The Battle of Yarmouk River (or Yarmuk River; also written as the Battle of Jabiya-Yarmuk) was fought over the course of six days, from 15 to 20 August 636 CE, between the Muslim army of the Rashidun Caliphate (632-661 CE), under Khalid ibn al-Walid (d. 642 CE) and the Byzantine legions, under field commander Vahan of Armenia (d. 636 CE). Fighting took place near the Yarmouk River in the Jordan valley, and the battle was a decisive victory for the heavily outnumbered Rashidun army. This victory permanently shifted the dominion in the Levant and Syria from the Byzantine Empire to the Caliphate. Moreover, this was the magnum opus of Khalid, who has been immortalized in legends for his triumph.

Prelude

After the death of the Islamic Prophet Muhammad in 632 CE, his closest confidant, Abu Bakr (r. 632-634 CE) assumed control over the community as the first Caliph of the Rashidun Caliphate (632-661 CE). Having taken the scepter, Abu Bakr faced an open rebellion from all corners of Arabia. Various tribes, who had bowed before the Prophet, declared that their covenant with Muhammad had ended with his life. These renegades were labeled as apostates and were confronted with the full might of Rashidun military in a series of engagements, later styled as the Ridda Wars (632-633 CE).

The most notable Rashidun military leader in this conflict was Khalid ibn al-Walid (l. 585-642 CE), a man cherished by Abu Bakr, despite his flaws, for his unparalleled talent in warfare. He had distinguished himself in warfare, earned the nickname of Saif Allah (the sword of God), and was easily one of the best strategists of his time. He proved to be instrumental in ensuring Rashidun victory against the rebels, all of whom were subdued within a year.

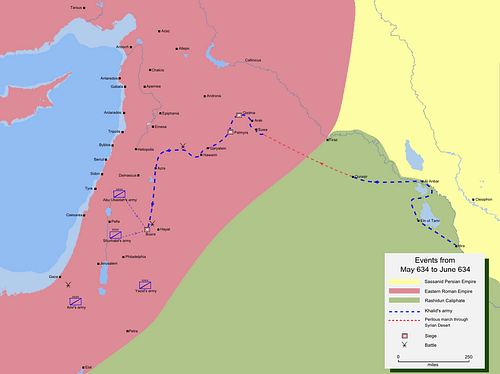

Abu Bakr then launched the expansion of his empire into Iraq and Syria. Khalid's division was sent to the former, where the caliphal army enjoyed much success under him, but the threat of a Byzantine counterattack on the Syrian divisions, who had gained considerable ground, prompted Abu Bakr to send Khalid there. Khalid crossed the barren and trackless desert with his best men, using camels as water reservoirs, and emerged on the fringes of Syria, where after some raiding and conquest, he confronted and defeated a major Byzantine force at Ajnadayn (634 CE).

Abu Bakr, in the meanwhile, died of natural causes and was replaced by Umar (r. 634-644 CE), who stripped Khalid of his command, either because of a personal grudge or because of his harsh personality. In his stead, Abu Ubaidah (l. 583-639 CE), a man renowned for his moral standards, was made the governor of Syria and the commander of the Rashidun corps stationed there. The Muslims continued to engulf the area, Damascus fell in 634 CE, the Byzantine garrison of Palestine was defeated in the battle of Fahl (Pella; 635 CE), and Emesa (Homs) fell in 636 CE, leaving Aleppo only a march away. The Byzantine emperor Heraclius (r. 610-641 CE), determined to rid his land of the Arabs, mustered up a huge force at Antioch to crush the invaders.

Belligerents

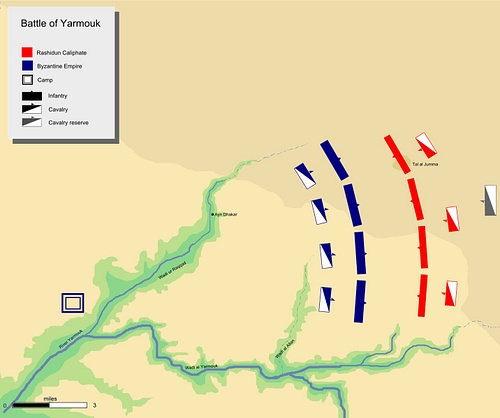

Although Arab chroniclers are notorious for inflating enemy numbers and shrinking their own in comparison, the Muslim army was indeed heavily outnumbered by the Byzantines on this occasion. A huge imperial force, consisting of Greeks, Slavs, Franks, Armenians, Georgians, and Ghassanid (Christian) Arab vassals of Syria, had a cumulative strength of around 40,000.

The Byzantine field commander, Vahan, was an Armenian and had formerly served as the Magister militum per Orientem (Master of the Soldiers in the East; top military commander) of Emesa. Theodore Trithurius, the state treasurer, held the command in theory, but his presence was merely to boost the morale of the troops. Another notable figure among the Byzantine ranks was Jabalah (d. 645 CE), the Ghassanid ruler who had profited much from his alliance with the Byzantines and felt no compunction in serving them against fellow Arabs.

The Rashidun army, originally spread across Palestine, Jordan, Caesarea, and Emesa after their earlier triumphs, was regrouped and withdrawn southwards to the Yarmouk Plateau. There, they were further reinforced by fresh combatants from Medina, the Islamic capital, bringing their numbers up to 20-25,000 on the eve of the battle.

The Battle

Although Khalid was not officially in command, he was highly respected for his skill in battle, and Abu Ubaidah, who lacked such expertise, ceded the command to him. Initially, the Byzantines delayed their advance, wishing to strike simultaneously with the Sassanids whom they had allied with after decades of war. But the ruler of the Sassanian Empire, Yazdegerd III (r. 632-651 CE), required time to prepare, and the Byzantines, ever-impatient to drive the Arabs out, advanced on their own. Khalid, knowing that their position in the north was vulnerable, withdrew his forces all the way to the valley beyond the Yarmouk River. This plateau was an undulating flat land-mass, making it very suitable for the Arab light cavalry, which accounted for a quarter of his army's strength.

- Ghassanid light cavalry, under Jabalah, acted as the vanguard for screening and skirmishing

- The left flank consisted of the Slavic infantry (facing the Muslim right)

- Armenian infantry (under Vahan himself) and European contingents made up the center

- Greek infantry manned the right flank (facing the Muslim left)

- Cavalry divisions, mostly consisting of cataphracts - elite heavy mounted troops, were stationed behind each flank and the two central divisions

Khalid arrayed his 36 infantry regiments in a similar fashion, in front of the Harir River, with 3 light cavalry divisions positioned behind the line, and one larger cavalry reserve under his personal command in the rear. Unlike the multiethnic Byzantine forces, the Arabs were united not only in their nationalist sentiment but also by a common faith. In both armies, infantry consisted of melee fighters and skirmishers (such as archers), and although the Muslims lacked heavy troops, which abounded in the ranks of their foes, they made up for this loss with higher mobility and unparalleled skill in hand-to-hand combat.

…the Muslim right fell back and Byzantine troops reached one or more of the Arab camps. There the retreating Muslim infantry and cavalry were met by their womenfolk who abused them for running away, beat drums, threw stones, and sang songs to shame the men back into battle. The same scenario was enacted slightly later on the Muslims' left flank... (68)

The Byzantines continued to attempt to push through the Muslim ranks for the next two days, and just as Vahan's troops appeared to have made a breakthrough, Khalid would use his reserve to send them on the run. Seeking to buy some respite for his men, the Armenian field commander sued for peace on the fifth day. To the great shock of Abu Ubaidah, who was happily willing to comply, Khalid rejected the offer; the cunning general knew that the time to act was then. The fifth day ended without much fighting, and Khalid, knowing that his foes were demoralized, prepared an all-out assault for the next day, which had been his plan all along.

Surrounded on three fronts, and with no hope of assistance from the cataphracts, the imperial troops began to rout, but unbeknownst to them, their escape had already been cut off. Imperial troops were massacred in their retreat, and many drowned in the river, while some fell to their deaths from steep hills of the valley (many jumped to their deaths to avoid a melee with the Arabs). Khalid all but annihilated his foe and secured a crushing victory, whilst only taking around 4,000 casualties. Vahan either perished in the battle or, according to some, adopted a monastic lifestyle after the pulverizing defeat. Jabalah is said to have defected to the Rashidun side during the climax of the battle, and accepted Islam in 638 CE, only to apostatize later on and escape to Armenia.

Aftermath & Conclusion

With this stunning victory, the Muslims held uncontested power over the Levant and Syria. Jerusalem, a holy city for three monotheistic religions - Judaism, Christianity, and Islam - surrendered personally to the Caliph in 637 CE after receiving assurances of safety. Khalid ibn al-Walid, however, did not receive the prestige that was rightfully his. Umar officially discharged him of duty upon his visit to the region soon after the battle. Though Khalid's morals did not equal Umar's standards (there were some controversies against him), this action was much criticized, for it had been Khalid who saved the Muslim cause from certain doom, but Umar announced that he had done so to show the people that it was God alone who gave them victory.

Khalid retired peacefully (although he is said to have complained to Umar, saying that he was being treated like dirt), died in 642 CE, and was buried in Homs. Though he had been encouraged by many to rebel against Umar, Khalid refused to do so. The Muslims soon engulfed Egypt, parts of North Africa, and several islands in the Mediterranean. On the Sassanian front, a similarly spectacular victory at the Battle of al-Qadisiyya (636 CE) also opened up a similar channel of conquest, swelling the Islamic empire to a titanic size in a matter of mere decades.