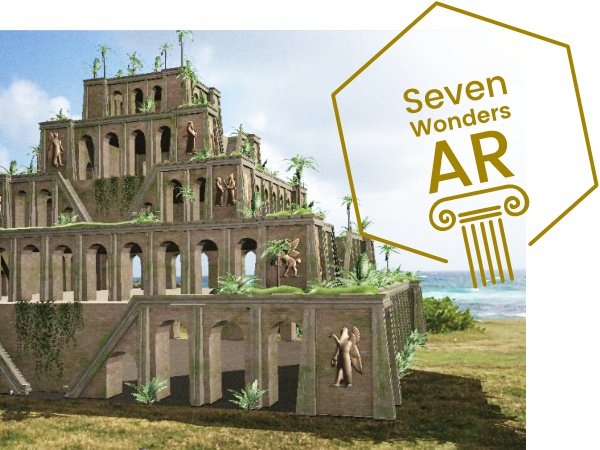

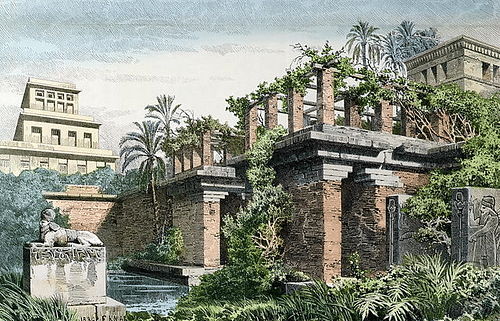

The Hanging Gardens of Babylon were the fabled gardens which beautified the capital of the Neo-Babylonian Empire, built by its greatest king Nebuchadnezzar II (r. 605-562 BCE). One of the Seven Wonders of the Ancient World, they are the only wonder whose existence is disputed amongst historians.

Some scholars claim the gardens were not in Babylon but actually at Nineveh, capital of the Assyrian Empire, while others stick with the ancient writers and await archaeology to provide positive proof. Still others believe the gardens are merely a figment of the ancient imagination. Archaeology at Babylon itself and ancient Babylonian texts are silent on the matter, but ancient writers describe the gardens as if they were at Nebuchadnezzar's capital and still in existence in Hellenistic times. The exotic nature of the gardens compared to the more familiar Greek items on the list and the mystery surrounding their location and disappearance have made the Hanging Gardens of Babylon the most captivating of all the Seven Wonders.

Babylon & Nebuchadnezzar II

Babylon, located about 80 km (50 miles) south of modern Baghdad in Iraq, was an ancient city with a history of settlement dating back to the 3rd millennium BCE. The greatest period in the city's history was in the 6th century BCE during the reign of Nebuchadnezzar II when the city was the capital of the Neo-Babylonian Empire. The empire had been founded by Nebuchadnezzar's father Nabopolassar (r. 625-605 BCE) after his victories over the Assyrian Empire. Nebuchadnezzar II would go on to even greater things, including the capture of Jerusalem in 597 BCE. The Babylonian king then set about making his capital one of the most splendid cities in the world. The Ishtar Gate was built c. 575 BCE with its fine towers and depictions in tiles of animals both real and imaginary, a 7-20 km brick double wall surrounded the city - the largest ever built - and then, possibly, he added the extensive pleasure gardens whose fame spread throughout the ancient world.

Naming & Descriptions

The majority of scholars agree that the idea of cultivating gardens purely for pleasure, as opposed to the production of food, originated in the Fertile Crescent, where they were known as a paradise. From there the notion would spread throughout the ancient Mediterranean so that by Hellenistic times even private individuals, or at least the wealthier ones, were cultivating their own private gardens in their homes. Gardens were not just about flowers and plants, either, as architectural, sculptural, and water features were added, and even the views were a consideration for the ancient landscape gardener. Gardens became such a desired feature that fresco painters, such as those at Pompeii, covered entire walls of villas with scenes which gave the illusion that on entering a room one was also entering a garden. All of these outdoor pleasant places, then, owed their existence to ancient Mesopotamia and, above all, to the magnificent Hanging Gardens of Babylon.

The Hanging Gardens of Babylon were sometimes referred to as the Hanging Gardens of Semiramis after the semi-legendary and semi-divine female Assyrian ruler thought by the Greeks to have extensively rebuilt Babylon in the 9th century BCE. Herodotus, the 5th-century BCE Greek historian, describes the impressive irrigation system of Babylon and the walls but does not mention any gardens specifically (although the Great Sphinx is also curiously missing from his description of Giza). The first mention in an ancient source of the gardens is by Berossus of Kos, actually, a priest named Bel-Usru from Babylon who relocated to the Greek island. Writing c. 290 BCE, Berossus' work survives only as quoted excerpts in that of later writers, but many of his descriptions of Babylon have been corroborated by archaeology.

Several other sources describe the gardens as if they were still in existence in the 4th century BCE, but all were written centuries after the reign of Nebuchadnezzar and all were written by writers who almost certainly never visited Babylon and who knew little of either horticulture or engineering. Strabo, the Greek geographer (c. 64 BCE - c. 24 CE), describes the location of the gardens as by the Euphrates, which ran through ancient Babylon, and a complicated machinery of screws which drew water up from the river to water the gardens. He also mentions the presence of stairs to reach the various levels. Meanwhile, the Greek historian Diodorus Siculus, also writing in the 1st century BCE, notes that the terraces sloped upwards like an ancient theatre and reached a total height of 20 metres (65 ft). He describes the terraces as being built on pillars and lined with reeds and bricks.

Mesopotamian Gardens

There are known precedents for large gardens in Mesopotamia which pre-date those said to have been at Babylon. There are even depictions of them, for example, on a relief panel from the North Palace of Ashurbanipal (668–631 BCE) at Nineveh, now in the British Museum, London. Indeed, some scholars suggest that the whole Babylonian gardens idea is the result of a monumental mix-up, and it is Nineveh which actually had the fabled wonder, built there by Sennacherib (r. 705-681 BCE). There is ample textual and archaeological evidence of gardens at Nineveh, and the city was sometimes even referred to as 'old Babylon'. In any case, even if the hypothesis of Nineveh is accepted, it still does not preclude the possibility of gardens at Babylon.

There were also gardens after the supposed date for the Hanging Gardens of Babylon, those at Pasargadae in the Zagros Mountains built by Cyrus the Great (d. 530 BCE), for example. All such gardens usually had terraces to aid irrigation, high walls to provide shade, trees were clustered together so as to better maintain their vital moisture and withstand scorching winds, and, of course, all were located near an abundant water source. That gardens were commonly associated with palaces (in just about every culture from ancient China to Mesoamerica) has led some scholars to speculate that the gardens at Babylon, if they did exist, would also have been near or in one of the royal palaces of Nebuchadnezzar on the banks of the River Euphrates.

The Seven Wonders

Some of the monuments of the ancient world so impressed visitors from far and wide with their beauty, artistic and architectural ambition, and sheer scale that their reputation grew as must-see (themata) sights for the ancient traveller and pilgrim. Seven such monuments became the original 'bucket list' when ancient writers such as Herodotus, Callimachus of Cyrene, Antipater of Sidon, and Philo of Byzantium compiled shortlists of the most wonderful sights of the ancient world. In many early lists of the ancient wonders the gardens were listed alongside the magnificent walls of the city of Babylon which were, according to Strabo, 7 km long, in places 10 metres thick and 20 metres high, and regularly punctuated by even taller towers. The author P. Jordan suggests that the gardens made it on to the established list of Seven Wonders of the Ancient World because they "appealed for sheer luxurious and romantic perversity of endeavour" (18).

After Nebuchadnezzar, Babylon continued to be an important city as part of the Achaemenid (550-330 BCE) and Seleucid Empires (312-63 BCE), the rulers of both entities often using the palaces at Babylon as their residence. Taken over in succession by the Parthians, the Arsacids and Sasanids, the city still maintained its regional strategic significance and, therefore, it is perfectly possible that the gardens survived for several centuries after their construction.

Systematic archaeological excavations began at ancient Babylon in 1899 CE, and although many ancient structures such as the double walls and the Ishtar Gate have been found, there is no trace of the legendary gardens. A promising find of 14 vaulted rooms during excavations of the South Palace of Babylon turned out - after tablets were subsequently discovered on the spot and deciphered - to be nothing more spectacular than storerooms, albeit large ones. Another series of excavations much nearer the river and part of another of the king's palaces have revealed large drains, walls, and what could have been a reservoir, all necessary irrigation features for the gardens but not proof positive of the fabled lost wonder.

Aside from the silence of archaeology, significantly, no Babylonian sources mention the gardens - either their construction or existence, even in a ruined state. This is perhaps the most damning evidence against the gardens having been at Babylon because the surviving Babylonian records include comprehensive descriptions of Nebuchadnezzar's achievements and construction projects right down to the street names of Babylon.