Germanic influence reigned in the Roman Empire from the end of the 4th century CE through the 5th. Germanic individuals took important posts in the government and the military, and Germanic tribes penetrated ever further into lands that had been Roman for centuries. The Western Roman Empire finally collapsed under these various pressures in 476 CE, chief among them the power of invading Germanic tribes. The Eastern Roman Empire, also referred to as the Byzantine Empire, however, was saved from this destruction by a tribe of Anatolian mountain folk, the Isaurians. Although the Roman populace resented the influence of the Isaurians as a foreign takeover and their epoch only lasted for approximately 40 years, the Isaurians changed the Byzantine world forever by surmounting the Germanic influence that had contributed to the fall of the Western Roman Empire.

Germanic Influence in the West

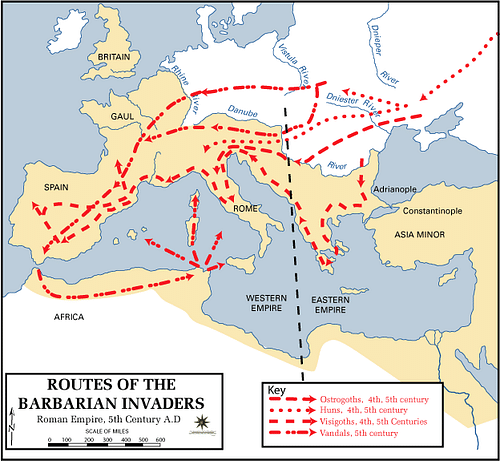

Although Germans had resided inside Roman borders for centuries, the movement of Germanic peoples into the Roman Empire began in earnest toward the end of the 4th century CE. Pushed onward by the Huns, these migrants settled inside the Western Roman Empire. Visigoths settled in southern Spain, the Vandals conquered in North Africa, and other peoples such as the Burgundians and Suevi ended up in other parts of Western Europe. Soon the actual territory that was under the control of the Western Roman emperor was limited to Italy and parts of France.

In addition to external Germanic pressures, the last Western Roman emperors also became ruled by Germanic warlords. The Vandal Stilicho was effectively the ruler of the Western Roman Empire for over a decade after the death of Theodosius I (r. 379-395 CE). The famed Roman general Flavius Aetius, often dubbed the “Last of the Romans,” was almost entirely dependent on Germanic troops to counter the invasions of Attila the Hun. The Suevi prince Ricimer was effectively the kingmaker of the Western Roman Empire between 461 and 472 CE, removing any overly ambitious or competent emperors. The complete grip of the Germanic tribes over the Western Roman Empire was an element in its downfall.

Germanic Influence in the East

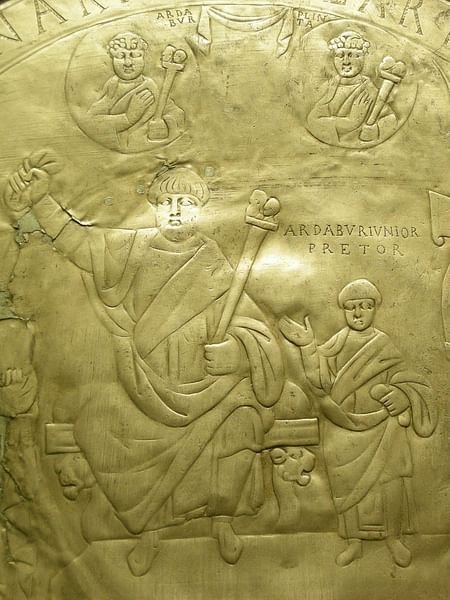

The Byzantine Empire, like the Western Roman Empire, experienced an increase in Germanic importance and influence in the army in the 4th and 5th centuries CE. Connected to this increase was a rise in Germanic influence in the political sphere. Aspar, a powerful Alan general in the Byzantine Empire, was content to be a kingmaker since his own Germanic blood and Arian Christian religion, different than the vast majority of the population, effectively barred him from the imperial throne. Aspar supported one of his own soldiers, Leo, in becoming emperor, hoping that Leo would easily acquiesce to the increasing Germanic tide within the Roman state.

Rise of the Isaurians

Leo I (r. 457-474 CE), however, was anything but servile. He saw the danger of the Germanic forces within the state and wished to limit their extensive influence. For this purpose, Leo needed a replacement for the heavily Germanic army. He looked to the east, to a group of people settled in the Taurus Mountains in modern-day southern Turkey: the Isaurians. The Isaurians were a rough, fierce mountain folk from the wilds of Anatolia that had only partially integrated into the Byzantine Empire. The now emperor supported the Isaurians and even married his daughter Ariadne to one of the leading Isaurian chieftains, Tarasicodissa Rousoumbladotes, later known as the much simpler, and less foreign, Zeno.

Over the next nearly decade and a half of Leo's reign, the Isaurian and Germanic factions within the state competed for influence. The Germanic faction suffered a serious blow in prestige from the disastrous failure of Aspar's ally, Basiliscus, in a campaign against the Vandal king Gaiseric in North Africa, despite Basiliscus' huge numerical and financial advantages. In addition, Aspar suffered from extreme unpopularity in Constantinople, which was only worsened when dark plots by Aspar and his sons against Zeno and the Isaurians came to light. Towards the end of 471 CE, Leo took the final step in placing the Isaurians over Germanic influences when he had his imperial guard kill Aspar and other important Germanic leaders. Isaurian swords cut down the reviled Germanic influence and the state was released from a powerful internal foreign influence.

However, external Germanic pressures still remained. Aspar's remaining men joined with the Ostrogoths under Theodoric Strabo and, with the loss of Germanic soldiers after the death of Aspar, easily ravaged Thrace and Macedonia. Meanwhile, the Gepids took the important Byzantine city of Sirmium. Leo was forced under these circumstances to give Strabo the title magister militum, commander of the armies, although Strabo was not let inside Constantinople. The removal of internal Germanic influence was paid for with the subsequent ravages of the Balkans.

Zeno Comes to the Throne

When Leo died three years later in 474 CE, his grandson Leo II (r. 474 CE), the half-Isaurian son of Zeno and Ariadne, succeeded him. Regardless of Leo I's reason for crowning his seven-year-old grandson rather than his mature son-in-law, Zeno soon took power anyway. Since Leo II was just a child, his mother had him make his father Zeno co-emperor. Just nine months later the child emperor died and the Isaurian Zeno (r. 474-491 CE) became sole emperor.

The Isaurians, however, just like the Germans before them, had made themselves wholly unpopular in the capital. The residents of Constantinople resented the gross foreign influence that dictated so much of imperial policy, regardless of whether it was Germanic or Isaurian. To the Byzantines, these were both uncivilized peoples who behaved in an arrogant and undeserved manner and their great influence on Byzantine politics was shameful. The Isaurians were from inside the Byzantine Empire, so it was illogical to call them barbarians in the same sense as the foreign Germanic tribes, but their uncouth and foreign nature, as well as their arrogant and sometimes violent behavior, inevitably aroused great resentment.

Isaurian Against Isaurian

This dislike became centered on the most distinguished Isaurian, Emperor Zeno himself. His mother-in-law, Verina, and her brother, the same Basiliscus that led the disastrous North African campaign during the reign of Leo I, joined forces with a disgruntled Isaurian general, Illus, to take the throne from Zeno. Zeno fled the capital with his wife and went to Isauria itself as a final stronghold. Despite some Isaurian support from Illus against Zeno, Basiliscus almost immediately ordered a massacre of the Isaurians in the capital.

Rather quickly, Basiliscus' religious impiety and general incompetence made him extremely unpopular. In addition, Basiliscus allied himself with Theodoric Strabo and allowed Germanic influence to rise inside Constantinople once again. This led Illus to become disgruntled and switch back over to Zeno's side. Basiliscus' magister militum, seeing the situation fall apart, was easily convinced to declare his support for Zeno and, meeting no resistance, Zeno was back in the capital in August 476 CE, just a month before the fall of the Western Roman Empire. Not long after, Zeno removed Theodoric Strabo from office, reducing Ostrogoth influence at court.

Zeno & the Ostrogoths

After the fall of Aspar, the leading Germanic leader near Byzantium was Theodoric Strabo, the leader of the Ostrogoths. Strabo was a nuisance to Zeno beyond just supporting Basiliscus' rebellion, leading regular raids into the Balkans and even coming within striking distance of Constantinople. Zeno supported a rival Ostrogoth leader, Theodoric the Amal, later known as “the Great,” appointing him magister militum. Theodoric's Ostrogoths lived further inside Byzantine lands, residing in Macedonia, but Zeno convinced them to forfeit their lands for territory out in the border province of Moesia. Zeno's alliance with Theodoric proved short-lived, but Zeno allied himself with both leaders at different points, trying to play the two against each other. But when Strabo died from riding accident, both bands of Ostrogoths proclaimed Theodoric as their chieftain.

The Ostrogoths were still a thorny issue, but Zeno managed to use them for his own ends. Theodoric's forces supported Zeno against Basiliscus. After all of the infighting between the Germanic and Isaurian factions during the days of Leo I, ironically the Isaurian Zeno countered a rebellion by the Isaurian general Illus with the aid of the Germanic Theodoric.

Later, Zeno sent Theodoric to Italy and gave imperial approval to Theodoric to overthrow Odoacer and rule as an imperial representative in Italy. This migration of the Ostrogoths to Italy removed the last important Germanic influence from the Byzantine Empire. Although ethnic relations were important at this time in Roman history, ethnicity was certainly not the only or even necessarily the prevailing factor in decision making, as shown by the relationships between Zeno, Illus, and Theodoric. Maintaining power and authority was at the heart of imperial decisions by all relevant parties at this time, from Aspar to Leo I to Theodoric. A German might have appointed Leo I to the throne, and Zeno might have been an Isaurian, but that did not stop either emperor from supporting the other important group of their time to maintain and increase their hold on imperial power.

Isaurians After Zeno

Zeno was an unpopular emperor at best whose reputation was hardly helped by his less-than-orthodox religious policy, the near constant rebellions, and the fall of the Western Roman Empire. Evagrius Scholasticus, a later historian of this period, provides a scathing review of Zeno as a servile barbarian. Isaurians had been given many of the best positions in the government and their influence was great, but their position would not survive long without Zeno.

When the emperor died in 491 CE, the Byzantines wanted a Roman emperor. Zeno's brother Longinus was ignored in favor of a respectable former court official who became Anastasius I (r. 491-518 CE) and married Zeno's widow, Ariadne. Soon a group of those dissatisfied by Anastasius' rise to power rallied around Longinus, especially those who had benefitted from Zeno's political appointments, although this was by no means exclusively Isaurians. Longinus was sent away to Alexandria in Egypt, but unrest continued in the streets of Constantinople until most Isaurians had left the capital. Anastasius then carried out several military campaigns that destroyed the power of Isaurians and brought a measure of internal peace to the Byzantine Empire.

Although the Isaurians had certainly caused problems in the capital and their attitudes were unbearable to the Byzantine populace, they were not the only source of unrest. Around this same time the so-called circus factions of the Blues and Greens, named after the respective teams they supported in the races in the Hippodrome, created serious disturbance in the capital, as did Anastasius' sympathies with the non-Orthodox Christian Monophysites. Due to the nature of the Isaurians and their connection to the past three emperors, they were seen as natural enemies of Anastasius and potentially dangerous elements in Byzantine politics and the military. After a heyday of nearly 40 years, the Isaurians had fallen from influence and power.

The Isaurian Legacy

The Isaurians are by no means the most famous of peoples that resided within the Roman and later Byzantine empires, but their 40-year epoch was important for the future of the Byzantine Empire. Although the populace of Constantinople considered them foreigners, they were still subjects of the empire, unlike the Germanic invaders from the north. The Isaurians provided a counterbalance to Germanic influences that had already greatly weakened the soon-to-fall Western Roman Empire. Leo I used them as a new core of the imperial army and used their strength to crush the strong Germanic elements that were represented by the powerful Aspar.

If Germanic power had been allowed to continue to grow it is unclear what the future would have held for the Byzantine Empire. However, the Germanic element was completely removed from importance in the Byzantine Empire by Zeno's commission of Theodoric and the Ostrogoths to go to Italy. Isaurians were a strong measure for the destruction of Germanic power, but at the end of the century, the Byzantine Empire was free of foreign influence over its policies, emperors, and people. The Isaurians, in the guise of people and emperor, had defeated and diverted the Germanic threat and perhaps saved the Eastern Roman Empire at Constantinople from the fate of the Western Roman Empire.