In the 17th century, many groups of British Christians rose and fought against religious intolerance and corruption. The Puritans sought a return to biblical religion and a purified form of Christianity in England. This resulted in the Puritan Revolution, as well as a migration to America to find a place to worship God in what they considered the 'correct' fashion.

Another group, called the Quakers, who approached Christianity from an extreme spiritual interpretation, also pushed against the status quo. They were often criticized and abused for their faith, both by the religious and the civic world. One of their members, William Penn (1644-1718), was influential in the establishment of that faith in America and was responsible for creating a colony in America where a government was established that earnestly and actively sought to protect religious and civil rights. Quaker specialist Bonnelyn Young Kunze writes in her article:

William Penn's chief claim to historical fame was his founding of the Quaker colony of Pennsylvania, as well as his prolific writings in defense of Quakerism and religious toleration in England. (170)

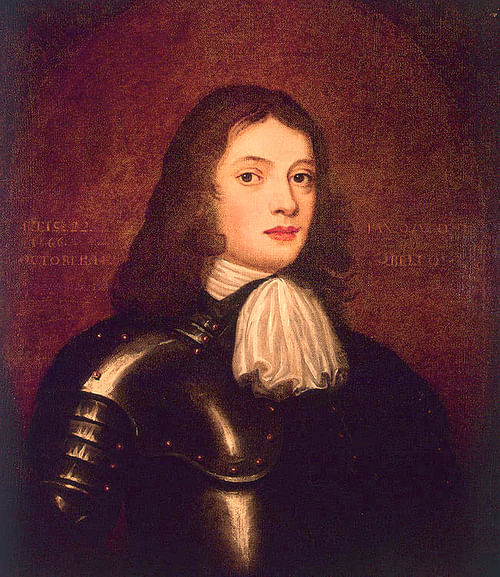

Early Life

William Penn's parents were an interesting mix. According to American sociologist and historian Harry Wildes, Penn's father was an admiral in the royal navy and was "by conviction pro-Anglican and royalist" (Wildes, 10). He was a stern and serious man who lived and worked amidst the political chaos of the time. Not a great deal is known about Penn's mother except that she was "energetic, extroverted" (Wildes, 9), and was left alone for long periods of time to raise her children by herself. Her initial style of parenting was unorthodox, but later on, she attempted to improve upon her approach.

William Penn was described as quiet and introspective, although he was reported to have "exhibited a strong mystical streak. By his own account, he had mystical experiences by the time he was twelve or thirteen" (Dunn and Dunn, 4). No doubt this would be a determinant factor in his joining the Quakers.

At this same time, Penn and his father had "fairly stormy relations" (Dunn and Dunn, 4) that are documented in correspondences between the two. He often rebelled against his father's wishes and demands of him. This rebellious streak led him into trouble a great deal as a young man. He was expelled from Oxford in 1662 for objecting "to the prayer book and to ritual which seemed too popish" (Dunn and Dunn, 7) and was severely punished for his involvement with the Puritans. According to historian Hans Fantel, Penn's father, hoping to separate him from the "company of subversives" (Fantel, 45), sent him abroad to Paris, France. There, he mingled with many great men, including King Louis XIV of France (r. 1643-1715) and Moïse Amyraut (1596-1664), a famous Protestant Christian humanist.

During this time, contrary to what his father hoped to accomplish, Penn honed his challenging views even more, but he did learn some tact and diplomacy. He returned home a more mature, even-tempered man (much to his parents' delight), but he still had questions. His father, too, questioned why Penn was wasting his time on so much theology and enrolled him in law school. Fortunately for Penn, he was able to spend more time with his father and observed him in his military duties, which no doubt influenced Penn's later administration of the Pennsylvania colony.

At this time, Penn was also introduced to the English royal court, providing contacts that would serve him well later on. As a responsible adult, Penn was given more family responsibilities, and his father sent him to Ireland to take care of some family holdings and estates.

Penn Befriends The Quakers

While away from his family's influence, Penn began attending Quaker meetings. These meetings were forbidden under the Claredon Code, which "forbade all religious gatherings except those under the auspices of the official Church of England" (Fantel, 66). Again, Penn found himself pitted against authority concerning his religious rights. During one meeting, Penn had the opportunity to listen to Thomas Loe, a famous Quaker leader. There, Penn was deeply affected by what he heard.

]Penn] recognized the Quaker meeting as a community through which a free faith of separate individuals could take on socially effective forms. ... Penn had found ... a practical intersection of faith and society." (Fantel, 68)

Eventually, Penn joined the Quakers and was subsequently arrested and jailed after a meeting of theirs was discovered with him in attendance. He was given the opportunity to escape imprisonment by a politically savvy judge, but he stood fast to his ideals. At age 22, William Penn had declared himself a Quaker, much to his father's sorrow and anger.

Penn's conversion was predictable considering his mystical background. With the Quakers, "He could share ... powerful feelings of possession by the spirit and enjoy a certain freedom to interpret and act on those feelings in an individual way" (Dunn and Dunn, 5). Furthermore, this new faith of Penn's also managed to justify some of his belligerence with his parents. Being a Quaker "gave Penn good religious grounds for disobeying his parents" (Dunn and Dunn, 6) if they made religious demands that challenged his beliefs. The ultimate result of this was bad relations with his father until his father's death in 1670.

Penn not only had difficult relations with his family but also managed to get himself in much trouble with the Church of England. He was imprisoned in the Tower of London in 1667 for writing a tract entitled, The Sandy Foundation Shaken Speaking Against the Doctrine of the Trinity. While in the Tower, he wrote No Cross, No Crown and Innocency with Her Open Face, and he later went on to write several other works. Many of his tracts were written by Penn to defend his Quaker brethren or in defense of religious freedom. According to Quaker historian Melvin Endy Jr.,

Penn's originality as a tolerationist consisted largely in the ingenuity with which he drew up variations of arguments intended to convince his readers that it was to their interest as individuals, citizens, and merchants to replace coerced uniformity with the blessings of toleration. (Endy, 323)

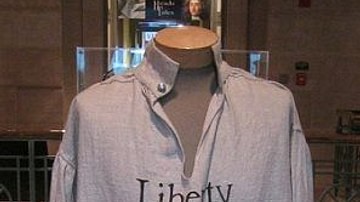

Penn also began to preach, and in 1671, he was arrested and imprisoned for preaching at a worship service. Still, "Despite filthy and crowded conditions, Penn wrote three lengthy tracts and several epistles focusing on liberty of conscience" (Adams and Emmerich, 63). He took the matter of religious liberty very seriously and hoped to use his talents in a just and righteous cause. He found that cause in the establishment of a Quaker colony in America. There, Penn hoped to put his religious and political beliefs to the test in one grand 'Holy Experiment.'

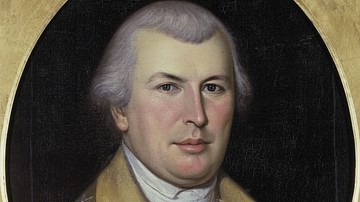

The Pennsylvania Colony & the Holy Experiment

In 1680, an older debt of King Charles II of England (r. 1660-1685) was passed from the deceased Admiral Penn to his son, William Penn, but instead of that money owed to him, young Penn asked to receive "proprietary title to a huge territory in America" (Dunn and Dunn, 41). He asked for this because “by obtaining the proprietorship to a Quaker colony, he could vastly expand his service to his coreligionists and to the general cause of religious and political liberty – and at the same time greatly enlarge his property holdings" (Dunn and Dunn, 42). It was Penn's overwhelming desire to "create a theocentric society without resorting to compulsion in religious matters" (Adams and Emmerich, 66). In that utopian society, Penn "sought to reconcile liberty and authority in his frame of government" (Stern, 85).

Therefore, Penn established this colony with the hope that religious toleration would be maintained without abuse by the government. He "argued that intolerance was contrary to reason. To sacrifice the liberty and property of a man for religious causes would not win the loyalty of that man for the prince. Enforced conversion ... resembled forced marriage" (Beatty, 134). Of course, as the head proprietor and governor of those holdings in America, Penn had complete authority as detailed in the Pennsylvania charter of 1681. However, he used this position as much as possible to procure liberties for the colonists and not to help himself. Sadly, he did not succeed as fully as he had hoped.

Penn's earliest plan of government was called the Fundamental Constitutions of Pennsylvania. This document, probably drafted by Penn himself, was the "most liberal of the early plans of government for Pennsylvania. Its opening section declares religious liberty for all inhabitants" (Soderlund, 96). Furthermore, it was extremely democratic in spirit and law. Much of the power rested in the hands of the people, rather than with the governor and the administrative council.

Unfortunately, this plan was rejected for political reasons at the time and was neither ratified nor signed by the new colonists (not even by Penn). Instead, a new Frame of Government was enacted. It had a stronger hierarchical style of government with most of the earlier plan's extreme democratic representation being removed from its provisions. According to Historian Jean Soderlund, it still guaranteed "religious freedom to all inhabitants who believe in one God" (119) and established an electoral legislative system, prohibited taxation without representation, and guaranteed free trade.

This experiment in religion and government thrived, with new colonists coming in from all parts of Europe. Interestingly, not all immigrants to Pennsylvania were Quakers. There were many Puritans, Catholics, and people from other sects, but Penn's system of government still incorporated them. Things began to change for Penn and his colony, however, with the advent of the Glorious Revolution (1688-1689).

Penn's association and friendship with the fleeing king of England made him a hunted man, and he had to spend some time hiding to save his life. During this period, the control of the Pennsylvania colony was taken away from him because of the lack of military support for the French-Indian War by its colonists. Eventually, Penn regained control in the colony, but by that time, there was great "political disorder, religious factionalism, and a General Assembly hostile to his executive power" (Adams and Emmerich, 68).

Ever the man of peace, Penn approved a Charter of Privileges in 1701, which gave the Pennsylvania legislature even greater powers. He also returned to England to fight against a bill in Parliament seeking to re-establish royal control over the colonies, never to return to his colony in Pennsylvania again. In 1718, he died in England from complications from several debilitating strokes he suffered earlier that year. Initially, Penn's charter was split between his sons, but eventually, the Penn family sold it back to the Crown.

Legacy

Penn's Holy Experiment proved true to its name. It was a testing ground for new and innovative ways of dealing with religious tolerance alongside civic administration. It showed that, at least for a time, the two kingdoms of faith and government could co-exist in ways that were free and fruitful. This form of society could prosper and flourish despite hardships, military struggles, and religious diversity.

The colony in Pennsylvania did more than just succeed for itself; it provided the framework and example for other colonies to follow in America. Even beyond that, it greatly influenced the eventual constitution of the United States of America. Adams and Emmerich have stated, "No other colony inspired the Founders more in the area of religious liberty than Pennsylvania" (68).

This incitement did not just happen on its own; William Penn was the force responsible for the creation of this important colony. As Edward Beatty concluded, Penn's "great enterprise in the New World was an endeavor to set up a social order blessed with religious toleration and controlled by humanitarian ideals" (305). Without him, there may not have been as strong a desire to create an environment for the cultivation of religious freedoms.