The buffalo were essential to the Plains Indians, and other Native American nations, as they were not only a vital food source but were regarded as a sacred gift the Creator had provided especially for the people. Buffalo (bison) supplied Native Americans with the resources that sustained them physically, culturally, and spiritually.

Among Plains Indian nations including the Sioux, Cheyenne, Arapaho, Blackfoot, Pawnee, Kiowa, Mandan, and Comanche – as well as over 20 others – the American bison (commonly referred to as buffalo) was essential to every aspect of their daily lives, and today it is still honored by these nations in the same way. Commenting on the importance of the buffalo to Native Americans, historian Richard B. Williams notes:

The American Indian and the buffalo coexisted in a rare balance between nature and man. The American Indian developed a close, spiritual relationship with the buffalo. The sacred buffalo became an integral part of the religion of the Plains Indian. Furthermore, the diet of primarily buffalo created a unique physiological relationship. The adage, "You are what you eat" was never more applicable than in the symbiotic relationship between the buffalo and the Plains Indian. The Plains Indian culture was intrinsic with the buffalo culture. The two cultures could not be separated without mutual destruction. (Hunter, 3)

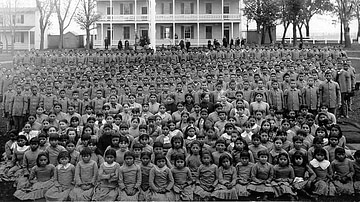

Between c. 1840-1890, with the approval and encouragement of the US government, millions of buffalo were slaughtered primarily to deprive the Plains Indians of their major resource and allow for the westward expansion of Euro-American settlements. The large herds of buffalo, and the nomadic Plains Indians, impeded initiatives such as the transcontinental railroad and so were regarded as obstacles to be eliminated. White buffalo hunters, US military, merchants, and white settlers all engaged in the systematic slaughter of the buffalo to deprive the Plains Indian nations of their livelihood and drive them, along with the buffalo, to extinction.

At the height of the Plains Indians culture, there were over 60 million buffalo in the region now known as the United States, but by 1900, there were less than 300 (no more than 1,000) due primarily to the orchestrated slaughter of the animals by the US government and east coast business concerns to eradicate the Plains Indians or, at least, to "manage" them on reservations. Both the buffalo and the Plains Indians nations survived, however, and today these nations and others work constantly to repopulate their regions with buffalo herds.

Origin Tales & Rituals

Every Plains Indian nation has an origin story concerning the buffalo, and in each one, the animal is recognized as a sacred gift from the Creator. Cheyenne legends of the buffalo relate how the first herd was given to the people by the supernatural savior figure of Grandmother (who appears in many stories concerning the gifts of the spirit world) after a show of exceptional bravery by three Cheyenne hunters in entering a mysterious cave. In the Cheyenne story Falling Star, the hero Hotoketana'ohtse ("Falling Star") provides the people with buffalo after tricking and defeating the spirit-bird, who always warned the herds away from the seasonal hunt.

Although the Plains Indians regularly hunted the buffalo, they honored the animal as a close relation who generously gave of itself for their survival. There are many stories concerning the buffalo from all different nations highlighting this relationship as well as the rituals that developed from the spiritual connection between the people and the buffalo. The Mandan Buffalo Dance is one such ritual – still performed today – but the best-known is probably the Sun Dance, observed by many different nations, in which the skull of the buffalo features prominently, and the spirit of the animal informs the ceremony.

Famous figures such as White Buffalo Calf Woman embody this spirit of generosity as she is understood by the Sioux as an intermediary who gave the people the rituals necessary for communing with the Great Mystery, the Creator God. After giving the people the seven sacred rites of the Lakota Sioux, White Buffalo Calf Woman departed, but, as she left, she transformed into her true form of a buffalo. To the Sioux, the buffalo was therefore this intercessor between them and the spirit world. The Sioux legend, The Mysterious Butte, shares similarities with the Cheyenne legends and those of others in having the arrival of the buffalo prophesied by images appearing outside a chamber of the butte.

The Pawnee origin story, Making the Sacred Bundle, relates how the buffalo were responsible for the development of the medicine bag and the sacred objects one carries for protection, spiritual strength, and guidance. One of the most popular Pawnee stories is The Girl Who Was the Ring, featuring a herd of buffalo who enjoy playing the game of chunkey and magically transform a young girl into the ring used in the game. Chunkey was played as a sport but also to resolve conflicts between individuals and as a spiritual ritual, and so it is no surprise to find a story about the game in which the buffalo figure so prominently, as these animals were integral to the existence of the Plains Indians nations on every level.

Plains Indians & the Buffalo

Before the arrival of the horse in the region, and for some nations even afterwards until they had mastered horsemanship, buffalo was hunted on foot. Each nation had its own rituals prior to the hunt and stories concerning these events, but generally speaking, buffalo were usually driven over cliffs, onto frozen bodies of water, or into enclosures – either manufactured or natural – where they would be killed. Scholar Adele Nozedar comments:

Hunting the buffalo must have been a feat of endurance, agility, and strength; the buffalo, despite its lumbering appearance, is in fact built for speed, and can run up to 37 mph [60 km/h], is able to leap vertically to a height of 6 feet [1.8 m] and is infamously bad-tempered. Prior to the coming of the horse, buffalo were "captured" by being herded into narrow "chutes" made of brushwood and rocks; they were then stampeded over clifftops in areas called "buffalo jumps." It would take large groups of people to herd the animals, often over several miles, until the stampede was big enough and fast enough to run head-first over the precipice. Such a method of killing meant that there was usually a massive surplus of meat, materials, bones, etc. (64)

The surplus was preserved for lean times or traded with others. Every part of the animal was used, and nothing was wasted, because it was understood that the buffalo were giving themselves willingly to the people as a gift, and that gift should be fully appreciated. Nozedar comments on the uses the people made of the buffalo:

The list of uses to which the animal was put is impressive. The hides provided bedding, clothing, shoes, and the "walls" of tipis. The meat was good, nutritious food. The bones and teeth were used to make tools and also sacred implements. The hooves of the animal could be rendered into glue. Horns made cups, ladles, and spoons. Even the tail of the buffalo made a fly whip. The bones could be used to scrape the skin to soften it and was also fashioned into needles and other tools. Some tribes used the bone to make bows.

The buffalo provided leather and sinewy "string" for those bows. Even the fibrous dung was used to make fires. The rawhide, heated by fire, thickened; this material was so tough that arrows, and sometimes even bullets, couldn't penetrate it, so it made an effective shield. This rawhide was used to make all manner of objects: moccasin soles, waterproof containers, stirrups, saddles, rattles, and drums for ceremonial purposes, and rope. Rope could also be made from the hair of the buffalo, woven into tough lengths. Even boats were made from buffalo hide, stretched across wooden frameworks. (62)

The rawhide was also sometimes fashioned into the ring used in playing chunkey among those nations that did not use a discoidal stone for the game. In chunkey, the sticks one threw at the rolling rawhide disc or stone were individually marked so that each player's score could be tallied accurately, and in this same way, once Native Americans began hunting buffalo on horseback, the arrows and spears used were clearly marked so the hunter would get credit for his kill.

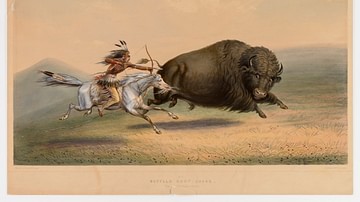

After the horse, hunting parties would chase the herd, once it had been located, and kill the animals with a single arrow shot or thrust with a spear or lance. A well-placed shot, at the right moment, could go through one buffalo and into another or even a third, and this was recognized as a great feat and worthy of honor and stories told later about the hunt. After European firearms were introduced to the region, the same paradigm was adhered to in that a hunter was expected to bring down a buffalo with a single shot from a rifle, but, of course, there was no way of marking bullets.

The horse and European firearms changed the traditional buffalo hunt in many other ways. The horse expanded the reach of the individual nations into broader hunting grounds on the Great Plains, bringing them into conflict with each other over resources. Horses came to represent a nation's economic and military strength, and so raids to steal horses became increasingly common, but these raids also served to keep a nation's enemies from the buffalo.

The Sioux, to cite only one example, attacked the Pawnee, Arikara, Mandan, and Hidatsa, among others, destroying villages, killing people, and taking horses, in part, to deprive them of access to the buffalo. Firearms, especially those of the mid-19th century, increased a single warrior's range and killing power. The conflicts between the Plains Nations over hunting grounds and rights of access were overshadowed, however, by the 19th-century initiative of white settlers, businessmen, and politicians to "tame the wild Indian" and "advance civilization" all the way to the Pacific Ocean.

Buffalo Slaughter of the 19th Century

The transcontinental railroad, the discovery of precious metals like gold on Native American land, and the press of settlers to claim large tracts of land in the west for cattle-rearing encouraged the policy of the US government to eliminate the buffalo as a means of subjugating the Plains Indians. Beginning as early as 1820, but increasing in frequency from c. 1840 on, more and more buffalo were killed by white hunters for sport, hides, tongues, or for no reason at all.

Some of the treaties signed between representatives of the US government and the tribal nations, such as the Sioux, stipulated the indigenous people held rights to the lands on which they hunted buffalo. If the buffalo were eliminated, so were the rights of the people to the land. Scholar Pekka Hamalainen writes:

The U.S. government was determined to subjugate the Lakota…knowing that Indigenous sovereignty in the plains rested on the bison, Secretary of the Interior Columbus Delano welcomed the destruction as a way to accelerate the nomads' domestication, and army officers provided protection and ammunition to hunting squads. Between 1872 and 1874 white hunters may have shipped more than three million hides to the East from the southern and central plains – close to three thousand animals per day – plunging the herds into a terminal decline. (345)

As the buffalo began to vanish, the Plains Indian nations suffered starvation as well as the lack of all the resources the buffalo had always provided. The slaughter of the buffalo also served to demoralize the Indigenous Nations as they witnessed the meaningless destruction of the animal they regarded not only as a close relative and provider but also as an intermediary between them and the Creator. Scholar Roxanne Dunbar Ortiz cites Old Lady Horse of the Kiowa in describing the process of the white hunters, which was nothing like that of the Plains Indians:

Then the white men hired hunters to do nothing but kill the buffalo. Up and down the plains those men ranged, shooting sometimes as many as a hundred buffalo a day. Behind them came the skinners with their wagons. They piled the hides and bones into the wagons until they were full and then took their loads to the new railroad stations that were being built to be shipped east to the market. Sometimes there would be a pile of bones as high as a man, stretching a mile along the railroad track. The buffalo saw that their day was over. They could protect their people no longer. (143)

Some of the hunters who had participated in the mass slaughter of the buffalo came to realize the enormity of the crime and advocated for preservation and protection, among them the famous Buffalo Bill Cody (l. 1846-1917), who had killed thousands of the animals, but the US government was more interested in the subjugation and control of the Native population. In 1874, with the buffalo nearing extinction, Congress proposed a bill to protect the animal, but it was vetoed by President Ulysses S. Grant, and the slaughter continued.

Conclusion

Efforts to save the buffalo from extinction were spearheaded in the East by the conservationist and zoologist William Temple Hornaday (l. 1854-1937), best known as the first director of the New York Zoological Society Park (today's Bronx Zoo), who founded the American Bison Society for this purpose in 1905. Hornaday was able to win the support of President Theodore Roosevelt, who, although he had little sympathy for Native Americans or what the buffalo meant to them, was an ardent conservationist.

Hornaday began his initiative in 1887, but before this, a rancher named Fred Dupree (l. 1818-1898) had already launched his own efforts out west in South Dakota. Dupree's wife, Good Elk Woman (also known as Mary Ann Dupree) was Lakota Sioux and encouraged him to save the buffalo. In 1883, Dupree and his sons caught five buffalo calves and began to breed them on his ranch. These five had become 80 by the time of Dupree's death in 1898, and, afterwards, they were purchased by another rancher, James "Scotty" Philip (l. 1858-1911). Author Steve Nelson comments:

Philip's attitude toward the buffalo, like Dupree's, was influenced by his Lakota wife, Sally. When Frederick Dupree passed away in 1898, Philip bought his buffalo. He placed the animals on a riverside ranch, just north of Fort Pierre, where they thrived. By 1911, when Philip died suddenly, the herd numbered almost 900 animals. No buyer was willing or able to take the whole herd, so it was dispersed. Among the buyers was the state of South Dakota, which placed 36 buffalo in the newly established Custer State Park. That herd, in turn, was used to stock other parks and refuges around the country. (2)

Today there are between 30,000-50,000 bison in North America, far more counting those in reserves, that came from Fred Dupree's and Scotty Philip's starter herd. Initiatives by many Plains Indian nations, including the Blackfoot, Sioux, Cheyenne and Arapaho, Pawnee, and Comanche continue to preserve and reintroduce buffalo to the reservations. Conservation groups like the Tanka Fund and individuals like author Dan O'Brien and his wife Jill also work to preserve the buffalo and increase its numbers.

Ironically, the US government, primarily responsible for the animal's near extinction, declared the buffalo the national mammal of the United States in 2016. The North American bison herds continue to increase, and it is no longer regarded as an endangered species; good news to the Native American nations who regularly welcome the return of the buffalo to their lands.