The Battle of Buxar (aka Bhaksar or Baksar) in Bihar, northeast India, on 22-23 October 1764 saw a British East India Company (EIC) army led by Hector Munro (1726-1805) gain victory against the combined forces of the Nawab of Awadh (aka Oudh), the Nawab of Bengal, and the Mughal emperor Shah Alam II (r. 1760-1806).

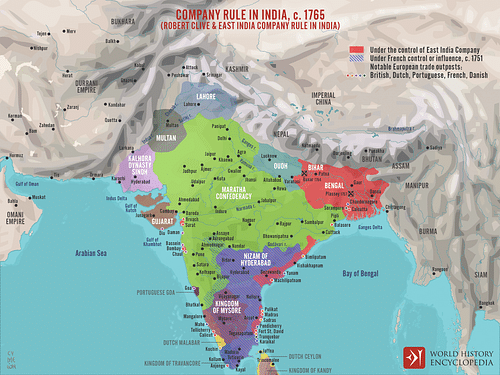

Victory against the odds at Buxar led to the EIC gaining the crucial rights to raise taxes in various regions, a huge boost to the company's coffers, which allowed it to pursue further territorial conquests across the subcontinent.

East India Company Expansion

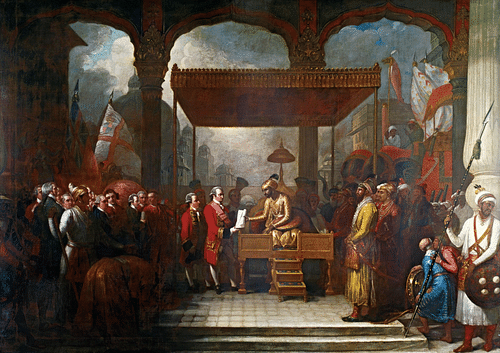

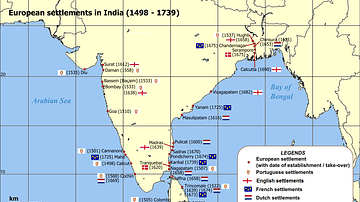

The East India Company was founded in 1600, and by the mid-18th century, it was benefiting from its trade monopoly in India to make its shareholders immensely rich. The Company was effectively the colonial arm of the British government in India, but it protected its interests using its own private army and hired troops from the regular British army. By the 1750s, the Company was keen to expand its trade network and begin a more active territorial control in the subcontinent.

Robert Clive (1725-1774) won a famous victory for the EIC against the ruler of Bengal, Nawab Siraj ud-Daulah (b. 1733) at the Battle of Plassey in June 1757. The Nawab was replaced by a puppet ruler, the state's massive treasury was confiscated, and the systematic exploitation of Bengal's resources and people began. 'Clive of India' was made the Governor of Bengal in February 1758 and, for a second spell, in 1764. It was time for a new British name to grab the colonial limelight, though, one Major Hector Munro.

The Indian Allies

The EIC faced a combined alliance of three powerful states. First, there was Awadh, a state in the middle Ganges region of northern India, ruled autonomously by nawabs under the nominal suzerainty of the Mughal Empire (1526-1857). The capital of Awadh was Lucknow, known for its fine architecture, the state was wealthy, and the current nawab was Shuja-ud-Daula (r. 1754-1775). The second ally was the ex-Nawab of Bengal, Mir Qasim (aka Kasim, r. 1760-1764). Qasim was keen to resist pressure from the EIC to grant trade privileges to both the company and private individuals. When the EIC replaced Qasim as the nawab with his own father-in-law, Qasim was obliged to react decisively. Qasim had been ruler of this immensely rich region in the northeast of India since 1760, and he was eager to get it back again. The third member of the alliance was the Mughal emperor, Shah Alam II. Based in Delhi, the emperor did not usually intervene directly in disputes between the EIC and vassal states, but he was now intent on better controlling Bengal and not leaving it in the rapacious hands of the EIC.

Emperor Shah Alam, after failing to capture Patna from the EIC, assembled a well-trained army and marched to the eastern side of the continent. His infantry commander was the wily Frenchman Jean Baptiste Gentil. Armies led by Shuja-ud-Daula and Mir Qasim joined the emperor en route. The total force may have numbered around 50,000 men. The army marched through early monsoon weather, and Shah Alam ordered camp near the fort of Buxar on the Awadh-Bengal border. The position was a good one, protected on his left side by the Ganges river, on his right by the Torah nala stream, and in front by earthworks, the emperor decided to sit out the monsoons until proceeding into Bengal.

Munro's Army

As news of this massive army reached EIC headquarters, a response was immediately organised. Major Hector Munro was selected to lead an EIC army to face the triple alliance. Not untypically for the EIC's approach to warfare, Munro had nowhere near the same numbers to command as the opposition: a mere 4,200 men (3,000 of which were sepoys or Indian troops) according to some historians, or around 900 Europeans and 7,000 sepoys according to others. Munro also had a 1,000-strong cavalry group. Numerically inferior, the British really had two advantages. First, Shah Alam had been wasting his time on easy living and entertainment in his camp at Buxar, allowing his men to grow idle and unfit, and they, in turn, allowed their equipment to fall into disrepair. The second advantage was Munro. The historian W. Dalrymple describes the EIC major as: "one of the most effective British officers in India, a dashing cool-headed but utterly ruthless 38-year-old Scottish Highlander" (197-8). Above all, the major's emphasis on discipline, that is following orders and keeping formation even in the chaos of battle, proved to be the difference between the two sides. Munro left Bankipur on 9 October and headed for Buxar, which he arrived at on 22 October.

Battle

Gentil urged the emperor to immediately take the initiative when the British army arrived near Buxar. The Frenchman pleaded:

Now that the English have not yet lined up in battle-order, now that the barges have not yet drawn up along the river to unload their weapons and military equipment, now that they are all busy putting up their tents – now is the moment to attack!

(Dalrymple, 198)

The emperor did not take the advice and merely ensured his treasury and women were sent to the safety of Faizabad. It may have been the emperor originally planned to remain where he was and fight a defensive battle, but on realising the small size of the British army he faced, he ordered an attack just after dawn. By that time, though, Munro had already arranged his troops, and he now began the customary artillery barrage. The emperor, in any case, ordered his cavalry to charge the enemy, leaving the protective walls of their camp to cross the battlefield. The emperor also ordered his own artillery to fire on the enemy. The Indian cannons were larger and so could fire heavier shot, but the 20 British pieces had the crucial advantage of being more mobile, permitting Munro to place them where most needed as the battle developed. The better-trained EIC gunners were also capable of firing off more rounds in any given time period than the opposition.

The progress of the Indian cavalry was now impeded by the marshland that divided the two armies. The emperor's Naga and Afghan cavalry went around the marsh and attacked the British positions from behind. The EIC reserves, which would normally have only been used at the end of the battle, now faced the cavalry out of necessity. The Indian riders then made the mistake of not pressing home their advantage and concentrating instead on capturing the British camp and stores, including the treasury and ammunition boxes. In the subsequent round of looting, the Indian and Afghan cavalry took no further part in the battle.

With their rear lines exposed and obliged to defend themselves against the marauding cavalry, with a number of their compatriots already captured, and with everyone remaining still under fire from the Indian artillery, it was at this moment that Munro's famous emphasis on discipline came to the fore. The EIC troops, including the sepoy units, crucially maintained their defensive square formations even when the situation looked so hopeless that the emperor was convinced he had already won the battle. Munro ordered the barges to gather to take the men in a retreat across the river, but in the time it took to carry out this order, it became clear to the major that the Indian cavalry, fully occupied with looting, had presented him with a golden opportunity for a counter-attack. Munro gathered his men and attacked in force the left flank of the Indian army, using disciplined and coordinated musket fire.

The British marched forward in a column and smashed their opponents into disarray. There was a chaotic retreat of men, camels, bullocks, and elephants. The emperor fled across the Torah nala, using a temporary bridge of boats, while his loyal Naga troops fought a brave but fatal rearguard action. The retreating Indians who managed to get to the river and wade across it were picked off by EIC riflemen so that the waters became choked with bodies. Munro had snatched victory from the jaws of defeat.

Casualties had been heavy on both sides. The EIC suffered around 850 dead, wounded or missing, an unusually high proportion (although some historians put the figure even higher, around one-quarter of the total British force at Buxar). The emperor's armies suffered perhaps as many as 5,000 dead (although more conservative historians put the figure around 2,000). As was the tradition, the emperor's camp was looted. An added bonus for Munro was the 130 or so cannons he captured. After the battle, Mir Qasim fled to the west, Shuja-ud-Daula recognised the supremacy of the EIC, and the Mughal emperor, ever keen to support victors, not losers, switched his support to the British.

Aftermath

After the victory, Shah Alam II signed the Treaty of Allahabad on 12 August 1765. The emperor, after a suitable period to make it look like he was giving a gift rather than a concession forced upon a loser, awarded the EIC the perpetual right to collect land revenue (dewani) in Bengal, Bihar, and Orissa. This was a very important development since it ensured the Company now had vast resources to expand and protect its traders, bases, armies, and ships. In return for Shah Alam's concession, the EIC guaranteed that the state of Bengal would pay him an annual fee of 2.6 million rupees. However, the Treaty of Allahabad had also stipulated that the EIC be paid the fantastic sum of 5 million rupees to cover the expenses of the recently concluded war. Now fully in control of Bengal with its new puppet nawab (Nazim-ud-Daulah), the EIC eventually obliged Awadh to sign a subsidiary alliance with it in 1801. In 1856, the EIC formally annexed the state. Into the 19th century, the East India Company was by far the most powerful force on the subcontinent, but the foundations of its vast empire had been laid at Plassey and, above all, Buxar.