The Rashidun Caliphate (632-661 CE) was responsible for setting up the basis of the Islamic empire and expanding its borders beyond the Arabian soil. These leaders were selected by the consent of the people and based on their own merits. They ruled supreme on the lands of Islam as the viceroys of Prophet Muhammad (l. 570-632 CE) and their policies laid the foundation of the style of rule for many future rulers to come. Though the state of the empire was far from being perfect, it was merely the beginning of a long and prosperous period in the history of Eastern civilization. Innovations like centralized government, institutions for administration, public welfare projects, safeguarding the rights of citizens and a general willingness to help people made them quite popular in Arabian history. For their piety and administrative excellence, they are revered by the vast majority of Muslims, and their legacy survives even to this day, in the way Muslims believe that ideal leaders ought to be.

Historical Context

Arabia, at the close of the 6th century CE, was what we would call in modern terms a 'third world country' – if it were a country. But a drastic change was underway as Muhammad, the Prophet of Islam (l. 570-632 CE), took charge. In his 22-year-long mission, as a messenger of Allah (God), Muhammad united most of the fragmented Arabian tribes into one nation.

After the death of the Prophet, his close friend, and companion, Abu Bakr (r. 632-634 CE) established the Rashidun Caliphate (632-661 CE); he was the first of many series of rulers to claim supreme authority over the Islamic world – the caliphs. Abu Bakr was succeeded by Umar (r. 634-644 CE), and he, in turn, was succeeded by Uthman (r. 644-656 CE). Uthman was easily controlled by his tribesmen and this led to his fall from fame; he was murdered in his own house by rebel soldiers.

Ali ibn Abi Talib (r. 656-661 CE), a cousin, and son-in-law of the Prophet, then took the scepter. Ali has been venerated by a group of Muslims called the Shias, who differ from the mainstream Sunnis primarily in that they consider only Ali as the legitimate heir to Muhammad's realm and as the first in a long series of their spiritual leaders or imams.

By the end of the Rashidun Caliphate, the Islamic realm spread far and wide from Egypt and some eastern parts of the North African strip in the west to the whole of the former Sassanian Empire in the east. This was the beginning of a new era – the dawn of the Islamic Caliphates.

Caliph & the Shura

The caliph or Khalifa (in Arabic) literally meant “representative” or “deputy”, as in the representative of the Prophet (Khalifa tul Rasool in Arabic). Abu Bakr, who had been a close companion and friend of Muhammad, laid down the basis of this institution when he took the seat of government, not as an equal to the Prophet, but as his subordinate.

The institution, though divinely inspired, was not based on some instructions laid down in Islam, rather it was a symbolic heritage. The title was not hereditary during the Rashidun period; the caliph was elected by a council of elders called the shura, later on, these men advised the caliph in his actions. No action was carried out without proper counsel, as the Prophet himself had instructed his believers to counsel with others before making decisions. In this manner, the Rashidun government differed from the totalitarian style of rule adopted by emperors or even the later Umayyad Dynasty and the Abbasid Caliphate.

To gain legitimacy, the caliph also needed to receive the bay'ah or the oath of allegiance from his subjects. In this manner, elements of democracy were also inculcated. However, these oaths could also be forced out of those few who refused to give them, once the caliph was widely accepted. The people were also obliged to follow the caliph in all of his actions if they were in accordance with Islam and justice. Abu Bakr made it very clear in his opening sermon after being elected:

I am not the best among you; I need all your advice and all your help. If I do well, support me; if I mistake, counsel me. To tell truth to a person commissioned to rule is faithful allegiance; to conceal it is treason. In my sight, powerful and weak are alike; and to both I wish to render justice. As I obey God and His Prophet, obey me; if I neglect the laws of God and the Prophet, I have no more right to your obedience. (Ali, S. A. 21-22)

Thus a rebel to a lawful caliph was seen as a rebel to Islam itself. Despite enjoying enormous success, the first four caliphs led simple lives and remained humble. The second caliph, Umar, added the phrase Ameer ul-Mu'minin (commander of the faithful) to his title – in later times (Ottoman Empire), this would mean that a caliph could extend his protection to all Muslims, even those living on non-Muslim soil.

Centralized Government

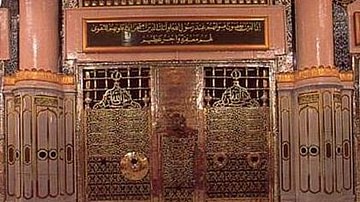

Medina was the capital of the empire and the seat of the caliph, whereas the Mosque of the Prophet was set up as the house of the Parliament – where the council and the caliph would discuss the matters of the state. Later on, during the reign of Caliph Ali, the seat of government was moved to Kufa in Iraq. The name of the caliph was mentioned in the Khutba or Friday sermon in mosques throughout the realm.

Centralized government was a novel addition to the lives of the Arabs, who had formerly lived in a tribal fashion, plagued by centuries-old feuds. After the death of the Prophet, the renegade tribes of Arabia made a wildly strong yet disorganized attempt to fall back to their former tribal lifestyle. This sparked the Ridda Wars or the Wars of Apostasy (632-633 CE). In the course of these wars, one by one, all of these tribes were defeated by the Rashidun armies and the peninsula was reunited once again. A successful reversal at that stage would have been the end of the Arabian Empire.

Rights of Citizens

Generally, the citizens of the Rashidun Caliphate can be divided into two categories: Muslim and non-Muslim. Although the Muslims did enjoy certain privileges reserved for them such as a higher citizenship standard, complete freedom of worship was offered to all people, and the caliph was the spiritual protector of their lives and properties. Jews, Christians, Samaritans, and Zoroastrians were styled as the Ahl al-Kitab or the people of the book, owing to the fact that they too, like Muslims, adhered to a holy scripture – hence full religious tolerance was extended to them.

This tolerance, however, came at a price: it allowed the rulers to extract special taxes (although not heavy) from their non-Muslim subjects. Non-Muslims, living inside Muslim borders were termed as dhimmi or protected people – they were exempt from military duty which was obligatory for all able-bodied Muslim males; but they did compensate via a special tax called jiziya.

Caliph Umar ensured that the conquered people retained the rights to their land and possessions. He took a drastic measure to protect them from harassment, by housing the conquering armies in separate quarters so as to minimize their intermingling with the conquered locals. Special garrison cities were built for this purpose; in Egypt, Fustat was erected, while in Iraq, the cities of Basra and Kufa were constructed. A reversal of this policy took place under his successor Uthman, who, under pressure from his relatives, allowed Muslims to buy land from the conquered natives – the Umayyads, his kinsmen, ended up acquiring quite a lot of property and influence in this manner.

Non-Arab Muslims, those who converted to Islam, were known as Mawali(s) or clients to Arab families (bound by a contract). These people enjoyed certain privileges in the Rashidun period, including exemption from certain taxes that were levied upon non-Muslims. This leniency, however, was revoked by the Umayyad Caliphate – they also made sure that they were kept outside the ruling circle; the barrier, however, was shattered by the Abbasid Dynasty.

Administrative Policies & Introduction of Formal Institutions

Much of the skeletal basis of administration was put in place by the second and the most famous caliph: Umar. His predecessor's brief reign was marked with consistent strife and disorder which he managed to bring under control, but it was up to Umar to make the empire work. His administrative achievements can be summarized as follows:

- Formalization of provinces in conquered lands

- Assignment of governors to said provinces

- Establishment of a strong and independent judiciary system

- Formalization of the state treasury and the establishment of a revenue office to manage finances

- Introduction of pensions for soldiers, instead of dividing up the conquered land among them

- Introduction of a night watch, which was later converted into a municipal guard or police

- Introduction of reforms in the military to ensure discipline and deter cowardice

Even in the time of the Prophet, the empire had been divided into various provinces; keeping true to the way of his patriarch, Umar carved up the conquered lands into several smaller provinces for effective administration. Governors or Ameer(s) were appointed to ensure the welfare of the people in every province. The governors of smaller provinces were termed as Wali or Naib, meaning deputy. These governors answered to the caliph if any abusive treatment befell their people whilst they stood as their sentinels.

The Diwan was established to manage the state revenue, a state treasury – called the Bayt ul Maal – was also formalized for this purpose (it had been established by Abu Bakr). This state treasury also served to provide the caliph with a salary for his services since the caliph could not own a business of his own. General allowances were also given to the Muslims, especially those who were related to the Prophet, early converts, and war veterans (especially from the Battle of Badr, 624 CE - first battle in the history of Islam). This allowance was increased by 25% by Uthman when he assumed the office.

The duty of protecting the people was first handed over to a night watch by Caliph Umar. This force was later converted into a municipal guard (or in modern terms a police force) called the Shurta by Caliph Ali; the captain of this force was titled as Sahib us Shurta. Umar also made several military reforms such as employing officers named Aarif(s) to monitor the troops – breach of discipline, cowardice, and desertion were severely punished.

The conquered land was not divided amongst the troops; conquered peoples paid tax instead. This way Umar ensured stipends and pensions for his troops; pensions were also a novel addition to the Arabian lifestyle. He also limited the intermingling of his soldiers with the locals to prevent the harassment of the latter and the demoralization of the former.

State Revenue

The Diwan or the office of revenue was responsible for handling the state revenue. The currency of the empire was that of the Sassanians with an added inscription "Bismillah" (in the name of Allah) to it; the currency was standardized by the Umayyads. The Islamic Empire, like any other empire of its time, drew its earnings from multiple sources, some permanent and some temporary:

- Zakat or alms payable by all Muslims who possessed sufficient resources

- Kharaj or land tax imposed on non-Muslims (known as tributum soli in the Roman tradition)

- Jiziya or capitation tax, also payable by non-Muslims (known as tributum capitis in the Roman tradition)

- Ushr or customs and excise taxation levied for the first time by Umar on tradable items (which were not for personal use)

- Tributes offered as part of treaties

- Khums or the Maal e Ghanimah; translated to English as the spoils of war

The first three of these sources demand a special explanation. Zakat is one of the basic duties of all Muslims who are in possession of sufficient resources (which are not under their current use). Umar appointed officers to collect these taxes; the money was used to finance the general welfare of poor Muslims, defense of the state, and for paying the salaries of those who collected them. It is pertinent to note that zakat is a reserved form of charity for Muslims only, all other forms of charity can be and are extended to all people, as they have been from the time of the Prophet.

Some cities, tribes, and provinces were exempt from these taxes, as per the order of the caliph (if he felt that there was a legitimate reason to do so). The Maal e Ghanimah or the spoils of war brought a huge influx of wealth to the realm during the reigns of Umar and Uthman, but this gain, although enormous, was temporary.

Development Projects

The vast treasures that filled the coffers of the state were put to good use by constructing multiple buildings, canals, schools, mosques, embankments (on the Tigris and Euphrates – which had been neglected by Kosrau, the Sassanid Shah of Persia) and other developmental projects. Ali shares responsibility in this grand undertaking, as it was he who advised Umar to start these projects.

Umar's primary task was to strengthen trade and improve the peasantry, his method of doing so has been eloquently narrated by historian Syed Ameer Ali:

Egypt, Syria, Irak, and Southern Persia were measured field by field, and the assessment was fixed on a uniform basis. The record of this magnificent cadastral survey forms a veritable “catalog”, which besides giving the area of the lands, describes in detail the quality of the soil, the nature of produce, the character of the holdings, and so forth. (61-62)

This way, Umar ensured that people were not overtaxed, leaving room for growth and improvement.

Conclusion

The Rashidun era was that of the general prosperity of the people. Although the caliphal authority was supreme in theory, this was far from being practical. Since myriads of languages were spoken in the nascent empire, the administration was not universally central.

The Rashidun caliphs also lacked in providing protection to themselves; three of them were murdered in cold blood. Though their administration was not perfect, and possibly many individual officials practiced cruel oppression, the policies they set in place were humanitarian and non-oppressive in nature; it can be argued that the life of a dhimmi in the Rashidun era was better than that of a serf in feudal Europe.

After the death of the fourth Rashidun caliph in 661 CE, the Umayyad Dynasty (661-750 CE) rose to power. These rulers belonged to a pre-Islamic aristocratic background and although they were effective rulers, their policies were far less tolerant than that of the Rashidun caliphs. The Umayyads solidified the caliphal authority and the renegades, who had operated unhindered owing to the leniency of the Rashidun caliphs, now found themselves like flies to wanton boys. They were also responsible for the Arabization of the empire which allowed the centralized authority to prevail over every corner of the empire. In short, Umayyads shifted the direction of the empire from a republican style to an imperial one.

The caliphs of the Rashidun period did not exercise the excess so common in their western and eastern contemporaries. For this simplicity in their lifestyles and their genuine concern for the wellbeing of their people, they are referred to as Khulfa e Rashideen (the rightly guided caliphs), or in English as the Rashidun Caliphate, by the mainstream Sunni Muslims. Shia Muslims revere only one of these four fine men: Ali; since for them, his blood relation with the Prophet supersedes the virtues of his predecessors.