. Old women are frequently featured in the lore of the Plains Indians as in the tale of the origin of the buffalo who were brought to the Plains by an old woman who guarded a mystical portal in a cave.

These spirits inform one's daily life which one is expected to live with reverence. The Hidatsa celebrated the Corn Ceremony in spring or early summer in honor of Old Woman Who Never Dies, but she was understood to be present in everything one does every day. Scholar Jeffrey Ostler comments on the daily life of the Plains Indians:

Women planted corn they had bred to mature rapidly in the perilously short growing season of the northern Plains. Prior to planting, women performed public rituals that honored Old Woman Who Never Dies and enlisted her aid. When the geese Old Woman Who Never Dies annually sent up the river arrived (around May), women performed planting ceremonies, sometimes asking a male corn chief to bless the seed. Throughout the growing season, women labored in care of their corn and other crops (beans, sunflowers, squash), all the while relying on Old Woman Who Never Dies. Because villagers also depended on buffalo, men performed buffalo calling ceremonies throughout the year to enable successful hunts on the surrounding grasslands. (Hoxie, 235)

The spirits were understood to hear these prayers and answer these calls by sending the buffalo and providing abundant harvests. Clothing was made primarily of buffalo or deer hide as was footwear, while tools, knives, cups, chest armor, and other items were made from the bones. Crops included the Three Sisters (corn, squash, beans), sunflowers, plums, and tobacco which was considered sacred and often used in rituals. Women tended these crops, made the clothing and moccasins, stitched and erected the teepees, and were understood as the owners of the teepee or permanent home and almost everything within it.

Twelve Stories of the Plains Indians

Women could divorce a husband who displeased her by throwing his belongings out of the residence, and he was then homeless unless taken in by relatives. Women kept custody of any children from the union, tended to all aspects of the home, including preparing food, and raised the children until the boys were old enough to go on hunts with their fathers; men did the hunting, protected the village and hunting grounds, maintained the living quarters and communal area of the village, and also protected – or enlarged – their territory through warfare.

War was declared after an assembly was called of the elders of the nation and most prestigious warriors by the chief. The government of the Plains Indians, generally, was similar to the Sioux who chose their leaders based on exemplary conduct (especially demonstrations of courage and wisdom) or on their family name. The assembly would convene to make decisions on any matter of importance to the community but, overall, each individual family and extended family understood their responsibilities to everyone else and performed them without any kind of enforcement by an authoritative body.

How or why warfare was conducted before the 16th century is unclear but, based on what is known of other Native American nations, it would have involved a band of warriors attacking another tribe for captives that could then be ransomed back or kept as slaves, to punish others for some crime against one's people, or for prestige. After European contact, wars were fought between native nations for control of the lucrative fur trade, for horses, to prevent another tribe from trading with the Europeans, for guns and ammunition, and to protect one's land and resources.

After the arrival of the horse, the Comanche became the most powerful nation of the Plains and Prairies through their masterful horsemanship and ruthless tactics. Comanche raided the villages of other indigenous tribes and European settlements regularly, becoming the most powerful and feared nation of the Plains until they lost almost half their population to European diseases like smallpox in the 19th century and were then defeated in battle by the US Army, losing their land to the steady influx of white American settlers like all the other nations also had.

Conclusion

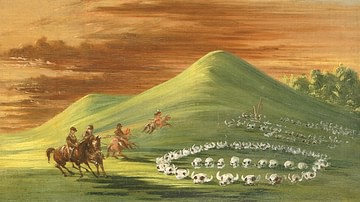

The influx of immigrants in the east, and the need for more land for the cultivation of crops like cotton, resulted in United States governmental policies that evicted the native peoples of that region from their land and relocated them westward, pushing other nations further west and then further, uprooting the Plains Indians from their ancestral territories. Agreements in the form of treaties between Native Nations and the US government were routinely made only to be broken when the government wanted more land in pursuing the doctrine of Manifest Destiny, which claimed the United States had the right to the land north of Mexico and south of Canada from coast to coast. The Plains Indians that survived outbreaks of disease, military campaigns, purposeful slaughter of the bison to deprive them of their major resource, forced deportation, or random attacks by settlers were moved onto reservations. Ostler notes:

The idea was that these tribes could make a transition to "civilization" through farming, but without hunting to supplement growing crops, these groups had a hard time supporting themselves, sometimes clashing with other tribes and beginning to fall into poverty. Alcohol, material deprivation, disease (smallpox and cholera), and violence combined to reduce the Otoe-Missouria population from 1200 in the 1820's to 600 in the 1850's. While disease ate away at these people, it devastated the Mandan, Arikara, and Hidatsa in 1837, when smallpox arrived on a trading company steamship. These tribes had seen a modest increase in their populations over the generations since smallpox hit in the 1780's, but the 1837 epidemic was even more crushing. It carried a mortality rate between 70 and 90 percent. Overall, the Mandans, with a population of 9000 in the 1750's, had been reduced to only 150 in 1838. (Hoxie, 241)

The Wounded Knee Massacre of 1890, resulting in the deaths of over 250 Lakota Sioux men, women, and children, ended the so-called Indian Wars of the 19th century, but the policies of the United States government continued to limit or deprive the indigenous peoples of the most basic necessities, apparently in the hope they would quietly disappear. Their descendants still live in the region, however, and are presently engaged in legal battles for the return of their land. In 1990, the United States Congress passed a resolution apologizing for the Wounded Knee Massacre and expressing their regrets, but, as of 2023, have yet to fully address the many other injustices visited on the Plains Indians.