Chunkey (tchung-kee) is a Native American game involving a rolling disc (or ring) and two teams of players who score by throwing their sticks to land as close to the disc as possible. The game is thought to have originated at Cahokia c. 600 CE, was popular among many Native nations, and is still played today.

The game is also known as chenco, chungke, chunky, tchungkee, hoop and stick game, and hoop and pole game. It was played, not only for entertainment but also to improve eye-hand coordination, dexterity, and stamina, to encourage the value of teamwork, and was also held by some nations to have spiritual significance. Although the earliest evidence of the game comes from excavations at Cahokia, it is possible it was played earlier and at different locations. According to the Cheyenne story, The Life and Death of Sweet Medicine, the game was created by their prophet and law-giver, Sweet Medicine.

By the 19th century, when the game was recorded by white settlers, it was being played by Native nations across North America. Evidence suggests the game traveled south where it was also played by the Aztecs. Spectators are said to have regularly gambled on the outcome of the game, even to the extent of staking themselves in the bet and losing their freedom to the winner.

The game’s popularity waned in the early 20th century but has experienced a revival. Native American groups in the present day continue the traditional game, teach it to their communities, and offer demonstrations to others. The game presently serves the same purpose as it did in the past while also connecting the people with their heritage.

Name & Origin

The name may mean "uncountable" or "immeasurable" as there was no way of knowing how far the disc would roll or where it would come to rest. Players seem to have made their calculations on where to throw their spears (or tchung-kee sticks) based on how the disc wobbled or slowed before stopping, but there was no way of knowing when it would actually land.

Archaeologists suggest Cahokia (in modern-day Illinois) as the game’s place of origin based on chunkey stones found in a grave at Mound 72 of the site. Cahokia as the point of origin would make sense as the city, which flourished between c. 600 and c. 1350 CE, was once the largest urban center in North America with long-distance trade routes stretching in every direction. The game would have traveled along these routes to many different destinations, accounting for the number of different nations that eventually adopted it as a favorite pastime and, in some cases, as a spiritual or religious ritual. Scholar Larry J. Zimmerman writes:

Sometimes sacred societies specialized in playing a particular sport. Team games certainly functioned as recreational activities, but like most aspects of Native life, they also served a broader social and religious purpose. The most widespread example of such a sport is the hoop and pole game. Played across the entire continent, the game was for men only and consisted basically of throwing a spear or shooting or throwing an arrow at a hoop or ring as it rolled along the ground. The hoop in particular possessed symbolic significance. In the Southwest, the Zuni version of the game used a hoop strung with netting that symbolized the web of an ancestral protector being called Spider Woman.

The game was of great antiquity and there was remarkable diversity in both the implements used and the rules of play. The number of players varied, but there always seem to have been two teams, perhaps representing some fundamental duality such as "we" (the people) and "they" (the unseen forces). When gambling was involved, as with the Arapaho, the takings were redistributed among team members. The timing of the matches was sometimes significant. For example, the Wasco near the Columbia River played the game to mark the first salmon run of the season. (99)

The game may have been played much earlier than c. 600 CE, however, as the builders and original inhabitants of the city are understood as the people of the Mississippian Culture (c. 1100-1540 CE) but two separate peoples recognized as preceding them (and often included with them) are the Adena Culture and Hopewell Culture, dated, respectively, to c. 800 BCE to 1 CE and c. 100 BCE to 500 CE. It is probable that the game was played by these people long before Cahokia and its playing fields were constructed.

Descriptions of Game

There is no record of how the game was played prior to European colonization of North America. The famous Chunkey Player Effigy Pipe found at Muskogee, Oklahoma, dated to 1100-1200 CE and thought to have originated at Cahokia, shows a kneeling man holding a chunkey stone in his right hand and chunkey sticks in his left, clearly suggesting the same aspects of the game as noted by white settlers later but giving no indication of whether the game was played in the same way.

Sergeant John Ordway (l. c. 1775 to c. 1817) of the Lewis and Clark Expedition recorded a game of chunkey as played by the Mandan on 15 December 1804. The spelling of the following account has been standardized according to modern English:

Although the day was cold and stormy, we saw several of the chiefs and warriors were out at play…they had a place fixed across their green from the head chief’s house, about 50 yards to the two chiefs’ lodge, which was smooth as a house floor. They had a battery [wall] fixed for the rings to stop against. Two men would run at a time with each a stick, and one carried a ring. They run about halfway and then slide their sticks after the ring. They had marks made for the game, but I do not understand how they count the game. (Discover Lewis & Clark, 1)

The best-known description of Mandan chunkey (as well as the earliest imagery) comes from artist and writer George Catlin (l. 1796-1872) in his letters of 1841:

This game is a very difficult one to describe, as to give an exact idea of it, unless one can see it played. It is a game of great beauty and fine bodily exercise and these people become excessively fascinated with it; often gambling away everything they possess, and even sometimes, when everything else was gone, have been known to stake their liberty upon the issue of these games, offering themselves as slaves to their opponents in case they get beaten. (Discover Lewis & Clark, 1)

The game of Tchung-kee [is] a beautiful athletic exercise which [the Mandan] seem to be almost unceasingly practicing whilst the weather is fair, and they have nothing else of moment to demand their attention. This game is decidedly their favorite amusement and is played near to the village on a pavement of clay which has been used for that purpose until it has become smooth and hard as a floor…

The play commences with two (one from each party), who start off upon a trot, abreast of each other, and one of them rolls in advance of them, on the pavement, a little ring of two or three inches in diameter, cut out of a stone; and each one follows it up with his `tchung-kee’ (a stick of six feet in length, with little bits of leather projecting from its sides of an inch or more in length), which he throws before him as he runs, sliding it along upon the ground after the ring, endeavoring to place it in such a position when it stops, that the ring may fall upon it, and receive one of the little projections of leather through it. (American Art, Tchung-kee, 1)

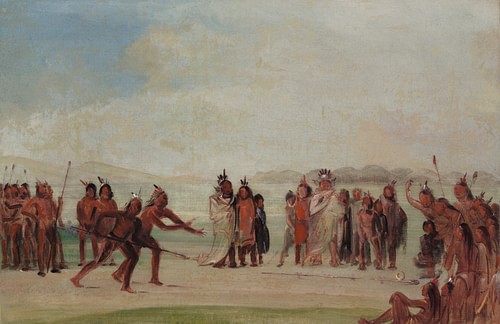

Catlin also sketched the game and illustrated it through his painting Tchung-kee, a Mandan Game Played with a Ring and Pole (see above). Both sketch and painting depict the same scene of two players, one of whom has thrown his stick, backed by their teammates and semi-surrounded by spectators. Catlin’s descriptions and imagery establish this as the same game witnessed in 1804 by Sergeant Ordway.

Play & Paraphernalia

It is unclear how long a given game was played, but points were scored by the player whose stick landed closest to the disc (or ring) and the team with the most points at the end were the winners. According to some sources, the game was played up to twelve points, however long that took. It seems players could throw their sticks in such a way as to change the course of the rolling disc at a moment, just before it seemed to be stopping, when their opponent was about to throw their own, thereby losing a chance at scoring but preventing a score for the opposing team. This may have been done when a player was up against an especially skilled opponent, but this is speculative.

The skill of the player who set the disc rolling would have also factored into how a given round of the game was played as, no doubt, some would have thrown the disc more effectively than others. A player would, therefore, have to take into account the skill sets of both the one rolling the disc and the opponent throwing the stick as well as the weight of the chunkey stone and how far it was likely to roll.

There does not seem to have been a standard size for the stone nor a standard material as stones have been found of varying sizes that were carved from limestone, quartzite, sandstone, or made of clay. The anthropologist George Bird Grinnell (l.1849-1938) describes a chunkey "stone" made of buffalo rawhide. The sticks were made of wood, but there does not seem to have been any standard regarding what kind or of any given weight, though the sticks seem to have been light.

Sticks were usually around six feet (1.8 m) long with one end pointed, decorated with leather, as Catlin describes, or with painted notches or other decorations. Some sources claim the sticks were notched to indicate points scored in a game and how much each point counted. Each team had its own colors or markings on their sticks as illustrated in the Catlin painting where the one player’s stick is white, and the other’s is black, and the ornamentation also appears to be different. This would only make sense as one would need to be able to make sure one could identify the player’s stick that had scored the point.

Importance of Game

The Pawnee legend, The Girl Who Was the Ring, describes how seriously the game was taken by the players and how arguments could escalate in determining who had scored. In this story, a girl who is able to summon the buffalo so her brothers can easily kill them for food is taken by the buffalo and transformed into a chunkey ring. The buffalo then use the ring regularly to play the game until the girl who was the ring is rescued by Coyote. At points, the buffalo players argue so heatedly over who has scored that they almost come to blows.

In his introduction to the legend in The Punishment of the Stingy and Other Indian Stories (1901), Grinnell provides a description of the game as he saw it played in the late 19th century by the Pawnee:

Of all the games played by men among the Pawnee Indians, none was so popular as the stick game. This was an athletic contest between pairs of young men and tested their fleetness, their eyesight, and their skill in throwing the stick. The implements used were a ring of six inches in diameter, made of buffalo rawhide, and two elaborate and highly ornamented slender sticks, one for each player. One of the two contestants rolled the ring over a smooth prepared course and, when it had been set in motion, the players ran after it side by side, each one trying to throw his stick through the ring. This was not often done, but the players constantly hit the ring with their sticks and knocked it down, so that it ceased to roll. The system of counting was by points, and was somewhat complicated, but in general terms it may be said that the player whose stick lay nearest the ring gained one or more points. (49-50)

As noted, spectators would often gamble on the outcome of the game, and so it became a source of revenue for some and a dramatic loss in status and fortune for others. Losers are said to have taken their own lives rather than live with the shame of having to surrender their personal wealth or even their freedom after wagering too heavily on a game.

Although the game seems to have caused some serious arguments, it was also played to settle disputes between parties. Conflicts that might have resulted in a serious injury or death could be resolved through a game of chunkey, which brought the entire community together to play or watch. As noted by Zimmerman, the game also sometimes served religious purposes or marked an important event in the life of the community. The game also served to sharpen the skills of the young hunters and warriors who were responsible for providing the community with food, resources, and defense.

Conclusion

The popularity of the game declined in the early 20th century, possibly because of increased interest in stickball or, more likely, due to the focus of the US government-approved American Indian Boarding School curriculum on assimilation by re-educating Native American youth to reject all aspects of their culture and heritage. Chunkey only began to experience a revival in the 1960s and 1970s and has only reached a wider audience in the past 30 years.

Today the game is played by members of many different Native nations, such as the Cherokee, Pawnee, Chickasaw, Mandan, Lakota Sioux, and others. Mr. Cole Hogner, the Cherokee Nation Native Games Chunkey Coordinator, describes how the game is experienced presently:

It still holds a lot of value as what it was intended for originally. The origin of it was intended to bring everybody in the region [such as] Cahokians, farmers, immigrants, visitors, all together…Just like stickball, just like anything else, there’s a lot of camaraderie and it’s kind of a brotherhood, so to speak. (Bark, 3)

The Cherokee nation and others include chunkey now in social gatherings and celebratory events such as powwows and other kinds of festivals. The chunkey stone is understood as belonging to all the people of the community, as it was in the past, and, in this same way, the people all own the game itself, no matter what nation they belong to or how it is played, just as it was long ago.