The Napoleonic Concordat of 1801 defined France's relationship with the Catholic Church for over 100 years. The Organic Articles were added in 1802 and provided state recognition of the Reformed and Lutheran confessions alongside the Catholic Church. During the 19th century, political upheaval and attempts to reestablish Catholicism as the state religion led to the termination of the Concordat in 1905.

Religious Pluralism in France

Since the beginning of the 16th century, French Protestants struggled for legitimacy, religious equality, and civil rights. They faced opposition from the monarchy and the state religion, the Roman Catholic Church. To end the French Wars of Religion (1562-1598), Henry IV of France and the Edict of Nantes provided protection for Protestantism in 1598. The edict was revoked by his grandson Louis XIV of France (r. 1643-1715) in 1685, which led to the War of the Camisards (1702-1705). With the Edict of Toleration in 1787 under Louis XVI (r. 1774-1792), French Protestants were granted civil rights and permitted to live in the kingdom without religious discrimination. Catholicism remained the state religion and non-Catholics remained excluded from positions in public service.

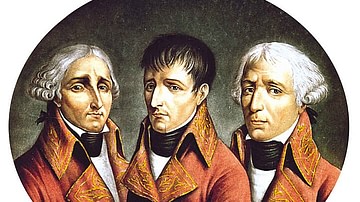

At the dawn of the French Revolution in 1789, the Declaration of the Rights of Man and of the Citizen announced a new era of religious tolerance and permitted access to civilian and military positions for non-Catholics: "No one may be disturbed on account of his opinions, even religious ones, as long as the manifestation of such opinions does not interfere with the established Law and Order" (Article 10). For a time, this statement remained an ideal yet served as a reference point and foundation for changes to come. After the French Revolution (1789-1799), French Protestants found a greater measure of protection with the Concordat of 1801 and the Organic Articles in 1802 under Napoleon Bonaparte (l. 1769-1821).

Napoleon & the Concordat

The tumultuous years of the French Revolution were marked by anti-religious sentiment, the seizure of church property, the Reign of Terror (1793-1794), and the process of dechristianization. In 1789, the Catholic Church was forced to relinquish its possessions and land holdings. In 1790, the Civil Constitution of the Clergy provoked a schism. The Church was nationalized and its ministers were elected by church members without the approval of the Church. In 1794, all exterior manifestations of worship were forbidden, and the Church was confined to the private sphere. When Napoleon came to power in the coup d'état of 18 Brumaire (9 November 1799), he began to reverse many of the gains of the Revolution, initially as First Consul (1799-1804) and then as emperor (1804-1814/15). An alliance with the Catholic Church became a political necessity since many French were still attached to their traditional religion. The state needed the church to assume tasks, such as education, that the state did not wish or was unable to administer.

Napoleon's arrival to power coincided with the election of Pope Pius VII (served 1800-1823). Napoleon desired to establish religious peace and Pius desired to restore the unity of the Church. The result was the 17 articles of the Concordat to define the status of the Catholic Church in France, signed in July 1801 and ratified in September of that same year.

According to the preamble, Catholicism was no longer the state religion as it was prior to the Revolution yet remained "the religion of the great majority of the French citizens." Article 1 stipulated that "the Catholic, Apostolic, and Roman religion will be freely exercised in France." The first consul (Napoleon) appointed Catholic bishops (Article 5) who swore "to observe obedience and loyalty to the Government established by the Constitution of the French Republic" (Article 6). Pope Pius VII promised that "neither he nor his successors will disturb in any manner those who have acquired alienated ecclesiastical possessions" (Article 13). In turn, the "Government will assure a fitting maintenance for the bishops and the curates whose dioceses and parishes will be included in the new circumscription" (Article 14).

Protestants & the Organic Articles

The Organic Articles were Napoleon's unilateral appendix to the Concordat promulgated on 8 April 1802. They were added to prevent a return to past religious conflict and for the reorganization of the Protestant religion. One section of the Organic Articles provided 77 additional articles for the Catholic Church. Another section addressed the Protestant religion with 44 articles of regulations, limitations, and restrictions. There were specific regulations for Reformed and Lutheran churches and general regulations for both Protestant confessions, together brought under the protection and surveillance of the state. For example, Article 3 required pastors to pray for "the prosperity of the French Republic and for the Consuls", and all seminary professors would be "appointed by the First Consul" (Article 11). Protestants were divided in their views of the Concordat and Organic Articles, which brought churches into the service of the state.

After over 100 years of struggle after Louis XIV and the Revocation of the Edict of Nantes in 1685, it was not surprising that many Protestants welcomed the Concordat and Organic Articles imposed by Napoleon. They offered a measure of religious pluralism and brought religious peace, although there were occasional local exceptions of violence. Protestantism had lost half its population through wars and emigration, and it appeared that its spiritual forces were spent. Protestants were given access to most public positions, and pastors became paid employees of the state with an oath of loyalty to the state. Protestant churches were reorganized into consistories tasked with calling pastors to churches with government confirmation. In time, some Reformed church leaders came to believe that it was no longer possible to defend the arrangement. They called Reformed believers back to their Reformation roots and the doctrines known as Calvinism. From 1820 to 1848, independent non-concordataire churches of professing believers were founded and existed alongside concordataire Lutheran and Reformed churches.

Bourbon Restoration

The Bourbon dynasty's restoration followed Napoleon's fall and exile in 1814. Louis XVIII of France returned from exile and reigned from 1814 to 1824 except for a brief period when Napoleon escaped from the island of Elba and returned to the throne for one hundred days. Louis XVIII's return was accompanied by a spirit of religious retaliation. He made it known that he did not want to be king of a divided France. The Charter of 1814 established a constitutional monarchy, guaranteed civil liberties and religious toleration, and reestablished Catholicism as the state religion. The Concordat remained in force with protections for Protestants and Jews, but the monarchy and the Catholic Church were once again united. In 1821, bishops of the Catholic Church were given authority in religious education in secondary schools, and primary school teachers required a teaching certificate from a bishop.

During the reign of Louis XVIII's successor, his brother Charles X of France (r. 1824-1830), the power of the Catholic Church increased. The July Revolution in 1830 forced his abdication and the election of King Louis-Philippe (r. 1830-1848). Under his reign, the kingdom again experienced counter-revolutionary pressures. The Catholic Church, however, was seen as necessary for national stability.

Second Empire

The February Revolution of 1848 overthrew the Bourbon monarchy setting the stage for the short-lived Second Republic (1848-1851) and the election of France's first president, Louis-Napoleon Bonaparte (l. 1808-1873), a nephew of Napoleon Bonaparte. In 1852, he declared himself Emperor Napoleon III with the support of both the papacy and the majority of French Catholics. During the Second Empire (1852-1870), relations with the Catholic Church became more cordial, with a corresponding loss of religious liberty and the repression of non-concordataire churches.

Education was the issue that crystallized the combat between the clerical and anticlerical parties in the 19th century. In 1850, under the Second Republic, the Law Falloux gave the Catholic Church greater influence in primary schools. The law granted the Church complete liberty to open religious schools and submitted public establishments to religious control. There was a revival of anticlericalism and hostility toward ecclesiastical institutions, and Republicans intensified their efforts for the separation of church and state.

The year 1870 was pivotal in the political and religious life of France. On 18 July, bishops of the Catholic Church from around the world gathered at Saint Peter's Basilica in Rome to vote their approval of the dogma of the infallibility of the pope. In speaking ex cathedra, the pope was preserved from error in faith and practice. With this proclamation, the Church effectively put an end to papal opposition from the Gallican wing of the French Church.

On 19 July, one day after the papal proclamation, France declared war on Prussia. Emperor Napoleon III had already stood against the Prussian war machine and had decisively defeated the armies of Denmark and Austria in 1864 and 1866, respectively. This time France suffered a humiliating defeat in a mere six weeks. One of the ironies of this defeat was that descendants of persecuted and exiled French Huguenots from the previous century were counted among Prussia's military forces. Another irony of history was that the defeat in September 1870 took place at Sedan, a city that was a center of French Protestantism until the persecution following the Revocation. Following the resounding rout of the French army, the emperor abdicated his throne after an uprising in Paris and brought an end to the Second Empire. Louis-Napoleon III was imprisoned by the Prussians and went into exile in England, where he died in 1873. The defeat of the French in 1870 and the constitutional uncertainty provoked by the fall of the Second Empire resulted in a crisis of leadership and conscience.

Third Republic

The end of the Second Empire was followed by the Third Republic (1870-1940). The educational laws enacted between 1881 and 1882 under Jules Ferry (l. 1832-1893) attempted to reverse the gains and resurgence of the Catholic Church made under the Bourbons and Napoleon III. The Catholic Church lost influence when it was removed from public schools. Public education became free, compulsory, and secular. Religious instruction was eliminated from the curricula. In 1882, a law was adopted to secularize primary education. To assure confessional neutrality in elementary schools, the law removed all references to God and inserted moral and civic instruction separated from religious references.

Republicans continued their opposition to the Catholic Church and the return of the monarchy. They firmly believed that the Revolution had snatched the French people from the slavery in which they were held by religion and the monarchy and claimed that Catholicism prevented the faithful from attaining earthly happiness. Both Republicans and religionists tended to focus on the worst aspects of their adversaries. Their mutual hatred prevented them from working together in areas for the common good.

The Third Republic also witnessed, for the first time in French history, a Protestant influence that had been minimal until this time. Since religious instruction in the schools was Catholic, Protestants favorably viewed laws of secularism regarding education. They advocated educational reform, the separation of church and state, and social action.

Conclusion

The Concordat and Organic Articles had been a noble attempt at religious pluralism to restore domestic tranquility and prevent a return to open hostility between Catholics and Protestants. For one hundred years it regulated the relations between religions and the state in France. Political events and the increased influence of the Catholic Church during the concordataire period favored the rise of anticlerical Republicanism and the movement toward a secular form of government free from religious entanglements and royalist aspirations. The Concordat was abrogated by France’s 1905 Law of Separation of Church and State. Owing to historical factors the Concordat survives today in Alsace-Moselle in eastern France. This region was annexed by Germany in 1871 after France's defeat in the Franco-Prussian War and was returned to France following the defeat of Germany in World War I (1914-18). A condition of reintegration into France was the continuance of the Concordat.