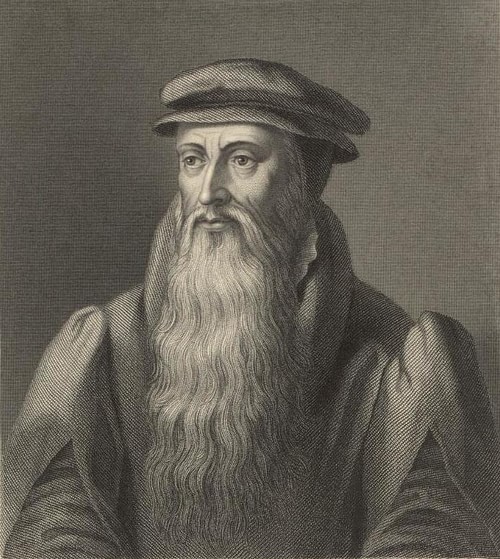

John Knox (l. c. 1514-1572) was a Scottish theologian and reformer famous for his work in advancing the Protestant Reformation in Scotland, his contentious relationship with Mary, Queen of Scots (l. 1542-1587), and establishing the Presbyterian Church of Scotland. He became the face of the Reformation in Scotland and is considered one of the most significant Protestant activists.

Knox was a priest who seems to have been converted to the Reformed vision of Christianity by the reformer George Wishart (l. c. 1513-1546), afterwards serving as his bodyguard. He traveled to England and worked with the Protestant Archbishop of Canterbury Thomas Cranmer (l. 1489-1556) then traveled to Geneva where he was significantly influenced by John Calvin (l. 1509-1564) and his model of Christianity as well as by Heinrich Bullinger (l. 1504-1575). He was well-known for his fiery sermons and refusal to compromise on religious issues as well as for his stand against women in positions of authority. Knox's The First Blast of the Trumpet Against the Monstrous Regiment of Women (1558), published anonymously, was considered misogynistic even in his time, and today it is frequently cited as epitomizing anti-feminist writings.

His relationship with Mary, Queen of Scots was informed not only by his views of women in positions of authority but by her religion in that she was a Catholic monarch ruling an increasingly Protestant country. The two met on several occasions, during which Mary tried to find a compromise to their differences, which Knox rejected. When Mary was arrested, Knox called for her execution and supported her son James VI of Scotland (l. 1566-1625) as successor.

Knox continued to involve himself in politics, trying to bring the Scottish monarchy in line with his vision of Christianity, until dying of natural causes in Edinburgh on 24 November 1572. Prior to the Reformation in Scotland, the Scottish government relied on France as an ally against the English, but after Knox successfully established the Protestant Church of Scotland, Catholic France (as well as Spain) was seen as a threat and Protestant England as a friend. James VI would become James I of England in 1603, uniting Protestant Scotland and England, and Knox is recognized as one of the more significant players, if not the most important, in providing the foundation for the Acts of Union of England and Scotland in 1707, the beginning of the United Kingdom, as well as influencing later events including the organization of the United States government.

Early Life & Conversion

Little is known of Knox's early life, and even the year of his birth is contested as he may have been born as early as 1505. He was the son of a merchant in the town of Haddington in East Lothian, Scotland, and his mother died when he was young. His older brother, William, who followed his father's trade, may have helped raise him and sent him to school instead of having him as an apprentice. Knox excelled in his studies and went on to the University of St. Andrews. He was ordained as a priest in Edinburgh in 1536.

At this time, Scotland was still a Catholic country aligned with France against their longtime adversary, England. When England rejected Catholicism in 1534 under King Henry VIII of England (r. 1509-1547), Protestant missionaries began smuggling anti-Catholic pamphlets and tracts from England into Scotland, though even before this, the ideas of the Reformation of Martin Luther (l. 1483-1546) in Germany and Huldrych Zwingli (l. 1484-1531) in Switzerland were already exerting influence there. The best-known early Scottish Reformer was Patrick Hamilton (l. 1504-1528), who had studied in Paris and Germany before returning to Scotland to preach Lutheran doctrine. He was burned at the stake as a heretic in 1528 at St. Andrews. Hamilton's execution only attracted more people to the Protestant vision, and this was encouraged by George Wishart, who had studied in Zürich and began openly preaching the Reformed concepts of Zwingli and Heinrich Bullinger.

Knox, at this time, was a notary priest in East Lothian, serving as a tutor to the children of two Scottish lords, and seems to have been converted by Wishart sometime around 1543. Knox left his position to become Wishart's bodyguard, regularly appearing with a two-handed sword near Wishart during sermons. James V of Scotland (r. 1513-1542) had avoided widespread persecution of Protestants, but after his death in 1542, this policy changed under James Hamilton (l. c. 1519-1575), regent for James V's heir – the infant Mary, Queen of Scots – Mary of Guise (l. 1515-1560, Mary's mother), and Cardinal David Beaton (l. c. 1494-1546), who began a systematic purge of Protestant activists. Wishart was arrested in 1545 and burned at the stake in March 1546.

Galley Slave & England

Wishart had sent Knox away prior to the arrest, suggesting he return to the safety of the two lords, Hugh Douglas of Longniddry and John Cockburn of Ormiston. Both of these men were sympathetic to the Reformation, however, and had to remain on the move, with their families and Knox, to avoid arrest and execution. In May 1546, Cardinal Beaton was assassinated at St. Andrews Castle by Wishart's supporters, who then took it over and established a safe haven for Protestants. Knox arrived with his two pupils almost a year later in April of 1547 and quickly became chaplain.

Mary of Guise, who could not allow a hostile armed garrison, had a French fleet attack the castle in June of 1547, taking it less than a month later and imprisoning those who surrendered. Some were incarcerated in France or elsewhere and a number taken as galley slaves rowing French ships. Knox remained a slave for 19 months, rowing daily and surviving on meager rations, until he was released in 1549, but there is no account relating how this happened. All that is known is that by April 1549, Knox was in England as a licensed minister of the Church of England, posted to Berwick-upon-Tweed. While there, he met his wife, Margery Bowes (d. c. 1560), but there is no record of when they were married.

In England, Knox became a popular preacher, was associated with Thomas Cranmer, revised the Anglican Book of Common Prayer, and became a royal chaplain to King Edward VI of England (r. 1547-1553). How a Scottish galley slave was elevated so quickly between 1549-1551 is unclear, but he was in high demand as a preacher, delivering sermons to the king and his court, until Edward VI's death in 1553 when the Catholic Mary I of England (r. 1553-1558) came to power. Best known as 'Bloody Mary' for her systematic persecution of Protestants, Mary's efforts to stamp out the Reformation in England forced Knox to send his wife to her family in Scotland and flee to the safety of Protestant Geneva.

Geneva & Scotland

In Geneva, he became a close associate of John Calvin and adopted much of his theology as well as that of Heinrich Bullinger, who had influenced Calvin. Among the precepts Knox adopted were the concepts of covenant theology – that God and humanity have an agreement regarding eternal salvation – and predestination – that God has already chosen those who will be saved, and one's works in life cannot change God's decision. Knox was particularly impressed by how Calvin had instituted Reformed policies in Geneva and thought this model would work as well in Scotland.

On Calvin's advice, Knox accepted a call to minister to an English congregation in Frankfurt, Germany, and remained there until 1555, when a pamphlet he had written against Mary Tudor came to light and he was asked to leave. He returned to Scotland and was surprised to find how the Reformation had taken hold. He resumed old friendships and acquaintances from the early days of the Reformation, some of whom were now powerful lords, and he became a celebrity preacher.

Emboldened by how well his sermons were received, he wrote to Mary of Guise in 1556, admonishing her for holding onto a false faith and encouraging her to embrace the tenets of the Reformation. The letter was never answered, and there was no response otherwise, but the clerical authorities in Scotland thought the action serious enough to warrant an examination, and he was called to Edinburgh before a tribunal. He arrived with so many powerful supporters, the clerics canceled the event. Soon afterwards, Knox left for Geneva with his wife and her mother, answering a call from his old congregation there. After he left, the clerics burned him in effigy.

Geneva & The First Blast

He preached three sermons a week in Geneva, ministered to members of his congregation, and corresponded with other reformers as well as writing his famous (or infamous) work The First Blast of the Trumpet Against the Monstrous Regiment of Women, denouncing Mary Tudor, Mary of Guise, and Mary, Queen of Scots as unnatural abominations in the eyes of God, arguing that the Bible prohibited women to rule over men.

Even given the misogyny of the time, Knox's work was considered extreme and, it seems, even by him as he published it anonymously. He had previously spoken with both Calvin and Bullinger on women in positions of authority, and both had told him, more or less, that God could work His will through any vessel and had His own reasons for allowing women like Mary Tudor to reign. Knox, clearly, felt differently as would become clear afterwards in his relationship with Mary, Queen of Scots, who had either read the work or understood his feelings on women in power from his sermons. Somehow, his name became attached to the work as he was associated with it less than a year after its 1558 publication. Scholars Richard G. Kyle and Dale W. Johnson comment:

The First Blast gained for Knox a reputation among his contemporaries of being a revolutionary, and among later generations of being a woman hater. Knox's misogynist image, however, is not accurate because – outside of The First Blast – his writings contained few denunciations of the female sex. On the contrary, out of Knox's surviving letters, more than half were written to women and many of them showed a high regard for the female sex. (97)

While that may be, The First Blast remains the best-known work by Knox along with his The History of the Reformation in Scotland (1559-1566) and continues to define his official stand on female rulers and women in positions of authority over men. Although, as Kyle and Johnson point out, his arguments were not original and his views were held by many people, men and women, Knox's articulation of the claims was more powerful than others, and, recognizing this, Mary Tudor had the work officially condemned and banned in England as seditious.

When Mary Tudor died, Elizabeth I of England (r. 1558-1603) came to the throne, and all the Protestant refugees in Geneva who had fled England could now return home safely under a Protestant queen. Knox prepared to return to Scotland but was delayed when Elizabeth I, who also rejected The First Blast, refused him passage through her realm.

Reformation & Mary

Knox had not even been in Scotland a week before his anti-Catholic sermons sent Protestant mobs on a rampage, destroying the friaries of Blackfriars and Greyfriars in Perth, and looting both. Mary of Guise mobilized an army to put down the revolt, but her declaration of martial law to enforce Catholicism and use of French soldiers and mercenaries paid by the French disgusted some of the Scottish lords, who deserted her for Knox. While this was going on, Knox had returned to St. Andrews Castle where he continued to preach the same kinds of sermons and encouraged the same vandalism and destruction as before.

Knox became the political and spiritual force behind the Reformed efforts to oust Mary of Guise, enlisting the aid of Elizabeth I, who set aside her personal distaste for Knox to break France's hold in Scotland. English troops arrived in 1559, but Mary of Guise died in June 1560, and hostilities ended with the Treaty of Edinburgh and the withdrawal of the French. Knox wasted no time in convening an assembly, at which he contributed to the Scots Confession (drawing on Bullinger's Helvetic Confessions), which would become the Confession of Faith for the Presbyterian Church and, later, the Book of Discipline outlining the democratic order of the new church.

Knox rejected the Anglican organizational hierarchy of archbishops, bishops, and priests and organized his church as a presbytery, a body of elders who made decisions implemented with the agreement of deacons and ministers. The Presbyterian Church of Scotland was a democratic organization with no central figure in authority and full voting rights for all elders in good standing. While Knox was organizing the church, his wife Margery died, leaving him to care for their two sons, Nathaniel and Eleazar, whose lives at this time are obscured in history by Knox's ongoing contention with Mary, Queen of Scots.

Mary arrived in Scotland in 1561 and announced that, though a Catholic monarch, she would not impose her religion on her subjects. She requested compliance from Protestant ministers in maintaining religious tolerance, which most agreed to. Knox, however, now preaching at the former St. Giles Cathedral, renamed the High Kirk of Edinburgh, refused to compromise, noting that there was only one true faith and believers should not tolerate the false beliefs of Catholics. Mary summoned Knox to appear before her several times in an attempt to enlist his help in governing Scotland peacefully, but, each time, Knox made it clear that he would continue to preach the truth as he understood it and no monarch had the authority to dictate the interpretation of the Bible or the content of sermons based on it.

Throughout her reign, Knox refused any compromise or concession, which, to many later scholars and writers, has been seen as an honorable characteristic of a devoted Christian pastor. Had he been able to recognize the value of religious tolerance, however, he could have prevented the violence and destruction, especially in Fife, Perth, Dundee, Edinburgh, and St. Andrews, that came to be associated with the Reformation in Scotland. When Mary was arrested and imprisoned in Loch Leven Castle, Knox called for her execution and supported her son, James VI as her successor.

James VI was firmly Protestant and succeeded Elizabeth I as monarch of England in 1603 becoming King James VI of Scotland and James I of England, among whose cultural contributions was the King James Bible in 1611. England and Scotland were only cooperating at this time because of their common religious beliefs, and in Scotland, these had been firmly established by Knox. Prior to his return from Geneva in 1559, Catholicism was still widely practiced, whereas, after he had established the Kirk of Scotland, it was relegated to the Highlands and the islands.

The ruins of many Catholic monasteries, convents, and churches throughout Scotland, even in the Highlands, can be visited in the present day, the destruction of a number of them traced back to Knox's time in the pulpit. The violence he encouraged by his sermons, however, is often overlooked by scholars who regard him as a principal player in laying the foundation for the United Kingdom by establishing Scotland as a Protestant country.

Conclusion

Knox married the 17-year-old Margaret Stewart in 1564, creating the same kind of public outcry as when reformer William Farel (l. 1489-1565) of France had married his teenage bride. Knox and his second wife would have three daughters, and he is said to have lived his final years in the building now known as the John Knox House on High Street in Edinburgh (though this claim is challenged). He died of natural causes and was buried in the St. Giles cemetery. Later, the bodies buried there were removed to the Greyfriars cemetery but not Knox's because people feared his wrath from beyond the grave at being disturbed. The site of the St. Giles cemetery is now a parking lot, and Knox's grave is thought to be under space 23.

Knox was a controversial figure in life and has only become more so in the centuries since his death. Kyle and Johnson comment:

Revolutionary or Servant of God? Thundering prophet or consummate politician? Nasty old man or spiritual pastor? Ardently loved or passionately despised? Will the real John Knox please stand up? John Knox indeed was a complex and contradictory figure. To be sure, he displayed several faces and wore many hats. (1)

The contradictory nature of Knox continues to affect the interpretation of his legacy as some credit him with establishing the democratic principles in his church, which would later influence the Founding Fathers of the United States, and others note how his reforms resulted in the dramatic loss of rights for women in Scotland, especially in education. He is recognized today as one of the most powerful and persuasive activists of the Protestant Reformation, but how his legacy should be understood, and even what that is, continues to be debated.