Mauretania was an ancient kingdom in northwest Africa, encompassing regions of modern-day Morocco and Algeria. Although it shares a name with the modern country of Mauritania, they do not overlap. Ancient Mauretania was named after the Mauri, or Moors, a Berber tribe that inhabited the region.

Mauretania was a highly productive region that produced grain, olives, marble, timber, and livestock. The coasts of Mauretania were famous for producing Tyrian purple, a snail-based red dye that was highly prized in antiquity.

Under Roman rule, it was divided into a western and an eastern territory, named Mauretania Tingitana and Mauretania Caesarensis respectively. These provinces exported food to the Roman Empire during antiquity until they were conquered by the Vandals in the 5th century CE.

Early History

Some of the earliest inhabitants of Mauretania were the Capsian culture, Afro-Asiatic speakers who spread westwards from the area between the Red Sea and the Nubian Nile through the northern Sahara around 9000 BCE. Originally hunter-gatherers, this culture began to domesticate cattle, sheep, and goats by 7000 BCE. These peoples reached Mauretania by the 6th millennium BCE. In addition to raising livestock, they also cultivated some crops like wheat and olives.

Between the 3rd and 2nd millennium BCE, the proto-Berbers began to spread across North Africa and the Sahara, changing the linguistic and cultural landscape. The Mauri, a group of Berber tribes living north of the Sahara, were the primary inhabitants of Mauretania in classical antiquity. The name Mauri might originally derive from a Punic word meaning "westerner". To the east, they were bordered by the Masaesyli and Massylii of Numidia. In later periods, everything west of Numidia and north of the Sahara was called "Mauretania."

The Mauri were organized into clans ruled by chieftains. Some of the Mauri lived a semi-nomadic pastoral lifestyle, producing goods such as wool, hide, leather, milk, and meat. Others had settled into agricultural communities, especially on the coastal plains in the north of the country. By the 4th century BCE, they were united in a tribal federation. The kingdom of Mauretania, ruled by a hereditary monarchy, developed out of this federation. Despite this political development, the clan chieftains may have continued to be important political actors during the Classical period. By the late 3rd century BCE, Mauretania was as powerful as Numidia.

Between the Phoenicians & the Sahara

Mauretania's location enabled its inhabitants to trade with both the Mediterranean and Saharan Africa. The Mauri traded ivory, precious stones, and animal hides to the Phoenicians, who had established port cities like Tingis (Tangier) and Lixus on the coast of Mauretania. Though relatively distant from Carthage, Mauri and Numidians sometimes appeared in the Carthaginian army as mercenaries or allied troops. The Mauri had long-standing cultural and economic ties to the Iberian peninsula and a close relationship with the Phoenician city of Cadiz. Looking south, the Mauri were able to import goods like ostrich eggs and amber from tribes living in the Sahara. They also imported gold, probably from either Spain or West Africa.

Mauretania's sparse population prevented them from urbanizing as rapidly as Numidia, although some Mauretanian towns and cities like Volubilis and Iol were founded during this period. Carthage's empire contracted after its defeat in the Second Punic War (218-201 BCE), and Mauretania was able to take control of many formerly Phoenician ports, including Tingis. Some historians have suggested that contact with the Phoenicians might have influenced the early emergence of an urbanized Mauretanian state. However, the early history of Mauretania is poorly attested to in the historical record, as they were only rarely discussed by Greek and Roman historians.

Interactions with the Roman Republic

Bocchus I (r. c. 110-91 BCE was the father-in-law of King Jugurtha of Numidia (r. 118-105 BCE) and allied with him during the Jugurthine Wars (112-106 BCE). However, Bocchus eventually betrayed Jugurtha and delivered him to the Romans as a prisoner. As a reward, he was given the western part of Numidia in 105 BCE while Rome took the eastern part.

After Bocchus I's death in 91 BCE, his kingdom was divided between two kings, one ruling over his original territory and another over the eastern part of his kingdom which had been annexed from Numidia. In the following years, many Mauretanian kings of the eastern territory would ally with the Romans against Numidia, and Mauretanian troops began to appear as auxiliary troops in the Roman army. However, the western kings were more hostile to Rome and came into conflict with them on several occasions.

Bocchus II and Bogud II were the first Mauretanian kings to mint coins, with Bocchus II's coins bearing Phoenician inscriptions while Bogud's bore Latin. Both kings were at one point allies with Julius Caesar (100-44 BCE) during his civil war with Pompey (106-48 BCE). Bogud II allied with the Caesarian faction during their 47 BCE campaigns in Spain, and in 46 BCE, Bocchus II invaded Numidia to assist Caesar in his war against Juba I (r. 60-46 BCE) and was rewarded with more of Numidia's western territories.

At some point afterwards, the two kings became divided, with Bocchus II supporting the Pompeian faction while Bogud II supported the Caesarians. They took opposite sides again during Mark Antony's civil war with Octavian (32-30 BCE). After Bogud II was killed fighting for Antony in 31 BCE, Bocchus II annexed his part of the kingdom, uniting Mauretania. Upon Bocchus II's death, he bequeathed his kingdom to Rome. Augustus settled colonies of veterans from the Roman army in Mauretania but was reluctant to take on the cost of organizing and protecting it.

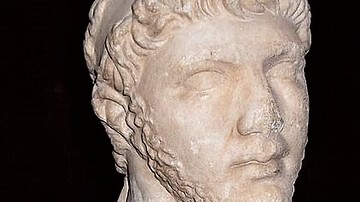

Client Kingdom

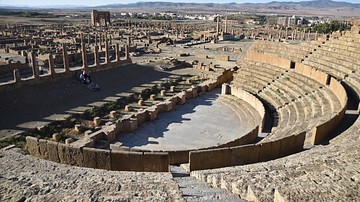

Augustus appointed the Numidian prince Juba II (r. c. 25 BCE to 23 CE) king of Mauretania as a reward for loyal service. Juba II pushed to accelerate the urbanization of Mauretania, whose inhabitants were still mostly pastoral. He expanded the cities of Volubilis and Iol, building Greco-Roman-style temples, palaces, theatres, and amphitheatres. Iol was renamed Caesarea in honour of Augustus (r. 27 BCE to 14 CE). Despite Juba II's interest in Classical architecture, the Royal Mausoleum of Mauretania built during his reign was inspired by Berber architectural traditions. The art and architecture of Mauretania was also influenced by ancient Egyptian architecture, due to Juba II's marriage to the Ptolemaic princess Cleopatra Selene II.

Juba II and his son King Ptolemy of Mauretania heavily promoted agricultural policies that favoured farming over pastoralism or nomadism. These policies were most impactful on the coast, while the interior of the country was less affected. As foreigners and vassals of the Roman Empire, Juba's dynasty faced frequent uprisings within Mauretania, especially from peoples dwelling in the mountainous interior. Other tribes, like the Baquates, were close enough to Volubilis to seriously threaten them.

At the same time, Mauretania had repeated conflicts with African tribes dwelling in and around the Sahara. Throughout the late 1st century BCE, tribes like the Gaetuli and Maurusiani raided Mauretania and other Roman territories in North Africa. Juba II and Ptolemy were unable to handle internal or external threats, and Rome was obliged to provide military assistance whenever serious threats arose. The prior settlement of Roman veterans on the coast also helped to add a base of support for Juba II.

Romanization

In 40 CE, the Roman emperor Caligula (r. 37-41 CE) had Ptolemy executed for a perceived slight and Mauretania was annexed by the Roman Empire once again. This time it was made into a Roman province, meaning that the borders of the Roman Empire now stretched across the entire coast of North Africa. In 44 CE, it was formally divided into two provinces: Mauretania Caesarensis in the east and Mauretania Tingitana in the west. Like Egypt and Numidia, these provinces were under the direct control of the emperor rather than the Roman Senate. Mauretania Caesarensis, whose capital was Caesarea, and Mauretania Tingitana, whose capital was Volubilis, were governed by equestrian procurators.

Rebellions continued to flare up in the interior of Mauretania during the first few years of Roman rule. Roman troops from Spain, Gaul, and Asia were garrisoned in the province. Mauretanian tribal armies were more mobile than the Romans and understood the terrain. They could retreat into the Atlas Mountains and Sahara, leaving the Romans to battle heat and dehydration. As a result, Roman rule was mostly restricted to the coasts. Eventually, the Romans reached a tenuous understanding with the interior tribes, who continued to be ruled by clan chieftains outside of direct Roman control. After the 1st century CE, Mauretania seems to have been largely peaceful.

This period saw the fusion of Berber and Roman culture in a process called Romanization. Over time, Libyan and Neo-Punic languages became less widely spoken as the use of Latin spread. Many Mauretanians became influential politicians, intellectuals, and military officials in the Roman Empire. Roman-style aqueducts and other infrastructure were developed throughout the country, and agricultural practices continued to shift towards Mediterranean patterns.

The country was well suited to growing olives, a staple of the Roman diet. Garum, a preserved fish paste loved by the Romans, was produced en masse in large coastal factories. Ships leaving port cities along the coast helped to feed the multitudes living in the Roman Empire. Commodities like wood, horses, and exotic animals for the arenas, were also exported from Mauretania.

To protect this trade, the Roman navy policed the sea for pirates in the ancient Mediterranean. Inland, a network of roads connected Mauretania to cities in other parts of Roman Africa. Outside of the urban centres, the pastoral tribes of Mauretania continued to make their seasonal migrations but now paid tariffs to Roman officials at certain crossings. A network of Roman forts unfolded across North Africa to regulate the passing of pastoralists and guard against hostile tribes.

Late Antiquity

In the 3rd century, Mauretanian tribes began to revolt against Roman rule again, and the Baquates became independent under their king. The arrival of previously unrecorded tribes in Mauretania and Numidia also sparked further wars in the provinces. By this period, Romans had begun to describe any Northeast African tribes living outside imperial borders as Mauri or 'Moors'.

Diocletian (r. 284-305 CE) attempted to shore up the Roman Empire's weakening frontiers by reorganizing the African provinces. The Roman Empire withdrew from most of Mauretania Tingitana including Volubilis, retaining only a small portion of the territory surrounding Tingis which was governed by the Diocese of Spain. A new province, Mauretania Sitifensis, was split from Mauretania Caesarensis. These two were ruled under the Diocese of Africa, which also included the provinces of Numidia and Africa Proconsularis. As the Roman Empire shrunk, various Moorish kings arose in Mauretania. These kings generally used Roman and Greek titles despite functioning as independent polities.

Christianity permeated Roman-controlled North Africa during the 2nd century CE, finding converts among both urban and rural populations. The decline of polytheistic worship is evidenced by the disappearance of dedications to African and Greco-Roman deities in the 3rd century. By this period, urban centres had begun a noticeable decline, characterized by failing infrastructure and declining wealth. Diocletian attempted to restore the cities and renovate dilapidated temples to Roman gods, an expensive undertaking that was not universally appreciated by the populace. In the rural farm villages of Mauretania, Christianity was the dominant religion and churches soon dotted the countryside.

Donatist Schism & Religious Violence

Schisms within the Church of Africa led to violence and unrest within Mauretania. The largest schism was caused by the Donatist sect, which broke away from the church during the 4th century CE. Many church leaders and congregations in North Africa had renounced their faith during Diocletian's persecution of Christianity, relinquishing religious objects and scriptures to the state. Others chose to martyr themselves and were imprisoned or executed. After this period of persecution ended, some who had renounced Christianity returned to their roles as clergy. One of these was Caecilian, whose election as Bishop of Africa caused great controversy. Majorinus, and his more influential successor Donatus, were named bishop by those who opposed Caecilian, creating a schism.

Donatus founded a sect opposed to the doctrine of rebaptism and the appointment of lapsed Christians in the clergy. Within a short period of time, Donatism had swept Mauretania. Most of its adherents were from the lower classes, though its clergy tended to be more literate and middle-class. Donatism was declared a heresy by the First Council of Arles in 314 CE, and the emperor Constantine I (r. 306-337) further persecuted Donatists by exiling their clergy and confiscating their churches. This did little to slow the movement's growth in Mauretania and Numidia, and by 330 CE, there were hundreds of Donatist bishops in North Africa.

A movement of religious fanatics called the Circumcellions arose in Mauretania and Numidia in connection to the Donatist controversy. Most Circumcellions came from the peasantry and opposed the social order, including the power of the land-owning class and the institution of slavery. In addition to economic grievances, the Circumcellions considered martyrdom to be the ultimate goal, with some provoking violent altercations for the purpose of dying or simply committing suicide. Over the next few decades, violence broke out between gangs and peasant armies on both sides of the controversy. The church and empire's position on Donatism was reaffirmed by emperor Constantius II (r. 337-361 CE) in 347 CE, and a Donatist rebellion was crushed.

Julian the Apostate's (r. 361-363 CE) decision to allow the return of exiled heretics reinvigorated the Donatist church. The Donatists would later help support Mauri usurpers like Firmus and Gildo who rebelled against the Roman Empire. When these rebellions failed, Donatism was greatly weakened, and the association with rebels left them permanently tarnished in the eyes of the imperial government. The Catholic bishop Saint Augustine of Hippo (354-430 CE) was vividly opposed to Donatism throughout his life and played a role in its decline by encouraging legal persecution of Donatists and attacking its theological foundation. Augustine was also present at the conference of Catholics and Donatists in 412 CE, which saw bishops on both sides debate once again. After the conference, the emperor Honorius proscribed Donatism, requiring its clergy to abandon the sect or be exiled. Although Donatism persisted until the rise of Islam in Mauretania, it would never again be the predominant sect.

Vandal & Islamic rule

As the power of the Western Roman Empire waned, its provinces were threatened by the rise of local elites who sought to carve out kingdoms of their own. Though the Berber tribes had long threatened the provincial government, the final challenge to Roman rule in Mauretania came not from the Sahara but from northern Europe. In late 406 CE, a group of Germanic tribes known to history as the Vandals crossed the Rhine and penetrated the Western Roman Empire, making their way through Gaul and into Iberia, where they had carved out a kingdom in southern Spain by the 420s CE. Control over Iberian ports gave the Vandals a measure of control over maritime trade, and they soon established a foothold in northwestern Mauretania.

The Vandals first arrived on the coast of Mauretania under King Gunderic (l. 379-428 CE), who looted its port cities. In 429 CE, King Gaiseric (r. 428-477 CE) invaded North Africa with perhaps 80,000 Vandals. They landed in Mauretania, moving east to conquer Numidia and Africa Proconsularis. These conquests disrupted Roman trade but did not immediately change the culture or society of North Africa. Unable to oust the Vandals, the Romans ultimately signed a treaty with them in 442 CE, formally recognizing the Vandal kingdom in Africa and Numidia. Meanwhile, Mauretania remained nominally under Roman control. Over the next few decades, the Vandal kingdom would gradually absorb parts of eastern Mauretania.

Gaiseric, through a combination of bribes and influence, was able to build alliances with the Moorish kingdoms in the country's interior and western fringes. These tribes aided him in his raids of Italy, including Rome. After his death, these Moors began to encroach on the Vandals' shrinking African territory. The inhabitants of these early medieval Berber kingdoms were Christian and used Latin names and titles. The Laguatan, a confederation of nomadic tribes, also moved out of Tripolitania and into Mauretania where they were generally victorious in battles against Vandal armies.

Mauretania Sitifensis was briefly reconquered in 534 CE when the Byzantine emperor Justinian I (r. 527-565 CE) sent his general Belisarius (l. 505-565 CE) to retake North Africa. Byzantine warfare against the Moors was initially successful; however, most of the former Mauretanian provinces quickly fell back under the control of Moorish kings. These kingdoms built the Jedars, monumental tombs near Tiaret, Algeria, in the 6th and 7th centuries CE. These tombs resemble pre-Roman Berber funerary architecture, emphasizing a level of cultural continuity with earlier Berber kingdoms. Small kingdoms would continue to dominate the region until the rise of Islamic Moorish empires in the High Middle Ages.