Weetamoo (l. c. 1635-1676, also known as Namumpum, Tatapuanunum, Wattimore, Weetthao) was a female chief of the Pocasset Wampanoag tribe as well as a War Chief in King Philip's War (1675-1678), during which she established herself as a great warrior, and, further was a highly regarded bead-worker/storyteller and ritual dancer.

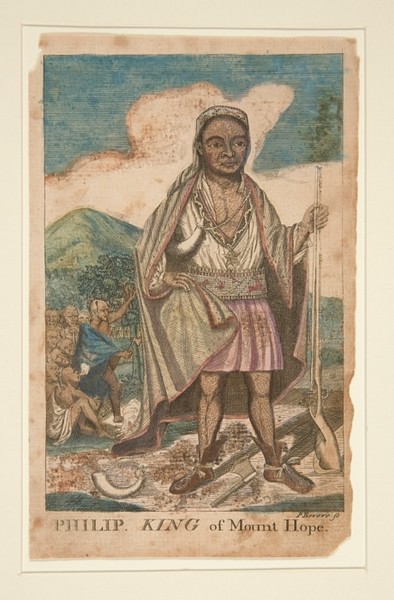

She was the daughter of the great Pocasset chief Corbitant, the wife of Wamsutta (l. c. 1634-1662), chief of the Wampanoag Confederacy 1661-1662, and sister-in-law of Metacomet (also known as King Philip, l. 1638-1676), Wamsutta’s younger brother, who was married to Weetamoo’s sister Wootonekanuske. During King Philip's War, Weetamoo commanded her own forces allied to Philip's, planning and leading attacks on the English colonists.

Weetamoo was married five times and divorced her fourth husband, Petonowit, when he joined the English colonists against Philip in 1675. Her fifth husband, Quinnapin, was the son of Niantic and Narragansett chiefs, and the marriage was a political move to bind those tribes to the Wampanoag Confederacy. She was responsible for a number of the most significant raids on colonial settlements and was feared by the English almost as much as Philip himself.

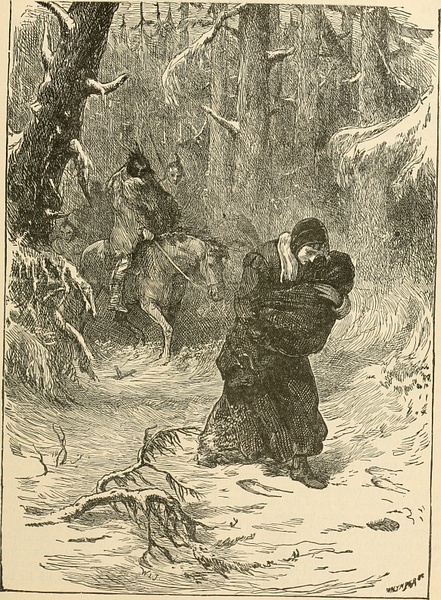

She is best known for the Lancaster Raid of 10 February 1676 during which colonist Mary Rowlandson (l. c. 1637-1711) was taken captive. Rowlandson became Weetamoo's servant and provides the only first-hand description of Weetamoo in the famous narrative of her captivity The Sovereignty of God: Being a Narrative of the Captivity and Restoration of Mrs. Mary Rowlandson.

Weetamoo drowned while crossing a river shortly after King Philip was assassinated in August 1676. Her death was considered such a victory for the colonists that they beheaded her corpse and placed the head on a pole outside the fort at Taunton, Massachusetts. She is still remembered today through place names in Rhode Island although few who visit the parks and camps know who she was or what she stood for; the descendants of her tribe, however, do and continue to honor her memory.

Early Life & Marriage

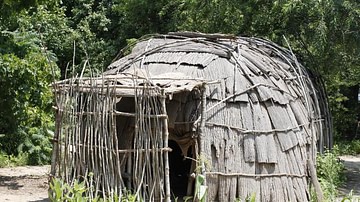

Weetamoo was the daughter of the Pocasset sachem (chief) Corbitant who had no sons and so she was raised as a sunksqua (literally 'elevated woman'), a female chief (though the title also applied to the wife of a chief). Women were responsible for planting, tending, and harvesting crops, building temporary and permanent shelters, making clothes, raising children, and engaging in trade but also took part in council meetings and chose the chief as well as his counselors.

Weetamoo would have no doubt been raised to learn all of these skills but was known as a bead-worker and powerful dancer which would have meant she was held in especially high regard. A bead-worker chose and strung the beads which made wampum belts and sashes – valuable objects among the Native Americans which could serve as currency but also told the story of the tribe – and dance was considered a sacred act, which drew the spirits closer to the mortal realm and answered the peoples' questions or allayed their doubts. As both bead-worker and dancer, Weetamoo would have been among the most highly-respected members of her tribe.

She was given in marriage to the sachem of the Massachusett tribe of Saugus, Chief Winnepurket, when young, but he died soon after. She was then married to Wamsutta, eldest son of Massasoit (l. c. 1581-1661), chief of the Wampanoag Confederacy. Massasoit had helped the pilgrims survive in the New World and had signed the Pilgrim-Wampanoag Peace Treaty with Plymouth’s first governor John Carver (l. 1584-1621) in 1621, pledging mutual support and defense. The treaty was honored throughout Massasoit's lifetime but the English colonists' desire for more and more land strained Native American-Anglo relations after his death in 1661.

Land Deals & Conflicts

No matter how much land the colonists were sold, they always wanted more. Once they had the land under their control, they then made it useless to the natives by allowing livestock to run loose and passing laws which prosecuted the natives for trying to protect their own adjacent lands. Scholar David J. Silverman comments:

Imagine the Natives' frustration when they returned to spring fish runs to find the streams dammed up or fenced off, or cattle grazing in their planting fields, or woods they depended on for fuel and building materials cut down, or their dogs killed for threatening the colonists' sheep. Such incidents mounted with every passing year without resolution…When the Wampanoags killed the trespassing animals, or when their dogs attacked them or when livestock wandered into Indian deer traps, colonists sued for damages. It made Wampanoags wonder why the English valued Indian property so little yet expected their own wandering four-legged private property claims to carry such weight. (266)

Further complicating relations was the change in the attitude of the colonists toward the natives. The first generation of Plymouth colonists had recognized the debt they owed to Massasoit and his people for their help in enabling the settlement to survive, but the sons and daughters of those people cared less and less about honoring Native American interests and rights.

The best example of this is seen in Edward Winslow (l. 1595-1655), among the first colonists of Plymouth who was instrumental in the signing of the peace treaty and later saved Massasoit’s life, as contrasted with his son, Josiah Winslow (l. c. 1628-1680) who cheated the natives out of land and, when his actions were condemned as illegal, used his position as governor to change the laws and enrich himself at the natives' expense.

When Wamsutta became chief after his father's death, Josiah Winslow summoned him to court to answer charges for illegal land sales. Wamsutta had made it clear to the colonists that he wished to maintain the good relations his father had established and would be their ally, but Josiah Winslow accused him of illegal sales as he had sold land to one Richard Smith of Rhode Island – a stranger to the Plymouth Colony – when he should have sold it to Plymouth. Wamsutta was given some refreshments at this interrogation and died shortly afterwards. Weetamoo and King Philip both believed he had been poisoned.

Deception & War

Weetamoo quickly married the chief Quequegunent, son of the Narragansett sunksqua Quaiapen and a nephew of Ninigret, sachem of the Niantic-Narragansett, who, at that time, were already planning hostilities against the English. Quaiapen would later join her forces with King Philip's as one of the greatest leaders of the war. How long Weetamoo was married or what happened to Quequegunent is unknown.

Wamsutta had sold some of Weetamoo's ancestral lands to the English in 1662 which Weetamoo objected to. She appealed to the English for justice in this and was met by a Captain John Stanford and John Archer of the Portsmouth Colony of Rhode Island who convinced her that her remaining lands could be kept safe if she would only sign these over to them; they would protect the lands until Weetamoo decided what she wanted to do with them and then the title would be returned to her. Silverman notes how "obviously, she had faith in these men. Yet they were unworthy of her trust" (267). In 1667, Archer built a house on Weetamoo's land.

When he was confronted by Weetamoo's people, he accused them of attacking him, but the court "uncovered that Archer was the culprit rather than the victim" (Silverman, 267). Archer and Sanford finally confessed that they had tried to cheat Weetamoo out of her lands and that the fraudulent deal had bothered their consciences; just not enough, as Silverman notes, for them to have abandoned it and dealt fairly with her.

Weetamoo had only agreed to Archer's and Sanford's proposal to keep her husband or the new Wampanoag chief, King Philip, from selling her lands out from under her but now she understood she could trust no Englishmen and would have to preserve her lands from sale by native men herself. Wamsutta, after all, had only sold the lands for the good of the people; Archer and Sanford had tried to steal the lands only to enrich themselves. At the same time that she knew she should no longer trust the English, she understood she could not provoke them and so maintained good relations with Josiah Winslow.

Winslow cared little for the natives, however, and saw them as nothing more than obstacles to complete English control of the land. He most likely did poison Wamsutta, and his policies and complete disregard for Native American interests and traditions led directly to the conflict of King Philip's War. In 1675, John Sossamon, formerly King Philip's interpreter but now a Christian and friend of the English, told Winslow that Philip was planning an uprising. Winslow ignored his report because, as he claimed, one could never trust a native. Sossamon was a so-called 'praying Indian' – a convert to Christianity whose loyalties now lay with the colonists – but even this status could not make Winslow trust him.

When Sossamon was found dead shortly after meeting with Winslow in January 1675, King Philip was considered the most likely culprit but, when called to court, denied any involvement, most likely pointing out that Sossamon could have as easily died falling through the ice of the pond he was found in than murdered. Philip was released and no other suspects were sought until, suddenly, in June, Winslow produced eyewitnesses out of nowhere claiming they had seen three of Philip's closest counselors kill Sossamon. The three were arrested and sentenced to be hanged.

By c. 1675 Weetamoo was married to her fourth husband, Petonowit, who was a friend of the English. Weetamoo, as sunksqua, controlled her people, however, and so it was to Weetamoo that Josiah Winslow addressed a letter proposing an alliance once it seemed certain that hostilities would break out between the colonists and the Wampanoags. Scholar James D. Drake writes:

Plymouth governor Josiah Winslow wrote to Weetamoo trying to persuade her to join the United Colonies and their Indian allies. He warned her that Philip "endeavored to engage you and your people with him, by intimations of notorious falsehoods as if we were secretly designing mischief to him and you". Trying to get Weetamoo to support the English, he told her "You shall assuredly reap the fruit of it to your comfort, when he [Philip], by his pride and treachery, hath wrought his own ruin." (97-98)

On 8 June 1675, Winslow hanged Philip's counselors, in direct breach of the 1621 treaty which stipulated that each side would punish their own for offenses. Philip attacked the Swansea Colony on 24 June, and King Philip's War had begun. Weetamoo eventually sided with Philip and divorced Petonowit, who allied with the English, meaning that members of the Pocasset tribe fought on both sides against each other.

Role in King Philip’s War

Weetamoo was now married to Quinnapin, son of Ninigret and cousin of her third husband, and led her troops on raids in support of Philip's troops. She was probably present at the Battle of Bloody Brook on 12 September 1675 when Philip killed 57 of the 79 colonists who were transporting crops and probably led raids on her own in January 1676 when Philip took his army to New York to seek aid from the Mohawks (who, as friends of the English, attacked him and drove him back). She is best known, however, for The Lancaster Raid of 10 February 1676.

The morning of 10 February 1676, the Narragansett, Nipmuc, and Wampanoag attacked the Lancaster settlement, killing many of the colonists and kidnapping others to be held for ransom. Weetamoo and Quinnapin led the Narragansett-Nipmuc contingent and, among others, kidnapped Mary Rowlandson who would later become famous for her narrative relating her time among the natives. Rowlandson describes Weetamoo as a noble woman of strong bearing:

A severe and proud dame she was; bestowing every day in dressing herself near as much time as any of the gentry of the land; powdering her hair and painting her face, going with her necklaces, with jewels in her ears, and bracelets upon her hands. When she had dressed herself, her work was to make girdles of wampum and beads. (The Nineteenth Remove, Hall, 309)

Rowlandson was held for eleven weeks as Weetamoo’s servant before she was ransomed back to her people. Her 1682 book narrating the raid and her time among the natives became a bestseller and is still considered among the best of the so-called "captivity narratives" and a reliable first-hand account of the Native Americans of the Colonial era.

Weetamoo continued to command her troops while also continuing her responsibilities as a bead-worker, making the wampum which told the story of her people and what they were presently enduring. The bead-worker was a storyteller as well as an artisan, and each wampum sash or belt related some aspect of a tribe’s culture, history, mythology, or struggle. Rowlandson’s observation that Weetamoo continued her beadwork during the war is significant testimony to the value of wampum to the Native Americans in preserving their past through stories which could be read through the placement of different colored beads.

Weetamoo continued to mount raids against the English until August 1676 when one of her own people, John Alderman, another 'praying Indian' who had formerly been close to Philip, led the colonists to his camp. Alderman directed a militia under Captain Benjamin Church (l. c. 1639-1718) and Josiah Standish (l. c. 1633-1690) to Mount Hope in modern-day Rhode Island, surprising Philip. Alderman shot him dead and, afterwards, was given his head and hands by Church. Alderman would later show the head to people for a price until he sold it to Plymouth Colony for 30 shillings. The colonists put the head on a pole where it remained for the next 20 years; his body was hacked apart and hung from trees.

Weetamoo, either escaping from the Battle of Mount Hope or coming to assist Philip, drowned as she was crossing a river. Her body floated downstream where it was found by other colonists who treated her as their compatriots had Philip. They mutilated her body, cut off her head, and displayed it outside the fort at Taunton, Massachusetts.

Conclusion

The deaths of Philip and Weetamoo broke the spirit of the Wampanoag and their allies, ending hostilities around Massachusetts and Rhode Island, but the war continued on to the north (present-day Maine) and south until 1678 when the Treaty of Casco was signed and the colonists, along with their native allies, declared themselves victors.

The Native American survivors of the war were sold into slavery, dispersed, absorbed by other tribes, or moved onto reservations. Philip's wife (Weetamoo’s sister), Wootonekanuske, and her son were sold into slavery in the West Indies. Nothing further is known of them but legend has it that Wootonekanuske held her son in her arms aboard the slave ship and jumped overboard once they were at sea, drowning rather than live as slaves. Quinnapin was executed along with any other leaders of Philip’s troops, and even those who had remained neutral during the war or offered assistance to the English were persecuted, had their lands taken, and could be sold as slaves.

Narratives of King Philip's War naturally focus on Philip himself, the causes, and the outcome of the conflict, but there were many notable figures who fought on both sides. Along with Quinnapin, the elder statesman Annawon was executed who had fought alongside Philip and his father. Annawon was the last remaining chief of the old days, and it was he who surrendered Philip's wampum and other possessions to Captain Church as an act of submission to the victors.

Another great leader was Awashonks of the Sakonnet tribe who negotiated with the English to keep her tribe safe and continued to endure English abuse and land theft after the war in the interests of peace and the survival of her people. Among these lesser-known heroes is Weetamoo who also fought for her people in a more direct manner, died for them, and is still remembered by the descendants of her people as a great and noble warrior-chief.