The Ridda Wars or the Wars of Apostasy (632-633 CE) were a series of military engagements between the armies of the Rashidun Caliphate (632-661 CE) and the renegade tribes of Arabia. The rebels had renounced their allegiance with the nascent Islamic Empire after the death of the Islamic Prophet Muhammad (l. 570-632 CE), some tribal leaders had even gone as far as to claim prophethood for themselves, bringing them in conflict with Islam and the Caliphate. Within a year, the Caliphate cemented its control over the whole of Arabia using a potent mixture of active warfare and diplomacy; every sign of rebellion was subdued. With control established at home, Abu Bakr launched successful invasions into Syria and Iraq.

Prelude

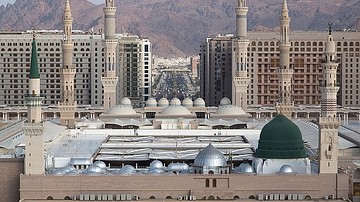

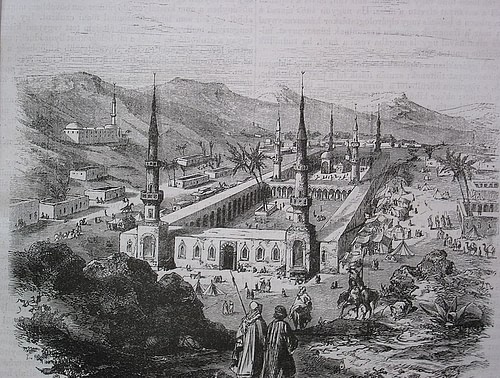

After establishing a base in Medina in 622 CE, the Prophet of Islam and the first sovereign of the Muslim community, Muhammad, unified most of the Arabian tribes under his sway within a decade. A common faith and national sentiment bolstered the cause of the Muslim ummah (community) which soon swept over most of Arabia. Muhammad's death in 632 CE, however, was seen as an opportunity by many to reverse back to their pre-Islamic tribal lifestyle while others sought similar fame by declaring themselves as prophets. In his lifetime, Muhammad had clearly stated that he was the last in a long series of Allah's (God) messengers, and so, for the Muslims, these people were imposters.

The question of government was fiercely debated, while many wished to revert to the home rule system of the pre-Islamic times, others such as Abu Bakr (l. 573-634 CE), a close companion of the Prophet, wished not to let his efforts go to waste. Another group put forward the claim of Ali ibn Abi Talib (l. 601-661 CE), a cousin and son-in-law of the Prophet, for the leadership of the community. This deadlock, which persisted for a while and could have gone either way (centralized government like in the Prophet's time or decentralization of the pre-Islamic period) was broken when Umar ibn al-Khattab (l.584-644 CE), a reputable Muslim, boldly gave his allegiance to Abu Bakr in public and started a snowball event. Abu Bakr, who swiftly gained popular support, proclaimed himself the first Khalifa (Caliph; meaning deputy) of the Prophet and the supreme ruler of Islam, the first of the Rashidun caliphs (as the first four are referred to by Sunni Muslims).

Although the Arabs of the wealthy Hejaz region offered their complete support, Abu Bakr failed to extend his authority over the various Bedouin tribes that inhabited the peninsula. These people detested centralized rule and wished not to be part of a nation in which they had no part in building. Just as he assumed the office, Abu Bakr sent an expeditionary force for some minor raiding in Ghassanid (Byzantine vassal) territory at the fringes of Syria, in retaliation of an earlier defeat at the Battle of Mu'tah (629 CE). As this force departed, the new ruler also had an all-out rebellion at his hands.

Causes of the Rebellion

The rebellious Arabian tribes declared that their pact with Muhammad was of personal nature and that they felt no obligation to serve the new empire; they refused to submit their collection of the zakat (alms payable by all Muslims with certain financial standing) to Medina. These people were branded as apostates, and Abu Bakr soon called a Jihad (holy war – contextually) against them to bring the region to order. The socio-economic and political motives of the Ridda Wars can be summarised as follows:

- Various individuals, each backed by their tribal members, started declaring prophethood, even though Muhammad had clearly declared the finality of his mission and had even predicted the rise of such imposters.

- Autonomous communities wished to retain their independence and refused to be a small part of a larger community, irrespective of the benefits involved. Yemen, for instance, took the first step in declaring itself independent from the Islamic community and the Persian influence of the Sassanian Empire.

- Arabs had lived in tribal fashion for a long time and had no sense of nationalism or national pride; such a sudden change may have been shocking for some.

- A small subset of these rebels were the supporters of Ali, who simply refused to swear allegiance to anyone but him, but due to poor timing, they got mixed with the apostates and rebels.

Although not all of these people had denounced their faith, their rebellion posed an imminent threat to Islam, and hence the use of the term “apostate” in a political sense, in addition to a religious one, is understandable. The most dangerous of these groups were the ones lead by imposter prophets, of whom the strongest was Musaylimah (d. Dec 632 CE), "the Arch Liar" as he is referred to by the Muslims. Abu Bakr, being a close friend and a loyal companion of Muhammad, could not allow his Prophet's faith to be twisted into different versions, and so his decision to primarily employ military action to crush this rebellion may also have had sentimental reasons entwined with practical ones.

Subjugation of the Renegades

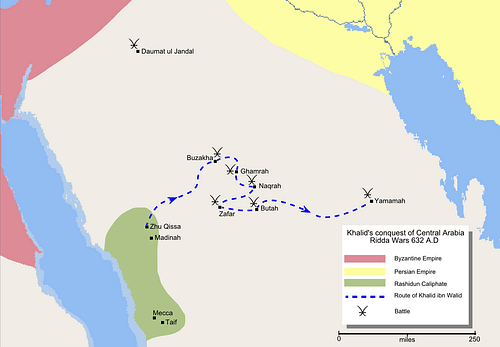

Medina stood as the sole bastion of Islam, just as in the times of the Prophet, only this time there was support from various quarters. Upon the return of Muslim troops from the Ghassanid realm, Abu Bakr rallied his supporters and called upon them to fight for a unified Arabia. Armies gathered under the banner of Jihad were divided into eleven corps, each meant for the subjugation of a particular region. Had the Caliph used a single large army to fight against the disunited tribes one by one, he would have left Medina exposed for his foes to attack, but by engaging them simultaneously, not only did he keep them from striking back but also isolated them.

One after the other, rebellious tribes were subdued, either via the use of arms or diplomacy, which had always been Abu Bakr's strong point, and within a year, the threat had been minimized. Yamama (or al-Yamama) in the Najd province, however, continued to pose a dire threat. Here, Musaylimah of the Bani Hanifa tribe, learning from the mistakes of his contemporaries had allied with another false prophetess named Sajah via marriage and amassed a strong following. Two commanders, Ikrimah and Shuhrabil, one after the other were sent to keep Musaylimah at bay with instructions of not engaging until ordered, both leaders, however, gave in to their rashness and were defeated.

At this stage, when an aura of invincibility surrounded the imposter, Abu Bakr sent forward his best commander. Khalid ibn al-Walid (d. 642 CE) was a loyal subordinate to Abu Bakr and instrumental in securing his dominion over the rogue tribes of the peninsula where he often employed harsh measures to coerce subjugation, for which he was later criticized. His biggest challenge in the war was defeating Musaylimah's forces which outnumbered him vastly, but his tactics never failed him and just as he was about to exhibit, he was no stranger to turning the tide of battle. It had been him in 625 CE, when the Islamic nation of Medina was at war with Mecca, who, as a Meccan cavalry commander, delivered the Muslims a crushing defeat at the Battle of Uhud. His conversion, later on, became a victory for Islam in itself; his military services, extended to the Islamic cause, earned him the title of Saif Allah, meaning the 'sword of God'.

Aftermath & Conclusion

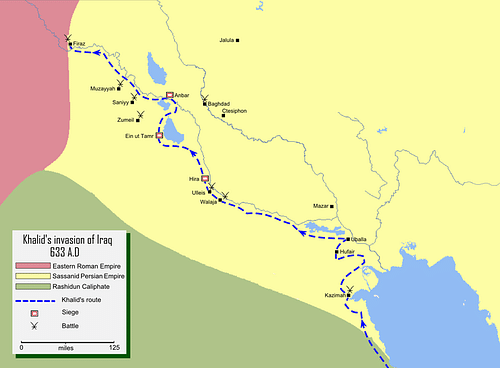

Abu Bakr used a potent mixture of active warfare and diplomacy (by seeking alliances against the rebels) to secure his control over the Arabian Peninsula. Al-Muthanna ibn Haritha, a local Arab chief in the Iraqi region, who had rallied to the caliphal side, began raiding Sassanian territories and informed Abu Bakr of their vulnerability, prompting the caliph to send Khalid to Iraq, where the Rashidun army would enjoy much success.

Unification of the Arabian nation had been Muhammad's mission, and during the Ridda Wars, Abu Bakr ensured its fulfillment. Abu Bakr took prisoners from the subjugated tribes as a guarantee of good conduct but made no attempt to punish them. These people were released when Umar (r. 634-644 CE), his successor, assumed the office. After the war, the society became politically stratified: the supporters of the Caliphate were included in the ruling elite; those who remained neutral were kept out of the ruling circle; the lowest position, however, was of the chastised rebels.

The Ridda Wars saw the blossoming of Abu Bakr's talent, who proved himself a capable leader through his resolute and calm nature. He exploited the disunity of his foes to isolate and subjugate them, and through his acts, secured his position, which became uncontested afterward. The loss of manpower at Yamama, most of whom were huffaz (singular: hafiz, meaning protector; contextually – those who memorize the Quran by heart), prompted Abu Bakr to order the compilation of the Holy Quran, on the behest of Umar. On the morrow of his death in 634 CE, Abu Bakr had left an empire in its cradle, to be further expanded and aggrandized by future rulers.