Racialized chattel slavery developed in the English colonies of North America between 1640-1660 and was fully institutionalized by 1700. Although slavery was practiced in the New England and Middle colonies, and Massachusetts Bay Colony passed the first slave law in 1641, Virginia pioneered institutionalized slavery and the Virginia Slave Laws, adapted from those of the English colony of Barbados, became the model other colonies drew from in creating their own. Virginia, lacking a model for institutionalized slavery, looked to Barbados, which began importing slaves in large numbers in 1640 to work on the sugarcane plantations.

Jamestown Colony of Virginia had enslaved Native Americans in small numbers by 1610 and the New England Colonies did the same following the Pequot Wars (1636-1638), but this practice was regarded in keeping with the tradition of enslaving prisoners of war. Chattel slavery in which human beings were enslaved who had done nothing to warrant such treatment began in Virginia when a black indentured servant named John Punch was punished with lifelong servitude in 1640 and, following that, laws were passed in the 1660’s which increasingly restricted the rights of the black population (which had developed in the colony beginning in 1619) and then led to the colony’s full participation in the Transatlantic Slave Trade importing more and more Africans to the Americas as slaves.

As the English colonized more land, they imported more slaves to work it – especially in the Southern Colonies of Maryland, Virginia, Carolina, and Georgia which had large tobacco and rice plantations – and each instituted their own slave laws. Maryland, founded in 1632, did not enact slave laws until Virginia’s were firmly in place and by the time Carolina was founded in 1663, Virginia Colony had already institutionalized slavery. Although derived from the Barbadian Slave Code, Virginia Slave Laws were the immediate model for the other colonies (except Carolina, which was settled by Barbadian English planters) and therefore serve as the best model for understanding the development of slavery in Colonial America.

Jamestown & Tobacco

Jamestown was founded in 1607 and struggled to survive for the next three years. The original colonists had been hearing stories of the riches of the New World for years as Spain grew wealthy from their colonies in the West Indies and South and Central America. These colonists arrived in Virginia under the impression that they need do little more than pocket the gold to be found under every other rock and bush in order to become wealthy men of means. When they found this was not the case, they resorted to stealing from the members of the native Powhatan Confederacy who retaliated by containing them within their stockade and, finally, through the first of the Anglo-Powhatan Wars (1610-1614) which resulted in, among other things, the first recorded enslavement of Native Americans in 1610.

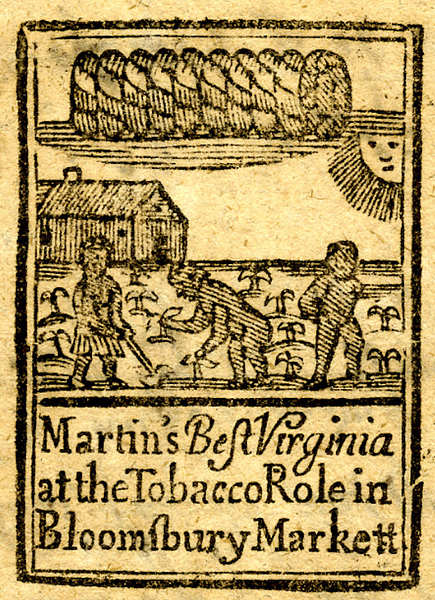

That same year, a ship brought the merchant John Rolfe (l. 1585-1622) to the colony carrying hybrid tobacco seeds. Tobacco had been successfully cultivated by the Spanish in their southern colonies and was already recognized as a profitable cash crop, but the Spanish closely guarded the seeds and plants of their Nicotiana tabacum, quite popular in the European market, and the colonists of Jamestown had, thus far, only been able to attempt cultivation of the rougher Nicotiana rustica used by the natives of North America. Rolfe had acquired Nicotiana tabacum seeds, however, which he blended to create the cash crop that not only saved Jamestown but set the model for large plantations in southern colonies.

Tobacco was a labor-intensive crop, however, requiring a large working class to plant and harvest it. This need was addressed by indentured servants, people who agreed to work for someone else for between 4-7 years in exchange for passage to the New World and room and board for the duration of their service. At the end of their indenture, they were given land, usually some tools, and a gun and were free to do as they pleased.

The First Africans & John Punch

The first Africans arrived in Virginia more or less by accident. In 1619, a Dutch ship in need of supplies docked at Jamestown and traded around 20 enslaved Africans to the governor Sir George Yeardley (l. 1587-1627) for necessary provisions. Yeardley is considered by some scholars as Virginia’s first slave owner but there is evidence that these first Africans were treated as indentured servants, not as slaves. Later records make clear that a number of the 1619 Africans became landowners themselves and black indentured servants are recorded as late as 1676 when they took part in Bacon’s Rebellion alongside white indentured servants and African slaves.

The black population in Virginia seems to have been regarded in more or less the same way as the whites until 1640. In that year, a black indentured servant named John Punch left his master’s service before his term was up, citing poor treatment, and two white indentured servants left with him. The three men were captured and returned to face punishment; the two whites had four years added onto their service, but Punch was sentenced to servitude for life. This is the first recorded evidence of an enslaved African in the English colonies and many scholars date the beginning of slavery in America to this event.

Early Slave Laws & Biblical Justification

By 1650, more Africans had been enslaved because there were not enough indentured servants to work the tobacco fields. Enslaved Native Americans knew the land and could easily run off to find freedom with other tribes, but Africans did not have that advantage and so, along with other considerations, became the slave of choice. By 1662, slaves outnumbered indentured servants and sexual relations between white owners and black slaves resulted in mulatto children. In that year, a law was passed declaring the children of black slave women, fathered by whites, the property of the woman’s master:

Whereas some doubts have arisen whether children got by any Englishman upon a negro woman should be slave or free, Be it therefore enacted and declared by this present grand assembly, that all children born in the country shall be held bond or free only according to the condition of the mother, And that if any Christian shall commit fornication with a negro man or woman, he or she so offending shall pay double the fines imposed. (Timeline, 1)

One of the purported goals of English colonization of North America was the Christianization of the natives and, as more Africans were brought to the colonies, some masters engaged in evangelization of their slaves. In 1667, a law was passed declaring that baptism of a slave into Christianity did not exempt them from bondage. One could convert a “heathen slave” to Christianity in the interests of saving his or her immortal soul but that did not change that person’s status as a slave.

The white colonists’ recognition of blacks having an immortal soul may seem at odds with their practice of slavery and regarding them as property, but this problem was solved by an interesting interpretation of a passage in the Book of Genesis 9:18-24. After the Great Flood, Noah and his three sons – Shem, Ham, and Japheth - came out of the ark and Noah planted a vineyard, got drunk, and lay naked outside of his tent. Ham saw his father naked and told his brothers who then respectfully covered their father without looking upon him. When Noah woke, he cursed Ham’s son, Canaan, saying “the lowest of slaves will he be to his brothers” while the children of Shem and Japheth were blessed for their fathers’ act of covering Noah without looking upon, and thereby shaming, him.

As the passage made clear that from Noah and his sons “came all the people who were scattered over the whole earth” (Genesis 9:18) and the Bible was understood as the literal word of God, blacks were cast as Children of Ham who had been cursed by God himself to serve as slaves to whites, the children of Shem and Japheth. This absurd claim, which can in no way be supported by the text itself in any reasonable fashion (the text does not claim Ham was of a different race than his brothers nor that anyone in the story was a white Englishman or a black African), was coupled with other verses picked from the Bible to justify racialized chattel slavery.

Later Slave Laws of the 1660’s

Once the Bible was invoked as justification, any law could be passed with impunity. By 1669 a law had been passed releasing any white master, mistress, or overseer from responsibility in killing a slave. Since slaves were considered property, it was reasoned, and no one would intentionally destroy one’s own property, killing a slave was considered the accidental outcome of discipline, not a deliberate act of murder. By this time, the rights of the free black population were severely restricted, including inheritance rights. When Anthony Johnson, believed to be one of the original Africans from 1619, died in 1670, his lands were given to a white colonist, even though Johnson had children who expected to receive their legal inheritance. This decision was considered legal because, as a black man, Johnson was not considered a citizen of Virginia and so had no right to land ownership; even though, under the laws of indenture, anyone who had completed their service was legally entitled to the land they had worked for.

As more Africans were imported as slaves to the colonies, and more laws were passed restricting the rights of the free black population – who were not allowed to vote even if they were landowners – concerns began to grow over the possibility of rebellion. In some communities, and in colonies such as Carolina, the slave population outnumbered the white colonists sometimes 2-1. After Bacon’s Rebellion in 1676, indentured servitude was discontinued, and more Africans were imported as slaves. In 1680, as the slave population grew, Virginia passed the Insurrection Act prohibiting slaves from gathering in any large numbers for any reason and from arming themselves:

Whereas the frequent meeting of considerable numbers of negro slaves under pretense of feasts and burials is judged of dangerous consequence, for the prevention whereof for the future, Be it enacted…that from and after the publication of this law, it shall not be lawful for any negro or other slave to carry or arm himself with any club, staff, gun, sword, or any other weapon of defense or offense, nor to go or depart from his master’s ground without a certificate from his master, mistress, or overseer, and such permission not to be granted but upon particular and necessary occasions; and every negro or slave so offending, not having a certificate as aforesaid, shall be sent to the constable who is hereby enjoined and required to give said negro twenty lashes on his bare back, well laid on, and so sent home to his said master, mistress, or overseer…and if any negro or other slave shall presume to lift up his hand in opposition against any Christian, shall for every such offense upon due proof made thereof by oath…receive thirty lashes on his bare back well laid on… (Timeline, 1)

In order to prevent white colonists from assisting slaves, interacting with them as equals, or expressing the desire to marry a slave, a law was passed in 1682 mandating a six-month prison sentence and a hefty fine for the white colonist and punishment for the slave. Slaves were further defined as any non-white, non-Christian who arrived in the colonies involuntarily so that people of color who had been conscripted as crew aboard a ship could now be sold as slaves upon reaching Virginia.

Virginia Slave Laws of the Early 1700’s

This law was enlarged upon in 1705 when the Virginia General Assembly declared that any servant who was not a Christian and who accompanied a white master into the country would be considered a slave. These people would be subject to the same laws that applied to slaves including a white colonist’s freedom to kill them for any reason as long as compensation was paid to the master.

In order to further segregate the races, another law of 1705 made it illegal for any minister to preside over a marriage of a white person and one of color:

Be it further enacted, that no minister of the Church of England, or other minister or person whatsoever, within this colony and dominion, shall hereafter wittingly presume to marry a white man with a negro or mulatto woman; or to marry a white woman with a negro or mulatto man, upon pain of forfeiting and paying, for every such marriage, the sum of ten thousand pounds of tobacco; one half to our sovereign lady the Queen..and the other half to the informer. (Timeline, 1)

In order to be convicted of this “crime”, all that was required was a white colonist in good standing with the community to report that they had either seen such a marriage take place or that they had heard a minister speaking favorably of interracial marriage. As with charges of witchcraft in the colonies, anyone so charged was presumed guilty because it was thought that no one would accuse another of so serious an offense without good reason.

Since slaves were considered property and so could not be fined, any that participated in an interracial marriage would be whipped, branded, or disfigured. Slaves who interacted with white colonists without proper deference and humility could also be beaten, whipped, or placed in the stocks and pillories. A slave convicted of attempted rape of a white woman was hanged and all that was required for conviction was the word of the woman or white “witnesses” to the crime.

Throughout the 1720’s these laws became harsher and those regarding free blacks more restrictive. Black merchants, whether native to Virginia or arriving from other colonies, were not allowed to carry weapons and, in the case of those from elsewhere, had any weapons in their possession confiscated. A black servant of a visiting white merchant, even though a professed Christian, was held to the law of 1705 and considered a slave. As such, the servant could be kidnapped and sold elsewhere and the master had no legal recourse because even though the servant was defined as a slave in Virginia, he or she had not entered the colony as “property” and so there had been no theft and, for all the magistrates knew, the individual had simply run off; no compensation was therefore due the merchant. The laws continued in this fashion, becoming even more restrictive, up through the 1750’s.

Conclusion

As noted, Virginia borrowed their model from the English of Barbados who set the standard for the brutal slave policies which appealed to the colonists’ need for a sense of safety. The more restrictive the measures placed on the black population, the less chance there was of their ability to mount a major uprising. Even so, the white colonists of North America experienced the same unyielding psychological discomfort as those in Barbados, as noted by scholar Alan Taylor:

The Barbados planters paid some heavy psychological and physiological prices for their wealth and power. An especially ethnocentric people, the English found it particularly distasteful to dwell among Africans deemed so utterly different in complexion, speech, and culture. With good cause, the planters also suffered recurrent nightmares of slaves rising up to kill in the night. Adopting a siege mentality, the Barbadian planters walled themselves within fortified houses that kept their blacks out. (216)

In this same way, the colonists of Virginia and elsewhere enacted their slave laws as “fortified houses” to protect them from those they had unjustly enslaved. Even though they defended enslavement of the black population through reference to their scripture, they recognized, on some level, that the enslaved were actual human beings with thoughts and feelings as evidenced by the laws themselves which forbade teaching blacks to read, recognized blacks had souls which should be “saved”, understood black families would be upset if sold away from each other, and took measures to prevent the slaves from rising up and demanding their freedom.

The schizophrenic nature of institutionalized slavery demanded that the white colonists regard the black population as justly enslaved people and, by 1750, entirely as property, while at the same time forcing them to recognize the enslaved as human beings who valued their freedom as much as any other people.

Slave revolts began in 1712 and continued, sporadically, throughout the 18th and 19th century, increasing the white colonists’ fear and leading to harsher punishments and further restrictive measures. The New England and Middle colonies abolished slavery by 1850 but the Southern Colonies maintained the institution until they were forced to abandon it after losing the American Civil War (1861-1865) at which time the whites had no choice but to free the slaves and, legally at least, recognize the black population as equal in human dignity to themselves.