The Woolly Mammoth, Mammuthus primigenius, is an extinct herbivore related to elephants who trudged across the steppe-tundras of Eurasia and North America from around 300,000 years ago until their numbers seriously dropped from around 11,000 years ago. A few last stragglers survived into the Holocene on island refuges off the coast of Siberia and Alaska. One of these - Wrangel Island - harboured the last known group of mammoths until around 3,700 years ago.

With their huge, towering bodies, curved tusks, shaggy coats, and thick layers of insulating fat to keep them warm, these beady-eyed foragers are the cover girls and guys of the Pleistocene. Our hunter-gatherer ancestors (and our cousins, the Neanderthals) would probably have agreed – when successfully brought down during what would no doubt have been a risky hunt or a fortunate scavenging trip, these creatures would have provided a fairly decent amount of rich meat, and their bones could be used both to support huts and to create tools and artefacts.

As such, the fact that humans poked their spears into these creatures is often viewed as a crucial factor in the woolly mammoth's extinction. However, this is a mystery that has not been completely unravelled yet; a role also appears to have been played by the changing (warming) climate towards the end of the Pleistocene.

A hairy picture

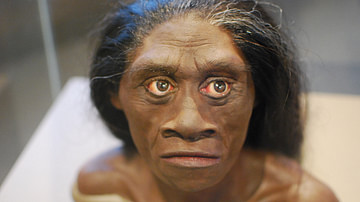

Genetic research conducted during the past decade has shown that the Asian elephant is the woolly mammoth's most closely related living relative. They certainly look similar enough to hint at a connection, but mammoths were clearly slightly better adapted to dealing with frosty circumstances than their tropical sisters.

Having to survive the average winter temperatures of the steppe-tundras that lay between a balmy −30° and a more uncomfortable −50°C meant that mammoths had to develop a suite of features designed to keep as much heat inside their huge bodies as possible. For starters, their ears and tails were small, letting less heat seep out. A comfortably thick layer of subcutaneous fat sat underneath their long and thick fur, which likely varied in colour from blonde and orange to almost black. Their skin and fur was moreover sort of waterproof, which helped improve insulation, and large brown-fat bumps sat just behind the mammoths' necks – ahead of their sloping backs - possibly providing both heat and fat reserves for the harsher parts of winter. Even their blood carried adaptations to minimise heat loss. To top it off, these prehistoric tanks were crowned with high, domed skulls, which sported huge, curved tusks.

Habitat

The woolly mammoth's habitat, referred to as the mammoth steppe, consisted of the arid steppe-tundras spanning all the way from north-western Canada, through Beringia (the exposed and extended Bering Land Bridge), to the west of Europe and as far south as Spain. It looks like mammoths were quite specialised foragers who stuck to their own ecological niche by eating plants killed off by the winter frost, which they may have uncovered from beneath the snow and ice by using their tusks or by trampling.

Sharing the broader prehistoric landscape with these mammoths were other herbivores such as bison, aurochs, the deer family (among which were oversized versions such as Megaloceros or Giant Deer, and the moose genus), as well as a second woolly powerhouse – the woolly rhinoceros. Some of the local predators that were around at the time were prehistoric wolves, as well as hulking cave bears and cave lions, alongside their non-cave counterparts.

Connection with humans

The connection between woolly mammoths and humans stretches beyond that of predator and prey, although it is a good place to start. When one is concerned with feeding a whole band of hungry humans leading active lives, 'the bigger the animal, the better' seems like a good philosophy, and one that certainly tempted people to come up with strategies for bringing these woolly tanks down somehow. You can imagine this would have been no walk in the park, and would probably have required not just weapons but also tactics and cooperation. Direct evidence of mammoth hunting seems to be quite hard to come by, though, and we are not sure exactly with what frequency this happened. We do know that Neanderthals are known to have eaten a fair amount of mammoth meat; they may have focused on hunting large mammals such as mammoths more than Homo Sapiens did.

After a kill, or after a lucky scavenge session, some human groups in central and eastern Europe then used the conveniently big bones to build themselves huts. The Mezinian culture found in present-day Ukraine, for example, used mammoth jaws, long bones and even painted bones arranged in geometric patterns to build the outer walls of their dwellings. In the nearby Danube corridor, mammoth bone accumulations have been found that could arguably have stemmed from early modern humans seasonally gathering there to take advantage of the marshy conditions to throw big mammoth hunting parties. The cool thing is that although the use of mammoth bones as building material would traditionally have been chucked into the lap of early modern humans exclusively, it seems Neanderthals may actually have pioneered this practice; in Ukraine, what looks like a Neanderthal mammoth bone structure has been found.

Going one step further than convenient dwellings, early modern humans (we have no Neanderthal evidence along these lines yet) also produced a bucket-load of tools and figurative objects carved out of mammoth ivory, and even used them as subjects in some of the impressive cave art that stems from the Upper Palaeolithic period in Europe, like in Rouffignac cave and Chauvet cave in France. Practically, the incredibly long mammoth ribs and tusks made excellent projectile points, while figuratively, objects representing various animals and even therianthropic representations mixing animal- and human features were fashioned from mammoth ivory. To top things off, a mammoth ivory flute has been found in southwestern Germany that was skillfully crafted by Aurignacian humans. Although the exact meaning of Palaeolithic cave paintings will always remain shrouded in a degree of mystery, one can imagine woolly mammoths must have left a certain impression on these humans for them to capture their likeness in charcoal on their cave walls.

Extinction

Like many of the other huge mammals (or megafauna) that darted across the Pleistocene plains, the woolly mammoth began to struggle when the climate warmed up after the end of the Last Glacial Maximum - the most recent cold spell, in which the ice sheets reached peak growth between c. 26,500 to c. 19,000 years ago. The academic world loves to argue over whether this warming climate was the mammoths' death sentence, or whether human hunting should largely be held responsible. As with a lot of things in life, the truth probably lies somewhere in the middle, and the final word has not been spoken. That being said, the scenario as it comes to the fore right now is the following.

Mammoths were specialised foragers who relied on their own climatic niche: the cold steppe-tundras. Studies have shown that between c. 42,000 and c. 6,000 years ago, a staggering 90% of areas suitable to mammoths disappeared. As a result, because they were clearly not built to be able to rapidly adapt to new conditions, their numbers plummeted. Of course, inconveniently for the mammoths, from the same point in time early modern humans began to spread across northern Eurasia, where the mammoths' smaller population sizes would have made them much more vulnerable to any degree of human hunting. It looks like it was a perfect storm: the weakening effect of the climate and the changing habitat was enhanced by the effect of human spears. The exact balance is hard to pin down, though. Only a very small number of mammoths managed to dodge these factors for some time and make it into the Holocene, but only because they jumped ship to the safely isolated islands off the Alaskan- and Siberian coasts. The last known mammoth population clung on until around 3,700 years ago on Wrangel Island.

Not quite the end?

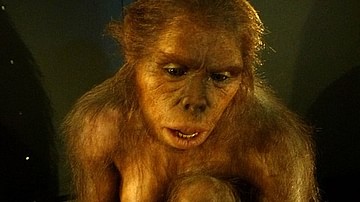

Following through on our usual dose of human megalomania and obsession with 'playing God', this may not be the point of absolute zero for the woolly mammoth. Ever since mammoth remains were found encased in Siberian permafrost, like giant, frozen mummies, with soft tissue and hair astonishingly well-preserved, the world has speculated on the possibility of resurrecting these creatures by using their DNA, in a sort of less scary version of Jurassic Park.

Although looking at the science, life could probably find a way, and researchers say they might be able to use living elephant DNA to fill in the gaps (amphibian DNA to fill in dinosaur gaps, anyone?) within the next couple of years, it obviously raises huge ethical issues. Woollies would be completely out of place in our modern-day built-up world, and would only end up being used as 'tools' to our own benefit, as well as objects for us to gawk at in awe. All in all, it sounds like a terrible idea – let us hope scientists leave these creatures alone and focus instead on uncovering and telling their story as it was, instead of trying to write a self-entitled postscript.