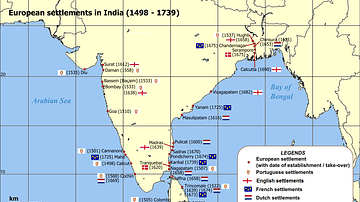

17th-century Dutch East India Company (Vereenigde Oostindische Compagnie or VOC) navigators were the first Europeans to set foot on Australian soil. Although there is a strong theory that the Portuguese explorer, Cristóvão de Mendonça (1475-1532), may have discovered Australia in 1522, the first recorded European landfall was made by the Dutch Willem Janszoon in 1606.

The VOC was a trading company founded by the States-General in the Netherlands on 20 March 1602. The VOC was the merger of six private East India companies and was mainly formed to challenge the Spanish and Portuguese. The States-General granted the VOC a 21-year monopoly over all trade east of the Cape of Good Hope, which led to Dutch dominance of the spice trade in Southeast Asia from 1602-1670.

The European demand for spices such as nutmeg, mace, pepper, and cloves, as well as porcelain and silk from China and Japan, fuelled the emergence of a global trading market that connected Europe with Southeast Asia. The VOC was the first multinational corporation with the powers of a nation-state. It could maintain an army, wage war, negotiate treaties, and settle colonies in the name of the Dutch Republic.

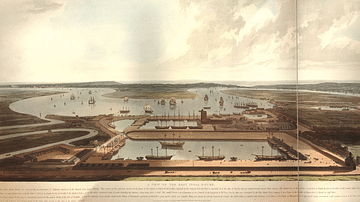

By 1637, the VOC was worth 78 million Dutch guilders (around USD 8.2 trillion), and before its dissolution in 1799, due to corruption and diminishing profits, the company had sent over 4,700 ships to Asia. The VOC ships were bound for the two main spice trading centres in the Indonesian archipelago – the Moluccas and Batavia (Jakarta) – as well as trading posts in Taiwan, Siam (Thailand), and Tonkin (northern Vietnam). Curiously, the vast southern landmass known as New Holland (specifically, the western and northern coastline of Australia) was not the focus of VOC voyages.

Willem Janszoon

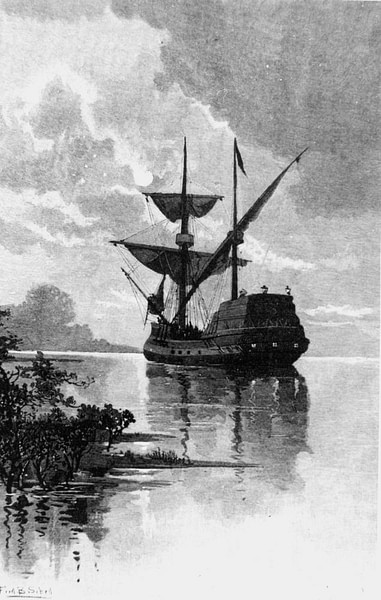

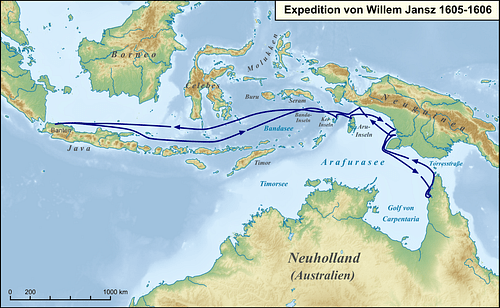

The VOC's connection with the Australian continent began on 26 February 1606 when Willem Janszoon (c. 1570 to c. 1630) made landfall at Pennefather River, near modern-day Weipa on the west coast of the Cape York peninsula (northern Queensland). Janszoon, a mariner from Amsterdam, had been instructed by the VOC to explore the Nova Guinea (New Guinea) coast in search of trading opportunities and gold.

He captained the Duyfken (Little Dove), setting sail from Bantam (northeast coast of Java) in November 1605 to the Kei Islands. He then sailed along the south coast of New Guinea, which he charted before heading southeast, past the entrance to Torres Strait (separating the Cape York Peninsula and New Guinea). Janszoon did not realise it was a strait, and its discovery was left to the Spanish mariner, Luis Váez de Torres (fl. 1605-1607), who successfully sailed through it in 1606 on his way to Manila in the Philippines. The Dufyken reached the Cape York Peninsula, which Janszoon took to be a continuation of southern New Guinea and mapped 250 kilometres (155 mi) of coastline from Weipa to Cape Keer-Weer (Turn-Again or Turn-Around). Heading south, Janszoon sailed into Vliege Bay (now Albatross Bay) – the Dutch word vliege means "fly", suggesting that Janszoon and his crew encountered the annoying Australian blowfly.

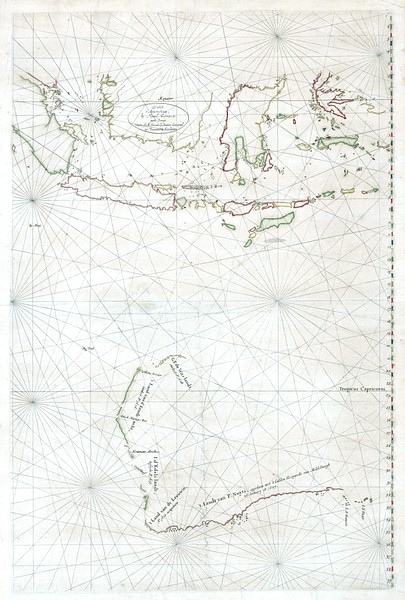

Janszoon's mapping was the first of the Dutch voyages that would chart almost two-thirds of the Australian coastline in the 17th century. The official ship log of the voyage no longer exists, and Janszoon's original map was later lost, but the VOC had it copied when the Duyfken returned to Bantam. This map, known as the 'Duyfken Chart', was discovered in the Austrian National Library in Vienna in 1933. It had been included in the Secret Atlas of the East India Company, which was only used by VOC navigators and not available commercially until its publication in 1670.

The Dutch cartographer, Hessel Gerritsz (c. 1581-1632), bundled many of his maps into the atlas. He was appointed official cartographer of the VOC in 1617, and all ship journals, maps, and charts had to be submitted to him. This gave Gerritsz unprecedented access to the VOC archives, and the earliest map showing the part of Australia charted by the Duyfken was the Gerritsz map of 1622, 'Mar del Sur, Mar Pacifico' (South Sea, Pacific Sea), which authenticated Janszoon's Duyfken as the first Dutch voyage to Australia and confirmed the existence of Terra Australis Incognita (Unknown Southern Land).

The Duyfken Chart shows that Janszoon visited the Kei and Aru Islands (in the Moluccas or Spice Islands) before making landfall at Pennefather River, which he named R. met het Bosch (River with the Bush). Cape Keer-Weer is positioned on the chart as the point where the Dufyken had to turn around after a clash with indigenous peoples, the Wik – the first Aboriginals to have recorded contact with Europeans. Of the Duyfken's 20 crew members, nine were killed in a skirmish, with Janszoon later reporting:

there were nine of them killed by the Heathens, which are man-eaters; so they were constrained to return finding no good to be done there. (quoted in Sharp, 17).

However, the clash most likely occurred because of the attempted abduction of indigenous people. VOC authorities in Batavia gave instructions to crews that followed Janszoon's voyage to capture adults and children so that indigenous languages could be learned for trade purposes. The oral histories of Wik elders have preserved stories of this early encounter with the Dutch.

Janszoon was unaware that he and his crew were the first Europeans to visit Australian shores. He carried out the VOC instructions of exploring and identifying trade opportunities, but he found nothing of value, and after being at sea for nearly four months, the Dufyken headed back to a Dutch base at Banda, south of Ambon, arriving in June 1606. In October 1623, Janszoon was appointed Governor of Banda, but his place in Australian history has been overshadowed by the second Dutch voyage to reach Australian shores – that of Dirk Hartog aboard the Eendracht.

The Brouwer Route & Dirk Hartog

In 1611, Dutch explorer Hendrik Brouwer (c. 1581-1643) devised a shorter route from Europe to Southeast Asia that also avoided the Portuguese Malacca (in Malaysia) and Ternate (in Indonesia). The average voyage of twelve months was halved by taking advantage of the Roaring Forties winds across the southern Indian Ocean before turning northeast to Batavia. The faster route, known as the Brouwer Route, became the preferred Dutch route around the Cape of Good Hope to Southeast Asia, but because chronometers were yet to be introduced, navigational instruments could not calculate longitude very well. Strong westerly winds sometimes forced Dutch ships off course, or they sailed too far east before turning north and were wrecked on the western Australian coast during the 17th century. The Brouwer Route most likely led to the discovery of the western part of Australia by the Dutch in 1616.

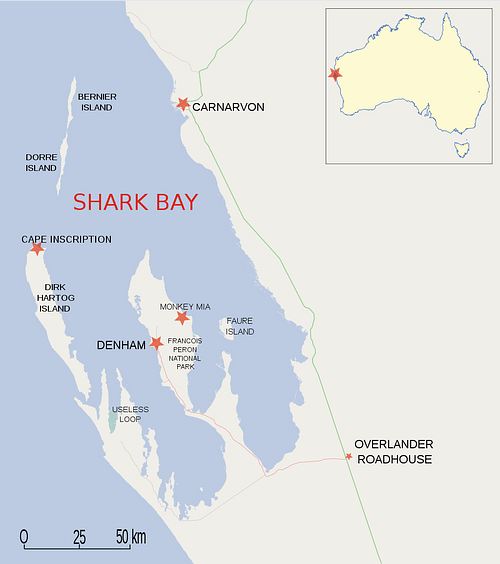

A decade after Janszoon's 1606 visit to the northeastern corner of Australia, Dutch explorer Dirk Hartog (1580-1621) sailed into Shark Bay on Australia's west coast, 850 kilometres (528 mi) north of Perth. His ship, the Eendracht (Concord) at 700 tonnes and with a crew of 200, made landfall on 25 October 1616 at the northern tip of an island in Shark Bay, now known as Dirk Hartog Island.

Dirk Hartog, whose name also appears in history as Dijrck Hartoochz and Dirck Hatichs, was the son of a skipper and a successful private shipping merchant before being commissioned by the VOC in 1616 to sail from Texel (an island northwest of the coast of the Netherlands) to Batavia on a spice trade run. VOC ships would be anchored and provisioned off Texel and await favourable weather conditions. The Eendracht was one of five ships that sailed on 23 January 2016 laden with chests of Dutch guilders.

The Brouwer Route was not enforced by the VOC until 1617, but Dutch ships had increasingly adopted it, sailing east from the Cape of Good Hope across the ocean for 1,000 Dutch miles (7,400 km or 4,598 mi), before heading north to the Sunda Strait between Java and Sumatra. Historical sources are silent on whether Hartog was instructed by the VOC to take the Brouwer Route or decided to do so himself since, before the formal adoption of the route, Dutch ship captains could plot their own course.

Accidental Discovery or Purposeful Exploration?

It is an important historical question: was Hartog's discovery of the west coast of Australia accidental or purposeful exploration? Unfortunately, the Eendracht's logs are not in the VOC archives, but Hartog's journal, crew manifest, and notes would have been submitted back in the Netherlands, as required by the VOC. Hessel Gerritsz used these to create the first chart of the west coast of Australia – a chart that took ten years to produce (1618-1628). Hartog's landing site was noted, and 'Eendrachtsland', one of the earliest names for Australia, was recorded on the chart.

It is likely that Hartog, an experienced sailor, would have known of the Brouwer Route, even though the VOC had not yet endorsed its use. The senior merchant on the Trouw, one of the five ships in the fleet, was Pieter de Carpentier (1586-1659), who would become the fifth Governor-General of the Dutch East Indies in 1627. The command structure of the VOC meant that a senior merchant, or opperkoopman, who was responsible for the profitability of the voyage and recording business on and off a ship, ranked higher than a captain. De Carpentier had sailed the Brouwer Route and was a firm supporter of the VOC's adoption of the faster way to Southeast Asia. The Trouw and the Eendracht had stopped for provisioning at the Cape of Good Hope and remained there for three weeks in August 1616. The Eendracht also had a senior merchant – Gilles Mibais (b. 1571). While it is highly possible that de Carpentier or Mibais, being senior officers, influenced Hartog to take the Brouwer Route, in light of no supporting historical sources, Hartog's discovery of Australia must be viewed as an accidental one.

Hartog spent three days exploring the coast and nearby islands, finding them uninhabited. Before leaving, he acknowledged the Eendracht’s landfall by nailing a flattened pewter plate to a tree. This plate, known to generations of Australian schoolchildren, is called Dirk Hartog's Plate and is kept at the Rijksmuseum in Amsterdam. The place where it was nailed is called Cape Inscription, and Hartog inscribed (translated):

1616 the 25 October is here arrived the ship the Eendracht of Amsterdam, the upper-merchant Gillis Mibais of Liege, skipper Dirck Hatichs of Amsterdam; the 27 ditto set sail again for Bantam, the junior merchant Jan Stins, the first steersman Pieter Dookes van Bill, Anno 1616. (quoted in Van Duivenvoorde, 11).

81 years later, in 1697, the Dutch captain Willem de Vlamingh (1640-1698) found Hartog's badly weathered plate when he landed at Cape Inscription on the De Geelvinck (Yellow Finch) in search of a VOC ship that had run aground on the western Australian coast. Recognising its historic value, he sent the plate to authorities in Batavia.

Curiously, the nailing of the pewter plate did not claim the discovered land for the Dutch. It simply confirmed their arrival and was a 'postal stone' – a visual message left for another ship and its crew – but it became the most tangible proof of an early Dutch presence in Australia 154 years before Captain James Cook (1728-1779) sailed into Botany Bay on 29 April 1770 and claimed Australia for the British.

The Eendracht sailed north as far as North West Cape, charting the coastline before sailing to Bantam. Hartog's late arrival in December 1616 had significant financial implications for the VOC, particularly because he found nothing of interest for Dutch trade. He left Bantam in December 1617 for the Netherlands, the Eendracht carrying silk and benzoin (balsamic resin used in medicine). In 1619, Hartog entered into the service of Elias Trip (c. 1570-1636), a VOC director, and Jacques Nicquet (c. 1571-1642), a merchant and art collector, and sailed to the Adriatic Sea before aiding in the defence of the city of Venice against the Spanish Habsburgs. He returned home, dying in 1621 at the age of 40 from an unknown illness.

After Janszoon's and Hartog's explorations, a series of Dutch ships sailed along the northern, southern, and western coastline of Australia, putting the unknown southern land on the map and surveying 4,000 kilometres (2485 mi) by 1628. In 1619, Frederick de Houtman (1571-1627) sighted and charted the Abrolhos Islands, 80 kilometres (49 mi) west of Geraldton, Western Australia. In 1627, Pieter Nuyts (1598-1655), who became the Dutch ambassador to Japan, entered the Great Australian Bight and charted St Peter and St Francis Islands in what is now called Nuyts Archipelago (South Australia). However, many VOC ships simply ran aground on reefs after being blown off course in the Roaring Forties. In 1628, for example, monsoonal winds drove the Vianen, en route from Batavia to the Netherlands, down along the Pilbara Coast and Barrow Island region of Western Australia.

Before 1770 and Cook's discovery of eastern Australia, 54 European ships sailed into Australian waters, and 42 of those were VOC ships. This might imply that the VOC had a purposeful plan to explore the southern continent, but the company sought profit over settlement. The focus was the lucrative spice trade, which led to establishing trading posts all over Southeast Asia, but the VOC did not set up a trading post in Australia because Dutch voyages brought no rewards in trade, especially when compared to the easy exploitation of the East Indies.

Abel Janszoon Tasman (1603-1659) used the VOC's secret atlas to chart a long section of the western Australian coast before discovering Van Diemen's Land (Tasmania) in 1642. Thanks to Tasman's chief pilot deciding to sail eastward from Mauritius on the 44th parallel rather than the 48th parallel, they made landfall in November 1642 and named the island Anthoonij van Diemenslandt in honour of the Governor-General of the Dutch East Indies, Anthony van Diemen (1593-1645). Tasman had been instructed to find a route between Batavia and South America, and should he come across the great southern land, he was to find out:

…what commodities their country yields, likewise inquiring after gold and silver, whether the latter are by them held in high esteem; making them believe that you are by no means eager for precious metals, you will pretend to hold the same in slight regard, showing them copper, pewter, or lead, and giving them an impression as if the minerals last mentioned were by us set greater value on. (quoted in Salmond, 8).

The VOC desired geographic knowledge and shorter routes that would speed their ships across the Pacific to the riches of South America, particularly Staten Landt (Chile). The last VOC ships to be sent to Australia were the Rijder and the Buis in 1756, and they explored the Gulf of Carpentaria (northern Australia). The 150-year history of VOC ships exploring and charting Australia highlights the VOC's lack of systematic and purposeful exploration of Australia. By 1642, however, the outline of Australia's north and west coasts had been established by VOC voyages – a significant contribution to Australian history.

Unknown European Colonies?

An intriguing aspect of the Dutch discovery and exploration is that around 200 people were marooned when VOC ships sailing the Brouwer Route were wrecked off the Western Australian coastline, or people found themselves unwillingly stranded. Indigenous oral histories refer to Europeans who reached shore cohabiting and integrating with local tribes and becoming the first permanent European presence in Australia.

The first instance of Dutch sailors being unwillingly marooned was in 1629 when two mutineers from the VOC ship Batavia were abandoned at Wittecarra Gully, near Kalbarri, Western Australia. The Batavia had been bound for Batavia and struck Morning Reef (Abrolhos Islands) in June 1629 with 320 people on board. Around 275 survivors made it to shore on nearby islands, but the mutineers attacked and murdered 125 survivors. A rescue ship, the Sardam, marooned the mutineers as punishment. Four skeletons – one of them headless – were found on Beacon Island, part of the Abrolhos Islands, in 2015 and are believed to be those of Batavia survivors.

In 1656, the Vergulde Draeck (Gift Dragon), bound for Batavia, was wrecked off Ledge Point, 105 kilometres (65 mi) north of Perth, Western Australia, and 68 sailors were stranded.

Evidence from these strandings suggests a Dutch influence on indigenous peoples. There are oral histories about Aboriginal people with European features and light or reddish hair and indigenous languages with Dutch-sounding words. For example, 'Arnhem,' used in the name Arnhem Land (Northern Territory), was the name of the VOC vessel Arnhem, which sailed into the Gulf of Carpentaria in 1623 and is also a city in the Netherlands.

In the Perth Gazette in 1834, there was a report that Aboriginals had contact with a group of white people inland of the Swan River said to be descendants of VOC mariners. However, a colony or colonies of Dutch stranded in Australia remains conjecture.

Captain James Cook's landing in Botany Bay in 1770 has eclipsed the fact that the first Europeans to make recorded landfall in Australia were Dutch explorers employed by the VOC. More than half of Australia’s coastline had been charted by the Dutch before Cook discovered eastern Australia and started to shape the complete outline of the southern continent.