Trade in raw materials and manufactured goods in ancient Celtic Europe was vibrant and far-reaching, particularly regarding the centre of the continent where there was a hub of well-established trade routes. As the Celts' territory expanded, so their trade networks encompassed the Mediterranean cultures (Greeks, Etruscans, and Romans), Iberia, and Britain. Typical goods traded by the Celts included salt, slaves, iron, gold, and furs. These things were exchanged in a barter system for wine, amber, fine bronze, and pottery vessels, and scarce materials like ivory, coral, and coloured glass, which could be incorporated into Celtic manufactured goods. Trade also brought with it an exchange of ideas, particularly in the fields of technology, art, and religious practices. So, too, there was an increase in competition for resources that could be traded, which in turn brought an increase in tribal conflicts and fortified redoubts as well as war with, and ultimately conquest by, the Celts' most powerful neighbours, the Romans.

Key Traded Goods

Goods traded between Celtic peoples and exported to neighbouring cultures included:

- salt

- gold

- slaves

- iron

- copper

- textiles

- skins, hides, and furs

- amber (passed on from the Baltic)

Goods imported by the Celts from neighbouring cultures included:

- wine

- ivory

- coral

- raw glass

- silver

- tin

- foodstuffs such as olives and figs.

- manufactured goods like bronze wares, fine pottery, and furniture.

Early Trade: Gift Exchange

Trade with neighbouring tribes and neighbouring cultures likely began with the exchange of prestige items between rulers. An example of such an object which was likely traded between two different cultures is the Gundestrup Cauldron (3rd-1st century BCE). This gilded silver bowl was found in a peat bog in Denmark in 1891 and has puzzled scholars ever since. The designs of the figures on the bowl are clearly inspired by Celtic gods yet the material was not a popular one amongst the artisans of that culture. There are also visual elements which are inspired by Near Eastern art. The bowl may well have been manufactured in the Lower Danube region, specifically Dacia or Thrace (which is today’s Romania and Bulgaria). It may even have been made for a Celtic client, the ideal gift between two friendly rulers. The bowl may then have made its way to Denmark via a secondary trade or even as war booty.

A similar 'how did it get there?' object is the Trichtingen torc, discovered near the town of that name in Germany. Perhaps dating to the 2nd century BCE and made of silver-plated iron, it weighs 6.7 kilos (14.8 lbs) and so was too heavy to be actually worn. The torc’s bovine heads terminals and the quality of the silver-plating suggest it was perhaps originally from Thrace or Persia, or, at least, it was made imitating the style of art prevalent in those locations. On the other hand, some details suggest it was inspired by art prevalent in Gaul. Was this also a diplomatic gift or a payment for goods received?

Whatever the real stories of the Gundestrup Cauldron and Trichtingen Torc, objects like these did not travel on their own, and they illustrate contact between peoples living thousands of miles from each other. Further, from this exchange of single finely-made or otherwise valuable items, a trade proper sprang up where abundant resources in one community were exchanged for those which could not be easily found locally. Archaeological finds attest that trade between the Celtic tribes in what is today southern Germany and the Greek colonies in southern France was going on as early as the 6th century BCE.

Exported Goods

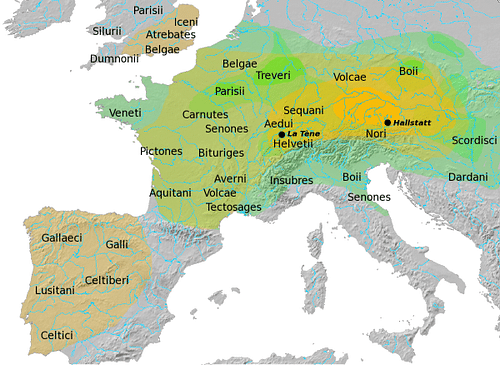

Between the various Celtic tribes themselves, salt and iron seem to have been the most traded of goods. Salt was needed to preserve meat and was particularly abundant in the northern Alps. Here rock salt was extracted from natural briny springs using evaporation and, from the 8th century BCE, also by mining. Salt mines in the Hallstatt area of central Austria are the principal reason for the blossoming of settlements there from the 8th to 6th century BCE. Indeed, the prosperity of the early Celts in central Europe was largely down to their location in the very centre of more ancient trade routes from east to west and north to south. Another factor in a community’s success was its proximity to major rivers like the Rhine, Danube, Seine, and Loire since most goods were transported on water, not land.

Artefacts related to the mining of salt have been preserved by the high content of salt in the soil around Hallstatt. These objects include picks, leather sacks for carrying rocks, and resinous torches. Copper was another precious raw material found in this region and then exported. Salt was also mined in significant quantities at Dürnberg in Austria from c. 600 BCE, but production here and at Hallstatt ended c. 400 BCE. The exhaustion of the salt may well explain the migration of Celts from central to other parts of Europe in the 3rd century BCE, now that the elite had a firmly-established taste for foreign luxury goods.

Iron was a more widely available commodity in Europe than salt, although it required higher technology skills to smelt and work than other metals. It was used to make everything from weapons and tools to cauldrons and jewellery in specialised centres across Europe (although ironworkers in Hungary enjoyed the highest reputation for quality). Unworked iron was typically traded in the form of ingots shaped like a double pyramid or simple rods, each weighing 2 to 9 kg (4 to 20 lbs).

Gold was relatively plentiful in places like Gaul, a point noted by Julius Caesar (100-44 BCE) who, upon observing the Celts' fondness for heavy gold neck torcs, described the region as Gallia aurifera or "gold-bearing Gaul" (Eluere, 160). Gold was extracted from rivers and mines, both opencast and subterranean. Celtic gold prospectors in Gaul are described by the 1st-century BCE writer Diodorus Siculus in his World History:

In Gaul there is plenty of native gold that the inhabitants collect without difficulty or mining. As the rivers rush through their winding bends and dash the foot of mountains they detach lumps of rock and become full of gold dust. People who do this work collect and break-up the dust-bearing rocks, remove the earthy part by repeated washing and melt the rest in furnaces.

(5:27)

Bronze mirrors were a speciality export from southern England in the 1st century BCE and 1st century CE. Sumptuously made, these mirrors often had an openwork handle and the back decorated with intricate designs.

Cloth may well have been traded between local tribes as the Celts were adept at making textiles from wool, linen, bast (a plant fibre), and animal hairs such as those of the badger. Textiles were woven to form patterns or dyed or given decoration using gold thread. Raw wool was exported to neighbouring cultures. Animal skins, hides, and furs like bearskins were exported to other population groups, too.

Finally, slaves, both men and women, were used in Celtic society and as an item for trade, in the latter case the source being those captured in warfare or people who could not pay their debts. Interestingly, the Celtic word for a female slave - cumal - came to be used as a term for a unit of currency. The Romans were especially keen to get their hands on slaves in order to work as labour on their large agricultural estates, especially vineyards.

Imported Goods

In antiquity, the principal sources of European tin were from mines in Cornwall and the West of England, Armorica (northwest France), and northern Spain. The metal was used to make bronze and so tin was shipped to other parts of the continent to such Celtic sites as Mont Lassois in the northeast quarter of France from the 6th century BCE. The treasure-trove of the Vix Burial at the site, which dates to this period, is testimony to the wealth gained from the tin trade.

Red coral was imported (originally extracted from the Tyrrhenian Sea) and used as a high-value decoration for prestige goods like decorated bronze shields and swords in Celtic Britain and elsewhere. Glass, typically in the form of coloured beads or raw ingots was imported in the 6th and 5th century BCE before the Celts learned how to make their own. Silver, in contrast, was not particularly esteemed by the Celts and was limited to coinage from the 3rd century BCE. Amber was imported from the Baltic, although the Celts had no direct contact with peoples there and so it must have been traded via intermediaries. The Celts used amber to make jewellery items like beads and pendants or as a precious inlay material for anything from brooches to furniture. They also traded amber on to the peoples of southern Europe. Finally, horses were traded and came from eastern Europe and the Balkans.

From around 500 BCE, many Celtic tribes became particularly fond of Mediterranean wine. Tens of thousands of Roman amphorae used to store wine have been discovered in Gaul, which date to even before the Roman conquest of the mid-1st century CE. For example, a wreck discovered off the coast of southern France, perhaps once on its way to Marseille and which dates to 75-60 BCE, contained 6,000 amphorae of Italian wine. The Celts purchased their wine mostly with slaves.

Wine was a staple part of the table set at Celtic feasts. These extravagant meals were an ideal opportunity for social display and the Celts seem to have been particularly impressed by fine foreign-made vessels for mixing and pouring wine. Greek drinking cups, gold-trimmed drinking horns, Etruscan bronze kraters, and Roman flagons have all been found in Celtic tombs, illustrating that trade with the Mediterranean cultures was not limited to the wine itself but everything that went with it.

The Consequences of Trade

Trade not only brings the positive outcome of giving access to otherwise scarce resources but it also has secondary consequences. With the people who conduct the trade and often, too, the objects being traded, ideas cross cultures in both directions. In this way, the Celts were exposed to new ideas in metalwork and pottery technology, art, and religious practices. For example, the Celts produced their own coinage from the 3rd century BCE, copying Greek models, although as there was no unified Celtic state of any sort, Celtic coinage was limited as a currency to local use (only its weight in metal had a value) and was largely used for prestige purposes by regional rulers. In another example, Celtic burial practices evolved in the 2nd century BCE following contact with the Mediterranean cultures and so burial in mounds gave way to burials in flat graves or cremation. In art, the Celtic love of complex and twisting vegetal designs which fill every available space likely came from the Near East via contact with the Greeks and Romans. In the other direction, the particular significance the Celts gave to torcs was adopted by the Romans who made it a symbol of valour to be worn on the breastplate of Roman soldiers.

Trade also brings a heightened competition for resources. An increase in the level and violence of competition between Celtic tribes is evidenced in the development from the 2nd century BCE of the fortified sites (and sometimes settlements) known as oppida. An oppidum was typically built at an easily defended location like a hilltop or river bend. Fortifications were built using wood, earth, rubble and stone and designed to ensure the community’s resources could be protected from raids by rival tribes. These safe places then became the ideal location for manufacturing centres and excavations have revealed that countless oppida contained mints to produce coinage and workshops for metalworkers and craftworkers like potters, weavers, and glassmakers. Oppida became trade hubs, indeed many were specifically sited to take advantage of natural resources such as precious metals or established trade routes where such goods as amber passed from one end of Europe to the other.

Finally, trade can invite conquest. When the Romans realised the resources available to the Celts, they had an incentive to end trade and pursue military conquest. As the Roman Empire expanded in Europe from the mid-1st century BCE, so the Celts became an assimilated peoples stripped of their wealth and independence, both political and, eventually, cultural. Trade then replaced warfare as Roman cultural practices spread to new populations and so the demand increased for everything Roman from wine to oil lamps.