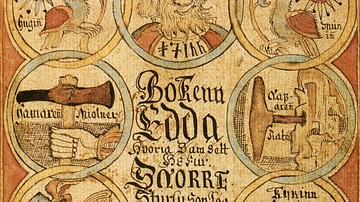

Tyr (Old Norse: Týr) is one of the battle-gods of Norse mythology, according to the main sources on the topic, the literary works called the Eddas. He takes part in two adventures, one involving a monster to whom he sacrifices his hand, and one where he joins Thor to retrieve a cauldron. His name, related to Zeus or Jupiter, evokes a greater significance at some point in history, but unfortunately, we lack enough historical evidence to confirm it.

The One-handed God

Tyr’s main story is the one involving the wolf Fenrir, one of the children of Loki and the giantess Angrboda (Angrboða in Old Norse) - the others being the Midgard serpent (Miðgarðsormr in Old Norse) and the corpse-goddess Hel. The gods, worried about the mischief of this mighty monster, decide to chain him in their realm Asgard, but the wolf seems to break free no matter what kind of fetter they use. This story is told by Snorri, the author of the Prose Edda, a secondary source on Norse myth, but some elements are also featured in the Poetic Edda, the primary source believed to contain texts from the 9th-10th century.

In the Gylfaginning chapter of the book, section 34-35, we find out that Tyr is the only one brave enough to feed the wolf. Due to his strength and wish to brag and achieve fame, Fenrir accepts the gods‘ challenge to bind him with several fetters, all of which he breaks. "And when the æsir [gods] declared they were ready, the wolf shook himself and knocked the fetter so that the fragments flew far away." (The Prose Edda, 28). Fearful of this development, Odin sends Skirnir, Freyr’s servant, to the world of the black elves to find some craftsmen.

In the end, Fenrir is bound by the gods with the fantastic chain Gleipnir, fashioned by the dwarves out of six things: the noise of a cat’s step, the beards of women, the roots of mountains, the nerves of bears, the breath of fishes, and the spittle of birds - all imaginary ingredients, since real ones could not work. Then the gods go to an island called Lyngvi and summon the wolf, show him the silky fetter, claim it is unbreakable but that he would tear it. The wolf seems reluctant, having a hunch that despite its looks of a ribbon it might be made with trickery.

Rather than have his courage questioned, he accepts the challenge of letting himself bound only if someone pledges with their hand in his mouth that it is an act of good faith. Then Tyr comes forward and offers his hand, and while the wolf struggles the chain becomes tougher. The chaining of Fenrir costs the god Tyr his right hand, while the rest of the gods are laughing because they finally manage to catch Fenrir. Then they take the cord and thread it through a stone slab, fasten it in the ground and use another rock as an anchoring peg. The wolf stretches his jaws howling, while the gods thrust a sword into his mouth. His saliva turns into a river, and he would not escape until Ragnarök.

Snorri interprets Tyr’s audacity as a sign of great morality. He describes the god in an earlier section, 25, of Gylfaginning:

He is the bravest and most valiant, and he has great power over victory in battles. It is good for men of action to pray to him. There is a saying that a man is ty-valiant who surpasses other men and does not hesitate. He was so clever that a man who is clever is said to be ty-wise. It is one proof of his bravery that the Æsir were luring Fenriswolf to get the fetter Gleipnir on him, he did not trust them that they would let him go until they placed Tyr's hand in the wolf's mouth as a pledge. And when the Æsir refused to let him go then he bit off the hand at the place that is now called the wolf-joint [wrist], and he is one-handed and he is not considered a promoter of settlements between people. (The Prose Edda, 24-25).

Other References

There are hints at this story in the older sources, the poems of the Poetic Edda. Völuspá (Old Norse: Vǫluspá), the poem where a prophetess summoned by Odin speaks of the beginning and end of the world, mentions the detail of the escape of Fenrir from his trap in stanza 44 as a sign of the apocalypse. The same stanza names one more monster who will howl and cause havoc at Ragnarök, the hound Garm, guardian of the underworld realm of Hel, whom Snorri considers to be the slayer of Tyr.

Tyr makes his appearance in Lokasenna, the exchange of insults (called flyting) between the gods of Asgard, and Loki, the complex character that sometimes joins and sometimes troubles them. Here Tyr gets verbally smashed in stanza 38 after trying to defend Freyr’s noble qualities: "Be silent, Tyr! You could never build friendship between two people / I think of your right hand / bitten off by my son Fenrir" (Hildebrand, 225). Tyr’s inability for peacemaking mirrors his physical handicap. He defends himself by reminding Loki that he also suffered a loss, since his son would be bound until the final battle. Loki continues his barrage of insults in stanza 40, this time resorting to sexual innuendoes: "Be silent, Tyr! / for once your wife had the chance / of a son with me / not a penny I think / were you paid for the wrong / you were not compensated at all, you poor wretch" (Hildebrand, 225). Not getting any compensation for such a misdeed would indeed have represented a significant stain on Tyr’s honour. There is no other reference to Tyr’s wife or son in question.

The other story involving Tyr is told in the poem Hymiskvidha (Old Norse: Hymiskviða), a work of little structure and probably made up of patches from other sources. In a nutshell, the gods wish to hold a feast, and they are trying to figure out where they could find plenty to drink. Ægir, the god of the sea but from the giants‘ family, seems to own a lot of kettles but he only agrees to prepare the mead if they bring him so large a kettle that could boil the drink for all at once. We can speculate this might be an allusion to the sea itself.

Tyr comes into the picture in stanza 5, when he says that he has knowledge of such an object, the kettle of his father Hymir. This detail contradicts Snorri’s opinion in the section Skálskaparmál, fragment 9, where he states that "How shall Tyr be referred to? By calling him the one-handed As and the feeder of the wolf, battle-god, son of Odin." (The Prose Edda, 76). In stanza 8 of Hymiskvidha, Tyr manages to find his grandmother and mother, thus more characters we know nothing about: "The youngster found his grandma / whom he greatly despised / she had nine hundred heads / but a fair one / approached with gold / and the brightly browed / brought her son beer" (Hildebrand, 194).

In some versions of his origin, probably Tyr was mixed race (his father was a giant and his mother a goddess). The story then goes into the direction of another myth, about how Thor catches the world serpent while out fishing with Hymir. The rest of the poem centres around Thor, not Tyr, challenged to break Hymir’s chalice, which he does by slinging it against the giant’s head. The gods then return with the kettle and all can properly indulge in the vast amount of liquor.

Tyr also has a corresponding rune, the t-rune, with possible magical attributes, as suggested in the ballad Sigrdrífumál. Sigrdrifa (victory bringer), another name for the valkyrie Brynhild, teaches the hero Sigurd some rune magic after he rescues her from the shield tower by cutting her mail-coat which was struck to her skin. She says in stanza 6: You shall know the runes of victory / if you want to win / and write them on your sword-hilt / some on the fold / and some on the flat / and you shall call twice on Tyr (Hildebrand 2011, 535). While this could be a religious invocation based on the connection of the rune with Tyr, it might as well just be used for the sake of alliteration.

Was Tyr the Chief God?

Etymology suggests that Tyr might have played a more prominent role before the literary sources and the Viking Age. Týr - proto-Germanic Tiwaz, Old English Tīw, Old High German Ziu - comes from the same Indo-European root as Zeus in Greek, Ju (from Jupiter) in Latin or Dyáus in Sanskrit. The reconstructed name would be dyēus, bearing some association with the skies. If he ever did lead the pantheon, the surviving Norse sources no longer credit him with many attributes or actions. Tyr or Tiwaz gave us the weekday Tuesday, tirsdag in Danish/Norwegian, dies marti in Latin, pointing out to the Roman interpretation (interpretatio romana) of Tyr as Mars, thus focusing on the military attribute. Moreover, we do have Scandinavian place-names related to Tyr, mostly from Denmark, for example Tislund (grove), Tisbjerg (mountain) or Tissø (lake). The limitation to Denmark, from where Angles and Jutes migrated to the west, leaves open the question of Tyr’s worship in earlier centuries.

In Norse sources, the word Tyr simply meaning god could also be used generically in combination with other elements so as to describe a god in a certain way. Odin has many such names, enforcing the idea that he might have based some of his attributes on the original Tyr. For example in the Ballad of Grimnir (Grímnismál in Old Norse), he is called Veratyr (lord of men), Farmatyr (lord of sailors), or Hroptatyr (crier of the gods). The plural form, tívar, occurs in poetry and simply refers to the gods in general. The literary sources, the two Eddas, clearly promote Odin as the chief god, but we should not assume that it had always been the case or that Odin played this part for every Northman throughout the Viking and pre-Viking Age. Thor, for example, appears much more frequently in the archaeological record underlining his predominance among many worshippers.

According to the written sources, Odin clearly emerges at the top of the hierarchy, and all we can do is speculate about Tyr’s personality before the 9th century when the poems of the Poetic Edda were most likely composed and circulated orally.