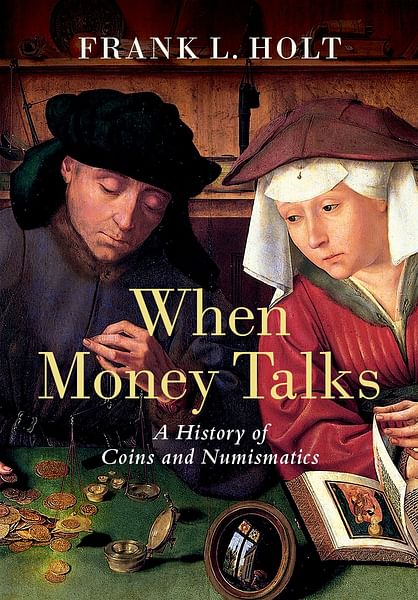

Join World History Encyclopedia as they talk to Frank Holt about his new book When Money Talks: A History of Coins and Numismatics published by Oxford University Press.

Kelly (WHE): Thank you so much for joining me today. Do you want to start off by telling us a bit about what your book is all about?

Frank (Author): Thank you for having me. The book is subtitled A History of Coins and Numismatics, and though coins may seem mundane and the sort of thing that you carry around in great numbers and yet hardly ever look at, they are actually like an encyclopedia of world history. I have become very interested over the years in how much historical information can be derived from examining coins. The study of coins and the curation of coins is called numismatics, and so the book covers both the history of money in general, coins in particular, and the history of the study of coins from ancient times. Coins were studied almost as soon as they were invented down to our own day.

Coins came along around 630/620 BCE, c. 2600 years ago. In the book, I talk about how the world managed before coins were invented. Then once coins were invented by the Lydians, they were quickly copied and expanded by their neighbouring Greeks. From that point on, coins became an enormously significant factor in world history, not just for economic reasons, but they speak of our social, intellectual, artistic, religious, and military lives.

As a result of that, I found that as an ancient historian, often bereft of information, coins provide our best answer. As I say at the beginning of the book, I did not go into history for the money. I went into money for the history. That is because as a grad student, I became interested in what happened to those Greeks that Alexander left behind in what is now Afghanistan. That is a marvellous story, but it is a story that can only really be told through the coins that were left behind through numismatics. As a grad student, my professor said, well, you want to study that? You better learn something about coins, young man. I did and have been doing so ever since.

Kelly: Wow, it is pretty spectacular that something so small and what we would think of as mundane can tell you so much about these ancient people. That information you would not be able to get from anything else.

Frank: In a sense, it is the small and mundane that makes it so important to us. I think of them as tiny disks of information technology in which you intentionally cram as much data, text and image and ideas, onto as small a surface as you can. Because it is mundane, because it is used in everyday life, it gets handed and transported from here to there and everywhere. So, coins quickly became the first means of mass communication in world history. That is because they were small and transportable, and it is because they were mundane in the sense that they were woven into the fabric of everyday life. Though we greatly admire magnificent inscriptions, obelisks, and these grandiose statements, it is really the coins that speak to us most about what was going on in vast stretches of not only the ancient world but in the medieval and modern world as well.

Kelly: Do you look at it from a global sense in your book, or do you focus more on a particular region?

Frank: Because my background is ancient history, and more specifically ancient Greek and Roman history, I would say that the weight sort of falls in that direction. When I try to find an example of how coins were used to do this or that, the first things that come into my mind are from my own fields of study. However, one joy of writing this book was that it challenged me to move beyond the familiar frontiers of my own research and to think about how coins were used in the Islamic world, in East Asia, in the medieval period and right down to the modern day. I even tackle things like cryptocurrency and the future of coinage in the book. It does span the whole breadth of world history for the last 2600 years, but in its examples, it is weighted, I think, toward ancient Greece and ancient Rome.

Kelly: It is a massive undertaking. I am assuming that there has been a lot of different uses for coins throughout that time period.

Frank: Absolutely. The variety is staggering. There are tens of thousands of different kinds of ancient Greek coins, tens of thousands of different varieties of ancient Roman coins, and we have not even mentioned all the coinages that have come along since then in world history. I challenge my students to take a look at modern US coins, the ones they are most familiar with, and they turn out not to be very familiar with them at all. If I ask them who is the president on the dime, they have no idea who that person is, but then they can find an incredible amount of history on them. I tell them the cheapest education you can get in world history is to take a handful of coins out of your pocket and you can survey an incredible number of historic events.

Kelly: You are right, people put so much information on coins. Even now, I am just thinking of all the different types. I know when there was the Olympics, our two-dollar coins would have a different colour band and then you could try to collect all five colours. And that is just a couple of months where these coins are being produced.

Frank: That is true. Coins tend to become what I might call fossilized fairly quickly, but if you look at American coins, future generations, 2000 years from now, are going to be confused about how long Abraham Lincoln was President of the United States. He has been on coins for a very long time, and George Washington and Thomas Jefferson even longer. Our coins tend to change rather slowly, though when they do, it is quite significant. We now have a new series of quarters coming out in the United States that feature prominent women in American history. Though certain attempts have been made in the past, this is broad-reaching in that respect.

However, in the ancient world, where coins were seen as mass communication, the coins changed on a very regular basis. It was like picking up a newspaper. Who is the emperor today? Sometimes in ancient Rome, it was different from one day to the next. Coins were the answer to questions like, "Who is the Roman emperor today?" "Have we won any big battles lately?" "Has anybody built any magnificent structures?" or "Which gods and goddesses are trending right now in our civilization?" Coins were a constant reminder of what was going on in the world around you and at a much quicker pace than we are familiar with today. But as I say, even today, there are significant changes that occur, and when they do, we all take notice of them.

Kelly: That is fascinating because when you do research on the Roman emperors, it is always a coin that comes up. But even during their reign, coins can change, and sometimes you have two people co-reigning.

Frank: Absolutely, and let us not forget about their wives! The empresses come on coins, some of the most wonderful coins where an emperor commemorates a recently deceased wife by showing her empty throne and her sceptre lying across an empty throne and a peacock, the symbol of resurrection in the afterlife. We do not often think of emperors as being that touching, that emotional, but that kind of thing really does come through. Their children will appear on the coin, too. So, it is not just the emperors themselves. When we look at the coins, we get a fairly balanced and deep, rich history of not only their public achievements but also of their private lives.

Kelly: Having that glimpse into the private lives of these people that lived so long ago is just amazing. Why did you decide to write this book? Why did you decide to go through this history of coins?

Frank: I have been teaching numismatics at the university for about 40 years now. Though I do not teach it every year, I teach it fairly often, and it is always an extremely popular course. Students often tell me, "I do not know what numismatics is, I just signed up for the course because people told me you are a good professor and it has something to do with the ancient world, so I thought I would take it." Once they start handling coins and realizing how much there is to be learned from them, that fire is lit in them. It has always been something that energizes me whenever I teach the course. I have taught over several years, and I have developed a lot of interesting, I think, and new ideas about coins. Some of them are in the book. Treating coins as though they were sentient beings, for example, is not a way that most people think of coins, as having control over us more than we have control over them.

I had written and published eight books up to that point, and then I decided I want to write something for everyone about coins, for someone who has never looked at a coin. I wanted to reach the general public. So, I applied for a National Endowment for the Humanities grant; they have a public scholar's program for scholars to take a subject that is rarely taught or talked about in the academic world, like numismatics and produce a book that will reach a general public. I applied for the grant and was very fortunate; I got it. It gave me some time to expand what I knew about coins. I knew a great deal about a few coins, and I knew a little bit about a great number of coins, but I did not know a lot about a lot of coins. The grant provided me with the opportunity to do the research.

In some ways, it is my way of giving back to numismatics some of the joy that it has brought to me unexpectedly. I never collected coins as a kid. I never intended to do anything with numismatics when I went to study classical history. It just moved in that direction, and I wanted to share that joy with as many readers as I could.

Kelly: It is nice knowing that you have written it with the intention that anyone can pick it up and learn about coins and numismatics. In your research, you had to learn a lot about a lot of coins, and add to your prior knowledge. Was there something that was particularly surprising or exciting or interesting that you learnt while writing the book?

Frank: A lot of things. I was an English major as well as a history major and had a great fondness for English Romantic poetry. One of the things I wanted to do when I was writing this book was to show not just where coins are situated in our economic lives, but where they are in literature. Where do coins show up in the ancient Greek comedy or Roman literature, for example, in Aristophanes' or Plautus' work? Where do coins show up in modern sitcoms on television? Where do they show up in current literature? One of the things that I found quite exciting was how many places I was able to find and draw information from coins. I would have thought before I did this research that nothing could be less congruous than poetry on the one hand and a coin on the other, and as it turns out, they interplay with each other quite well.

Kelly: Obviously, you have studied so many coins. Do you have a favourite coin or a favourite type?

Frank: I suppose the obvious thing would be individual coins or small groups of coins that I have published a separate book monograph about. Obviously, I found them fascinating enough to spend the time to write about them. I have written a book about the coins of the first independent Greek Kings of Bactria, which is now Afghanistan; I find those coins fascinating. Then there are the coins of Alexander the Great, particularly these medallions that show scenes of battle with elephants and chariots and so forth. It was a real challenge to try to interpret what those were all about. Sometimes it is a coin that is so unique and so extraordinary that it is still wondered whether it is a genuine coin. There is a god medallion of Alexander, for example, that now noisemakers are divided in their opinions about. If it is genuine, if this coin was minted by Alexander, it proves beyond a shadow of a doubt that this man believed and insisted that everyone see him as the living embodiment of Zeus as a God. I did not find any coins or groups of coins in my study to which I would never give a second look. There is something about almost every coin that is worth looking into more carefully, but there are a few that stand out in my mind.

Kelly: Is there much debate about many coins that are falsified?

Frank: Of course. It is a huge problem because we want to trust our evidence and we have to develop all sorts of means by which we test the authenticity of a coin. Sometimes it is straightforward; in the best of all possible worlds, we are studying coins that came out of a controlled archaeological excavation, they were recorded, photographed, and studied. There is a chain of possession all the way through. But the vast majority of coins are not found in that kind of context. They come out of ploughed fields, they come out of hoards that are discovered by metal detectors, and so forth. In some cases, those coins are reliably passed into the hands of academics, but the majority are not. So, when you come across a coin that is unique and there is no other example like it anywhere in the world, but we cannot be sure exactly who found it, where and when, then we have to be more careful with how much we burden that coin with historical weight. It is a problem. Most people think counterfeit coins are a problem for coin collectors who are investing money and do not want to get burned in the process, but it is a torment for academics, especially because we want to present evidence that is genuine.

Kelly: It makes me think that archaeologists before our archaeologists now just did not put the same importance on provenance. Then you have so much less to work with when it comes to at what point it was buried. It must be such a difficult thing to work through.

Frank: Even now, there are many archaeologists, of course, who see a coin as no more than a chronological marker. I have talked to archaeologists and been with archaeologists who clean this coin until there is nothing left but they try to find out the date of this coin. You would not do that with any other artifact coming out of the ground. They would not scrub a pot until there is nothing left on it. More and more, though, archaeologists are becoming aware and employing numismatists on their sites where coins are likely to be found.

Kelly: So it is much more of a collaborative experience now, getting everyone's perspective and professional opinion.

Frank: Absolutely. Archaeologists are aware that coins speak to us about a lot more than just chronology. If you are looking for trade patterns, if you are looking for periods of economic stagnation, you need to be looking at the coins very closely. There is a heightened awareness now. I write in the book about how numismatics and archaeology once originated in the antiquarian period of the Renaissance as essentially the same pursuit. Then, particularly in the 20th century, these two disciplines parted ways, and the great divide between them still exists to some extent. But I try to make some suggestions about how it can be bridged as we go into the future so that archaeologists and numismatists are not as much at odds as they used to be. That has a lot to do with the fact that numismatics still has a strong collector component to it. Academic numismatics often work closely with coin collectors in ways that archaeological purists would say is not acceptable. So, we must find a way to find a practical solution to problems like that.

Kelly: In the end, anyone working on a site, anyone working in archaeology, wants to get as much information as they can out of that site. If that means not working in the old way, not working with collectors, then I guess that is just how they will develop.

Frank: Exactly. There are those who say that if a coin is not completely and thoroughly provenanced, then it cannot be treated in any way as a historical object. Once you have done that, you have eliminated 99.9% of the millions of coins that are available for study today. To go back to my analogy of finding the lost papyrus of Ptolemy's history of Alexander, if it were not properly provenanced, I do not think there would be many classicists who would say, we are not even going to look at it. Of course, we are going to look at that thing very carefully. If it turns out to be genuine, it is irreplaceable. If it is false, let us hope we will find a way to show that definitively and then move on.

I would like to thank all the people along the way for this book. Again, it is my ninth, but in many ways, it is one of my favourites, and it really was possible only because I got excellent training in graduate school. The American Numismatic Society in New York welcomed me as a student some years ago and provided the photographs that make the book, I think, rather special. Students, colleagues, other numismatics, I try to thank as many as I can in the book, but I cannot thank them enough, and I hope that when I get to book 12 and 20 and so forth, I will still be thanking them.

Kelly: Frank, thank you so much for joining me and World History Encyclopedia today!

Frank: Thank you so much.