Midgard is the realm of human beings in Norse mythology. The Old Norse word garðr literally means an enclosure (yard), and miðr (middle) refers to its position as a circle with both an interior ocean, and an outer ocean beyond which there lies the dangerous world outside this safe yard, the útgarðr.

The word Midgard has relatives in other Germanic languages, such as Old English (middangeard), Old Saxon (middligard), or Old High German (mittilagart). In Middle English, it evolved towards, or was replaced by, the forms middenerd and middenerthe, where earth follows midden, instead of yard. In any case, the term is most familiar to modern audiences as Middle Earth, massively popularised by Tolkien, himself inspired by the Old English poems of Cynewulf.

The Nine Realms

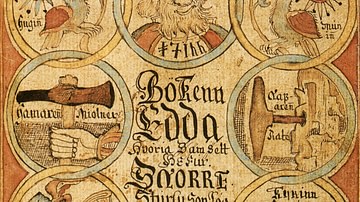

The main sources (the Poetic Edda, a collection of mythological and heroic poems written in the 1200s but of much older age, and the Prose Edda, Snorri Sturluson's attempt to recover the myths to teach poets) talk about the existence of nine realms, nine having a specific magical connotation in Norse myth. The nine realms of Norse cosmology are:

- Miðgarðr (Midgard) – the rampart protecting humans

- Ásgarðr (Asgard) – the gods' enclosure with halls of the Æsir family of gods, like Odin's Valhalla and those of other gods

- Vanaheimr (Vanaheim) – the hall of a second family of gods, the Vanir

- Jǫtunheimr (Jotunheim) – the realm of giants

- Hel – the realm of the afterlife, named after one of Loki's children

- Álfheimr (Alfheim) – the land of the elves

- Svartálfaheimr (Svartalfheim) – the land of the dark elves (the difference between the elves and the dark elves is unclear)

- Muspell – the fiery realm in the creation tale

- Niflheimr (Niflheim) – the watery realm in the creation tale that comes into contact with Muspell and produces ice above the great void, then the first creature, Ymir, appears

Creation & Location of Midgard

The cosmogonic myth shared with Odin by the seeress in the first poem of the Poetic Edda, the Völuspá (Old Norse: Vǫluspá – The Prophecy of the Völva), tells us that the sons of Borr – Odin and his brothers, Vili and Vé – are the ones to fashion this enclosure. Upon killing the first being, Ymir, they split his body into many pieces and thus shape the world. We read in stanza 4 that the sons of Borr lifted up the lands and they shaped the famous Midgard. The sun shone from the south on the stones of a hall, and then the ground was green with leeks. Such details give us a feeling of safety and lushness, which the world of humans was supposed to provide.

We find out exactly how this Middle Earth came into being explicitly from another poem, the Grímnismál (Lay of Grimnir), where Odin, using one of his many names and appearances, engages in a strong monologue filled with mythological lore during his torture at the hands of king Geirröth. In stanza 41, Odin also approaches the topic of how Midgard was shaped. We find out that the happy gods made Midgard out of Ymir's brow for the sons of men. Out of his brain, the mischievous clouds were made. This suggests that we have a strong fence, made by partitioning this giant, that protects humanity, and the name Midgard might refer to the fence itself, rather than the world, although by extension we can think of it as both.

This agrees mostly with Snorri's version in the section of his Edda called Gylfaginning (The Deceiving of King Gylfi), where a legendary Swedish king asks questions about the world of the Æesir, the main family of gods. In chapter 8, when he asks how the earth is arranged, one of the divine beings tells him that the earth is shaped like a disc, and around it lies the deep sea. Along the edge of this sea, they gave lands to the giants to settle, while inside the earth they made a stronghold for people because of the giants' enmity, for which they used Ymir's eyebrows. In other places in Snorri's work, Midgard is referred to more generically, as the dwelling of both humans and gods, as opposed to the land of the giants.

Furthermore, Thor has a strong connection to the world of humans, often being described as the protector of Midgard, which is in harmony with both the Eddic myths and the archaeological evidence pointing out Thor's greater importance for commoners, as his guardian role stands out in comparison to Odin's rather elitist and often deceptive and troublesome nature. The bridge Bilröst, or Bifröst in Snorri's spelling, connects the words of gods and humans, fiery and rainbow-coloured, which will eventually break at Ragnarök.

The Midgard Serpent

A compelling image reminiscent of myths from other cultures such as Apophis from Egyptian mythology is that of Jörmungandr (Jǫrmungandr in Old Norse spelling, simply meaning great monster) or Miðgarðsormr (Midgard wyrm, dragon), the giant serpent encircling the world of humans and dwelling in the outer ocean. A symbol of chaos and destruction, son of Loki with the giantess Angrboda and brother to Fenrir, the wolf who at the end of things at Ragnarök would swallow Odin himself, and to Hel, the keeper of the realm of the dead, Jörmungandr turns out to be Thor's ultimate nemesis. Snorri mentions that when Odin saw what a danger the creature posed, he threw him into the deep sea, but Jörmungandr grew immensely, surrounding all lands and biting his tail.

It is worth mentioning the episode where Thor fishes for the world serpent, of which we have two versions, in both Eddas (the more archaic, more original myths are found in the Poetic Edda). In the poem Hymiskviða (The Poem of Hymir), the host of the gods, Aegir, requires a cauldron large enough to brew ale for everyone. Tyr, the god with the missing limb torn by Fenrir the wolf, knows of such an object at the end of the heavens, where his father Hymir resides. They get there, but Hymir's concubine and Tyr's mother hides them behind the cauldron to save them from Hymir's wrath. Finding out that the friend of humans, Thor, has arrived, enrages Hymir, who nevertheless offers the guests bulls to eat, bound by the rule of hospitality. In the evening, they have to go fishing in the outer ocean to get more food. Using the head of a black bull as bait, Thor catches the Midgard serpent and strikes him in the head with his hammer. At that point, volcanoes erupt and the earth trembles, yet the monster sinks back into the deep waters, for reasons unknown. Thor manages to get the cauldron though, by solving the challenge of breaking the giant's cup, namely right against his head, and then escaping a large army of pursuers.

Snorri's version focuses more on the grudge held against Jörmungandr because of a deception suffered on another journey. In this other story, Thor, Loki and Thor's slave children (enslaved because one of them ate the marrow on the leg of one of the god's resurrecting goats leaving it lame) travel to the hall of the giant Utgarda-Loki, who puts their strengths to the test but uses enchantments to fool them. One of these contests involves Thor attempting to lift the giant's cat, who eventually turns out to be the Midgard serpent.

According to Snorri, Thor enters the realm of giants once more, with no equipment, like a true drengr (very manly warrior). He spends the night at Hymir's, and like in the Poetic Edda, they go fishing. As Thor planned, he catches the wyrm by the jaw, breaking the boat with his feet. Nevertheless, just as he is about to give him the death blow, Hymir cuts the fishing rod, and the serpent sinks back. Although a tad different, Snorri's version probably derives from an old narrative as well, since picture stones such as the Altuna runestone seem to confirm it.

This story, on the one hand, speaks for Thor's close relationship to the human cosmos, Midgard. On the other hand, the Midgard serpent, although an agent of chaos, also works as an element that glues these worlds together, as natural catastrophes occur when he is disturbed. Moreover, he is the counterpart that highlights Thor's protective role. Ultimately, Midgard points to a concept of a border between the inner circle, the civilised world, and the unknown and potentially risky outer world, which lies beyond the fence. United by the same word, garðr, both Asgard and Midgard seem to represent the cosmos, as opposed to the chaos of the jötnar (jǫtnar), the giants. We can compare it to a certain extent to the Greek oikouménē gē, the inhabited world, or in Latin orbis terrarum.