Feasts were an important part of ancient Celtic culture which marked important dates in the calendar and community successes. They were, too, an opportunity to display social status and, of course, eat and drink aplenty. Drunkenness and brawling were not an uncommon feature of these events, and sometimes there were even fights to the death over matters of honour such as who should have the right to eat the best cut of meat. Feasts feature prominently in tales from Celtic mythology and even give their name to several celebrated works in the Irish-Celtic cycle of myths.

The Purpose of Feasts

Feasts were an important part of ancient Celtic culture, and items used in them such as spits, cauldrons, and flagons have been excavated from burial sites across Europe. These finds of feast paraphernalia date from the 12th century BCE and into the period of the Roman Empire. Celtic feasts were held to commemorate and celebrate important dates in the religious calendar and to celebrate community successes such as building new defences or constructing a new building. A famous secular feast was the Feast of Tara (feis Temro), held from antiquity to the 6th century CE to celebrate the inauguration of a new Irish High King at Tara in County Meath. Feasts might also celebrate marriages, victories in war, and successful raids against rival neighbouring tribes or commiserate relatives when a loved one had passed to the Otherworld.

Particularly important dates which were honoured with a feast included Imbolc (aka Imbolg) which marked the beginning of spring on 1 February, Beltaine which celebrated the first day of summer on 1 May, Lughnasa (aka Lugnasad) on 1 August which commemorated the start of autumn and the beginning of the harvest, and Samain (aka Samhain) which celebrated the beginning of the Celtic new year on 1 November. The eve of each of these feast days was important as the Celts believed a new day started at dusk. The Celts followed the rhythms of nature and were not tied to specific dates, the dates given above are merely those which were fixed in the Gregorian calendar by Christian writers. It is also interesting to note that the idea of feasts and many of the Celtic festivals themselves remained important after the Christianization of Europe. Some feasts were even transferred into that religion's calendar such as Imbolc which became the feast day of Saint Brigit.

Food & Drink

Naturally, feasts were an opportunity to eat better food than usual and to drink more alcohol. Ancient writers describe Celts as eating at low tables while sitting on a bed of hay. The favoured dishes were meat either roasted on a spit over an open fire or boiled in a stew in a cauldron. Archaeological remains suggest that beef and pork were the most common meat with poultry and game as a supplement. Great hunks of meat were served on bronze, wood, or wicker plates and eaten using the hands and a knife. Cereals were the other main food source as well as seasonal fruit and vegetables.

The Celts were very fond of wine, which they acquired through trade with Mediterranean states, very often exchanging it for slaves captured in war. Tens of thousands of wine amphorae from Italy have been discovered in Gaul, for example, which date to the period before the Roman conquest in the mid-1st century BCE. For the less-privileged, the main drink was either a heavy beer made from fermented malt with hops or a type of mead (fermented honey).

Social Status & Display

Besides having a commemorative function and presenting an opportunity to socialise, feasts were also an occasion for social display. The seating was arranged to reflect each person's status within the community. This was commented on by the Greek author Poseidonius writing his Histories in the 1st century BCE:

…they sit in a circle with the most influential man in the centre whether he be the greatest in warlike skill, nobility of family or wealth. Beside him sits the host and on either side of them the others in order of distinction. Their shield bearers stand behind them while their spearmen are seated on the opposite side and feast in common like their lords.

(quoted in Allen, 16)

The cauldron was an integral part of the feast and had its own special place in Celtic mythology where it was given magical properties and associated with fertility. Once again, cauldrons could be highly decorative and used to display the wealth of the host. The outstanding surviving example of a Celtic cauldron is the c. 1st-century BCE Gundestrup Cauldron found in Denmark, which has high relief panels showing gods, rituals, and animals. The historian B. Cunliffe here summarises the use of cauldrons at Celtic feasts:

The focus of the feast would have been the communal cauldron made of bronze sheets riveted together, with the rim straightened to take two large rings to which were attached chains or ropes so that the cauldron could be suspended over the fire from the roof timbers. To remove the joints of meat from the stew bronze flesh hooks were used.

(68-9)

Decorated drinking horns, finely crafted goblets in gold and silver, bronze flagons, and large wooden tankards encased in bronze were another way to display one's wealth and social status. Many of these items were imported from other cultures such as the Etruscans and Greeks, and so they had extra cachet as 'exotic goods'. Some tankards, such as the famous Trawsfynydd tankard (50 BCE - 75 CE), could hold two litres of liquid and so we can imagine they were for communal drinking where the order of drinkers would have been well-defined.

Fine drinking vessels of all kinds were often buried as a set with the dead. For example, the Kleinaspergle burial Germany, which dates to the 5th century BCE, contained a set of two drinking horns, two wine-mixing vessels, a flagon, and two small drinking cups. Curiously, these sets are often for two drinkers but there is usually only one occupant of the tomb. Perhaps the extras were in anticipation of meeting loved ones in the Otherworld or symbolised the importance of offering hospitality, wherever the deceased ended up.

At feasts, even the food itself was part of the social display as only the most senior guests were allowed the best cuts of meat, for example. The best piece of all was a cut from the thigh and was reserved for the greatest warrior present. If another warrior felt that he was superior, he could claim this piece of meat for himself and so challenge the leader to a fight. Brawls could also break out over more trivial matters, as Poseidonius here describes:

The Celts sometimes engage in single combat at dinner. Assembling in arms they engage in a mock battle drill and mutual thrust and parry. Sometimes wounds are inflicted, and the irritation caused by this may even lead to the killing of the opponent unless they are held back by their friends…When the hindquarters were served up, the bravest hero took the thigh piece; if another man claimed it they stood up and fought in single combat to the death.

(quoted in Allen, 17).

Any stranger turning up to a feast was welcomed and given a seat, and only after they had been refreshed with food and drink were they obliged to give their names and state the purpose of their visit. Gifts were distributed at feasts such as jewellery and other goods made of precious metals or amphorae of wine. Gift-giving was an important expectation which a leader of men had to respect. Typically, these gifts were war booty whose distribution was carefully prescribed according to status.

Entertainment

Besides group singing and general ribaldry, entertainment was provided during feasts by bards whose storytelling, poetry, and skill playing the harp were greatly esteemed in Celtic culture. The bards might sing the praises of men of high status at the feast, as here in a famous episode involving Louernius, chief of the Averni in Gaul:

...when the bard who arrived late at his feast composed a song to the chief's greatness, lamenting his own late arrival, Louernius was sufficiently judicious to throw the bard a bag of gold as he ran behind his chariot and was rewarded by another song based on the theme that even the 'tracks made by his chariot on the earth gave gold and largesse to mankind'.

(Cunliffe, 233)

Feasts in Celtic Mythology

The importance of feasts in Celtic culture is amply illustrated by their appearance in mythology, not only as a colourful setting for key scenes but often as the climax or even title of epic poems. Examples of the latter are Fled Bricrenn ('Briccriu's Feast'), Feis Tighe Chonáin ('Feast of Conán's House'), and Fled Dúin na nGéd ('Feast of Dún na nGéd'). These works were written in the medieval period but they were based on stories from a more ancient oral tradition.

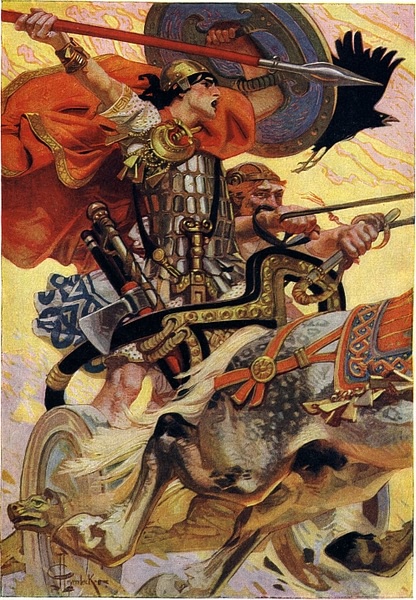

In Briccriu's Feast, named after the host, there is a protracted squabble between several heroes over who should have the champion's portion of meat, in this case, a sumptuous chunk of milk-fed pork. The issue leads to several adventures and is only finally settled when the hero Cú Chulainn gets the better of a terrible giant who intrudes on the feast. Accordingly, Cú Chulainn wins the right to the best cut of pork. Indeed, Cú Chulainn is honoured ever after with always getting the champion's portion at any feast he attends.

In the Feast of Dún na nGéd, there is a memorable scene where two terrible spectres - one male and one female - arrive at a feast and promptly eat up all the food. This situation, the result of a curse, greatly embarrasses Domnall, the legendary king of Ireland, when his capacity to offer hospitality is so rudely eliminated. The situation is serious, and a war follows. The tale is, then, a strong reminder indeed of the importance of feasts in Celtic culture and the necessity to follow strict rules of social conduct.