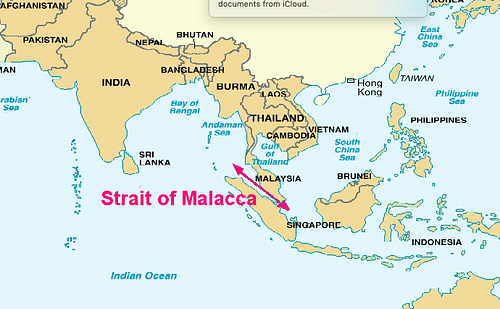

The Portuguese colonised Malacca (modern Melaka) on the southwest coast of the Malay peninsula from 1511 and kept it until 1641 when the Dutch took over. The port controlled the Malay Straits which lead from the Indian Ocean (the Andaman Sea) into the South China Sea and so Malacca acted as both a regional and interregional trade hub.

Geography & Early History

Malacca was founded c. 1400 by the Singaporean ruler Paramesvara (1344 - c. 1424) with a mix of his own followers, settlers from Sumatra (where Paramesvara was originally from) and the indigenous population who lived in what was then merely a fishing village. Its geographic location between the Indian Ocean and the South China Sea permitted it to filter trade between India and China. Traders sailed between the Malay peninsula and the island of Sumatra through the narrow Malacca Straits. This was the shortest sea route between the two areas, but it was a dangerous one with many shallows and shifting sandbanks. Malacca is located at the mouth of the Melaka River and is about 150 kilometres (93 mi) north of Singapore.

Islam reached the region, and the ruler of Malacca, who had himself converted, encouraged Muslim traders. Consequently, Malacca became the most important trade centre in the region where such in-demand commodities as gold, spices, silk, and tea passed through. Merchants from Ming Dynasty China (1368-1644) visited regularly, including the celebrated merchant-explorer Zheng He (c. 1371-1433). The port’s wealth and power permitted it to gain control of most of Malaya and Sumatra, although a naval defence was necessary to keep at bay its neighbour to the north, Siam (Thailand). By the end of the 15th century, less than a hundred years after its foundation, the Sultanate of Malacca boasted an international community of 15,000 traders.

The Portuguese Empire

Ever since 1497-1499, when Vasco da Gama (c. 1469-1524) had sailed around the Cape of Good Hope and shown the possibilities of a maritime route between Europe and Asia, the Portuguese had been busy building an empire. Portuguese Cochin was founded in 1503 and Portuguese Goa was established in 1510, both in India. From the west coast of India, the Portuguese began to search for a base in Malaysia, which might act as a stepping stone to further ports in Southeast Asia and East Asia.

The Portuguese arrived at Malacca in 1509 and were attracted by its fine natural harbour. Two years later, the Portuguese returned in force and a fleet led by Afonso de Albuquerque (1453-1515) captured the port by firing their superior cannons and burning at least 12 ships at anchor in the harbour. A landing party put their firearms to good use and saw off a small army of the sultan’s which included war elephants. The Portuguese were assisted by Coromandel Hindu merchants keen to increase their own trade in the Malayan archipelago. The last sultan of Malacca fled his city.

The geographic and fiscal advantages of Malacca were obvious, as one Portuguese official noted: "Whoever is lord of Malacca has his hand on the throat of Venice" (Cliff, 367), the Venetians being the great rivals to the Portuguese as chief importers of spices to Europe. Albuquerque consolidated his gains by dispatching an ambassador to Thailand in a Chinese junk in order to seal a deal of mutual non-interference. In another example of effective diplomacy, the first Portuguese ships to sail from Malacca to the Spice Islands (see below), included Muslim representatives who were already familiar with the regional trade between Malaysia and Indonesia.

The small Portuguese military presence in the region meant that Malacca was under constant threat from rival city-states, particularly the Sultanate of Acheh based in northern Sumatra. The relations between the many sultanates in this part of Malaysia were another source of instability. Ports like Sarawak, Brunei, Johor, Selangor, and Kedah jostled to control the trade that could only be accessed via the inland rivers whose estuaries they each controlled. Nevertheless, the Portuguese were as ruthless as in other parts of the world in their attempt to monopolise trade by favouring Crown-approved ships, extracting customs duties and port fees from non-European traders, and even sinking ships and confiscating goods of rival merchants.

The Portuguese did manage to dominate the longer, blue-water routes between the continents and subcontinents, but such was the density and scope of the local trade networks, they never got anywhere near being even the major player in the Asian spice trade. Indeed, there was plenty of corruption amongst the Portuguese themselves and the two parallel trades going on continuously: private and Crown trade, with the former not always paying the duties expected.

The Spice Trade

After the Portuguese conquest of Malacca, the Portuguese Empire kept on growing. Hormuz at the mouth of the Persian Gulf followed in 1515, and a fort was established at Colombo in Sri Lanka in 1518. The Portuguese sailed relentlessly eastwards, and c. 1557 Portuguese Macao was established on the coast of southern China near Guangzhou (Canton). Around 1571 the Portuguese gained control of the small fishing port of Nagasaki in Japan. Portuguese Nagasaki became an important doorway into the Japanese market. Malacca thus became one of the central hubs that connected a multitude of Portuguese colonial spokes that connected Portuguese territories in Africa to India to China and Japan. Goods coming into Malacca included spices, rice, textiles, copper, cotton cloth, aromatic woods, animal hides, and opium. In addition, in the 16th century, hundreds of carrack cargo ships left Malacca for Lisbon, carrying precious goods acquired from across the empire such as gold, Ming porcelain, and silk.

Malacca was particularly wealthy thanks above all to the spice trade. Valuable spices used in food preparation across Europe included pepper, ginger, cloves, nutmeg, mace, cinnamon, saffron, anise, zedoary, and cumin. Spices were also added to drinks like wine, crystallised with sugar and eaten as sweets, burned as incense, and used as medicines. Pepper came from India and cinnamon from Sri Lanka, but some of the others like cloves, nutmeg, and mace came from very limited sources, specifically, an archipelago of tiny islands in Indonesia known as the Spice Islands, today the Maluku or Moluccas islands. These islanders did not ship their valuable merchandise themselves but sold it to traders for relatively low-value goods like cotton cloth, dry foodstuffs, and copper. The traders then shipped the spices around the world where they could be exchanged for gold, silver, pearls, gems, and silk. One of the most important of all trade centres for the global spice trade was Malacca, and Portuguese fleets of junks - often with Javanese pilots - sailed every year from Malacca to load up at the Spice Islands.

Society & Christianity

The population of Malacca was a cosmopolitan one, with Malays and indigenous people mixing. There was a strong Chinese presence at Malacca, mostly Chinese merchants living in a quarter of the city known as Chinese Hill. There were, too, a great many merchants from India, Java, Persia, and Arabia. Added to these was the Portuguese community of merchants, permanent and temporary residents, and their mixed-race descendants, Malacca Portuguese. There was, too, a mix of religions, with Muslims, Hindus, Jews, and Christians all living in the colony.

As in other Portuguese colonies, the spread of Christianity was an important goal, even if it came second to making profits. Malacca was given a suffragan or bishop who was a member of the archdiocese headed by Goa. This was made official by a papal bull in 1557 and helped to establish the colony’s new identity along with more commercial factors such as Malacca’s mint, which produced gold and silver coins, not a usual feature of Portuguese colonies. The centre of the European community was represented by St. Paul’s Church, which was built in 1521. The church is now in ruins, but it was once the last resting place of Saint Francis Xavier (aka Francisco de Javier, l. 1505-1552), a celebrated Spanish Jesuit missionary who travelled across East Asia from 1549. The saint’s body was relocated to Goa in 1553.

European Rivals

As with other parts of the Portuguese Empire, the riches available through trade were soon jealously eyed by other European powers. Between 1577 and 1580, the Englishman Francis Drake (c. 1540-1596) made his circumnavigation of the world, which included a stop off at the Spice Islands to take a cargo of cloves. The Dutch arrived in Southeast Asia at the very end of the 16th century, and they soon established a highly efficient trading company, the Dutch East India Company (VOC) based at their regional headquarters at Batavia (modern Jakarta).

The Dutch attacked Malacca City in 1616 and 1629, then, in 1641, and third time lucky, they took over Malacca permanently and ended Portuguese rule there. This prize was followed by many others such as Portuguese Colombo and Portuguese Cochin. The sheer size of the Portuguese Empire and the lack of both manpower and upkeep of fortresses meant that many colonies were easy pickings for rival European powers.

In the 18th century, the British were keen to control the source of trade goods from Southeast Asia they needed for the Chinese market. The British East India Company, the equivalent of the Dutch VOC, represented the interests of the British Crown, and it took over the small island of Penang at the other end of the Malacca Straits in 1786. In 1819, the British took over Singapore, which replaced Malacca as the region’s great trade entrepôt. In the 19th century, Malacca’s economy was mainly driven by its access to inland rubber plantations. In 1824, the British formally acquired Malacca from the Dutch and so came to dominate the entire region with their control of what became known as the Straits Settlements: Malacca, Penang, and Singapore.

Later History

Although silting of the river ensured Malacca never regained its former glory, the Malacca Straits remain one of the busiest stretches of water in the world as modern tanker and container ships continue to carry goods from East to West and vice-versa. Singapore, located at the end of the straits, is today amongst the largest of all the world’s trade hubs. The straits are also being drilled for oil. Melaka, as it is known today, is now part of the state of Malaysia with its capital at Kuala Lumpur, and it still has some visible remains of its colonial past, notably the fort first built by Albuquerque, the ruined St. Paul’s Church, and several examples of Portuguese and Dutch public and domestic colonial architecture. UNESCO has listed Melaka as a World Heritage Site.