Flann Sinna (r. 879-916 CE) was a High King of Ireland from the Kingdom of Mide (Meath) and a member of the Clann Cholmain, a branch of the Southern Ui Neill dynasty. His name is pronounced “Flahn Shinna” and means “Flann of the Shannon”. He is best known as an effective high king of Ireland who consolidated the power of the Kingdom of Meath while honoring his obligations to other kingdoms, famous for his victory at the Battle of Ballaghmoon in 908 CE, and erecting monuments to commemorate his achievements; most notably the Cross of the Scriptures at the Abbey of Clonmacnoise.

He was an important patron of this religious community and is also responsible for the cathedral (also known as Temple McDermot) and possibly the South Cross still extant at the site. This patronage seems at odds with accounts from the Annals of the Kingdom of Ireland (also known as The Annals of the Four Masters, c. 1616 CE) which report that Flann Sinna was responsible for the sack of a number of churches and monasteries throughout Ireland, and this has led to criticism of his reign by later writers.

His patronage of Clonmacnoise is no doubt due to his mother who retired to and was later buried there. Although the ancient sources provide a more or less favorable account of his reign, Flann Sinna clearly faced opposition and twice had to put down a rebellion by one of his sons, revolts by other kingdoms, and faced various other oppositions to his reign.

The Ui Neill & the Kingdoms of Ireland

Flann Sinna ruled as a king of the Connachta Dynasty which claimed descent from the legendary Celtic hero Conn of the Hundred Battles. The Connachta Dynasty is synonymous with the Ui Neill Dynasty; the latter designation only becoming prominent in later usage once the Ui Neill had established themselves. The Connachta genealogy traces its ancestry from Conn to the historical or semi-historical king Niall Noigiallach (Niall of the Nine Hostages) from whom all the other Ui Neill kings descend.

According to legend, Niall and his brothers were out hunting one day when they encountered an old woman by a well. She refused to give them any water unless they each kissed her. Three of the brothers refused and one only gave her a quick peck on the cheek, but Niall kissed her fully on the lips and found her transformed into a beautiful goddess. She rewarded him by granting him kingship of Ireland which would be passed on to his descendants for generations.

While there is no doubt the Ui Neill who descended from Niall were a powerful dynasty, it is inaccurate to say that they ruled Ireland as traditional kings over the next few centuries. The Ui Neill divided the land between them as the Northern Ui Neill and the Southern Ui Neill, each branch taking turns sending a king to rule from Tara, but there were many smaller kingdoms throughout Ireland at this time which were autonomous or semi-autonomous states.

When a king came to power, he would demand hostages from other kingdoms – those in Ireland and abroad - to encourage compliance. A king who was able to command a large number of these hostages was considered far more powerful than one who was only able to have a few sent to him. Niall's name indicates he was among the most powerful because he held one hostage each from the five provinces of Ireland (Connacht, Leinster, Meath, Munster, and Ulster) and one each from the Britons, the Franks, the Saxons, and the Scots.

Whether Niall ever held such hostages – or if he even existed – is doubtful but the story, as related by later Ui Neill authors, is intended to make clear the dynasty's great legacy and power: just as Niall Noigiallach could command the compliance of so many others, so could his descendants.

The High King of Ireland

The term 'hostages' should not be understood in the modern sense. A hostage in ancient times was an important member of a ruler's family or court who was sent to another monarch as a gesture in ratifying a treaty. A hostage would be well cared for, educated in the culture he or she was sent to, and would eventually be returned safely; unless that hostage's monarch broke the terms of peace or failed to comply with an agreement. Hostages were sent from the smaller kingdoms to those more powerful not only to conclude a peace but also when a new king came to the throne.

The concept of a 'king' should also be understood somewhat differently than in the modern sense. There were many 'kings' throughout Ireland in the 9th century CE but most of them reigned over small areas and had limited power. There were no large cities, towns, or villages in early Ireland, and smaller rural communities were known as raths (wooden huts clustered around a central meeting house and surrounded by earthen walls) while larger fortified communities were called cashels (stone forts). The raths would submit to the lord of whatever kingdom they were in, who ruled from a cashel, and these kings would protect them, lead them in time of war, and participate in public religious rituals.

Scholars Peter and Fiona Somerset Fry elaborate:

Ireland was divided into numerous very small kingdoms which loosely belonged to one or other of the five larger provincial kingdoms of Connact, Leinster, Meath, Munster, and Ulster. Probably there were more than 100 smaller kingdoms in the earlier period and as many as 150 or so by the seventh century. They were known as Tuatha (Tuatha = tribe, or people, or clan) and each was ruled by a ri, or king, who might, if his tuath was very small, be an under-king to a greater ri…This vassalage would generally be marked by the giving of a hostage, or hostages, to the higher king and was often quite voluntary, for it afforded protection for the smaller tuath. (29-30)

The concept of a king evolved from tribal chiefs to lords of a region and then to a single overlord of those lesser kings and princes. This overlord, who is said to have presided over all of Ireland, was the High King. This king was the embodiment of the people, and his coronation is thought to have included a ritual mating with the goddess of the land to ensure fertility and prosperity.

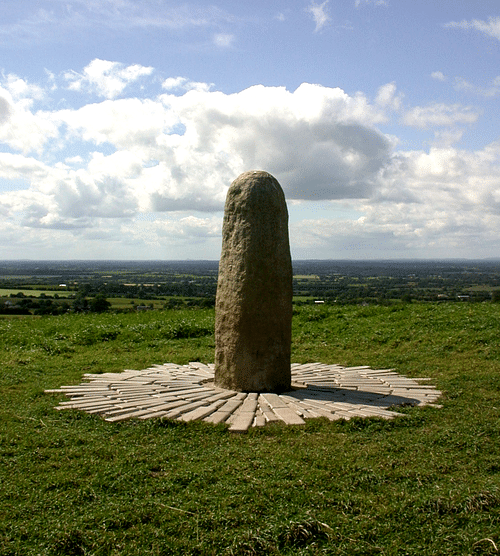

The king of any region in Ireland was supposed to care for his people; the high king was supposed to care for all the people and command their unconditional allegiance. While this may have been true in theory or policy, it was not so in practice; the High King of Ireland only had control over his own territory and had to make the same kinds of treaties with other kingdoms as the lesser kings did with each other. The difference, it seems, is that the high king commanded greater respect owing to his coronation at the Hill of Tara.

The Hill of Tara

Tara was the sacred site associated with the legend of the brothers Eber and Eremon of the Milesians who had divided the rule of Ireland between them peacefully in antiquity; Eber taking the south and Eremon the north. Peace prevailed until Eber's wife wanted the most beautiful three hills in Ireland for herself – and chief among these was the Hill of Tara which belonged to Eremon. Eremon's wife Tea became enraged at the request and the two brothers went to war. Eber was killed and Eremon was crowned king of all Ireland at Tara, thus initiating the tradition of the high king's coronation at that site.

Tara would be developed as a place of assembly for the enacting and reading of laws and for religious festivals under the reign of Cormac MacArt (c. 3rd century CE), considered the greatest of the Irish kings and author of the Brehon Law, but it is clear the site was an important religious and political center long before. The oldest monument at Tara is the Mound of the Hostages, a Neolithic passage tomb, dating from c. 3000 BCE and so named because it was where hostages would be exchanged between kings.

Flann Sinna's Rise to Power

Flann Sinna was born c. 848 CE, the son of one of these kings, Mael Sechnaill mac Maele Ruanaid (r. c. 846-862 CE) of the Southern Ui Neill and the queen Land ingen Dungaile (d. 890 CE) of the Kingdom of Osraige. Mael Sechnaill (also known as Mael Sechnaill I) assassinated anyone who would have stood in his path to power and was crowned King of Tara in 846 CE.

He spent the greater part of his reign battling Viking raiders, while also allying himself to Norse chieftains in warring on other Irish kingdoms, and then using diplomacy and threats of further violence to consolidate his power. Mael Sechnaill's initiatives were so successful that, when he died, he was hailed as High King of All Ireland.

He was succeeded by Aed Findliath (r. 862-879 CE) who married Land ingen Dungaile in keeping with the tradition of a successor marrying the king's widow. Land ingen Dungaile chose to devote herself to a life of piety shortly afterwards and went to live at Clonmacnoise. Aed Findliath then married Mael Muire ingen Cinaeda (d. 913 CE), daughter of Kenneth MacAlpin, King of the Scots. Aed Findliath had opposed Mael Sechnaill and met him in battle while allied to the Norse kings of Dublin. It is possible that Flann took part in these wars but there is no proof, and nothing is known of Flann's youth until he takes the first steps to secure the kingship for himself.

Flann married the princess Gormlaith ingen Flann mac Conaing, daughter of the king of Brega, c. 870 CE. The Kingdom of Brega was important as it held the Hill of Tara, and Gormlaith's father, Flann mac Conaing, was a powerful king. Having established himself in the royal house of Brega, Flann might have been content but his ambition was to reign as high king just as his father had.

As noted, the tradition at this time was for the Ui Neill to alternate the honor of high king between the northern and southern branches. After Aed Findliath of the north, a king would then be chosen from the south. The likely choice would have been Flann Sinna's second cousin Donnchad son of Aedacan, king of Mide, but Flann had other plans. He divorced Gormlaith and married the princess Eithne (d. 917 CE), the daughter of Aed Findliath, thus establishing himself in the house of the high king, and then assassinated Donnchad. When Aed Findliath died in 879 CE, Flann was chosen as High King of Ireland and crowned at Tara.

Flann Sinna's Reign

Flann's first step as high king was to divorce Eithne and marry his step-mother Mael Muire; his second was to demand hostages from the other kingdoms. When the demand was refused by some of these, he followed his father's example and allied himself with Norse-Gaels and other Norse chiefs and attacked the region of Armagh in a show of strength; the other kingdoms then complied and sent hostages to Tara.

Throughout the next 20 years of his reign, Flann would repeat this tactic a number of times as he supported one kingdom's claims against another with the help of Norse allies from Dublin. He also fought the Norse in Ireland, however, and was defeated by them under the leadership of Sichfrith son of Imair (brother and successor of Bardr mac Imair), King of Dublin (c. 883-888 CE), at the Battle of the Pilgrim c. 887 CE.

Although defeated, Flann's power as king is evident at this time as he was able to raise an army from a number of different kingdoms. Scholar N. J. Higham notes how “the fact that Aed son of Conchobar, king of Connact and Lergus son of Cruinnen, Bishop of Kildare were numbered amongst the Irish dead at this battle indicates that [Flann's] over lordship was recognized far beyond the borders of Mide alone” (93). Flann was clearly ruling as high king of a united country but could not control his own house.

In 901 CE his son Donnchad Donn (from his marriage to Gormlaith) rebelled. Flann blamed this on his son's associates and tracked them to the abbey at Kells, where he slaughtered them. Donnchad was spared and seems to have returned to the role of a dutiful son. Flann's reign continued unchallenged, but it is interesting to note that the annual festival known as the Fair of Tailtiu, honoring the fertility goddess Tailtiu, was held only twice during his reign.

The significance of this is that the fair (also known as the Tailteann Games) was a celebration of unity, and the fact that it was not celebrated suggests strong objections to Flann's policies as high king which may have marginalized some kingdoms. Even when Flann seems to have done his best to keep the kingdoms at peace and in some degree of equality, however, they still found reason to fight amongst themselves.

The Battle of Ballaghmoon

In 908 CE, the king of Munster, Cormac mac Cuilennain (r. 902-908 CE) was encouraged to make war on the Kingdom of Leinster by his advisor Flaithbertach mac Inmainen (d. 944 CE). Flaithbertach claimed that Leinster owed Munster money for chief-rent as they occupied some of Munster's land. Leinster's king, Cerball mac Muirecain, was Flann Sinna's son-in-law and, after refusing any payment to Munster, he called on Flann for aid in defense.

Cormac mac Cuilennain was a highly respected king who was renowned as a scholar and man of piety. Flann had no desire to go to war against him, and Cormac himself did not want a war at all. It had been foretold by omens that, if he launched the attack against Leinster, he would die in battle, but that aside, it was simply not in his nature to be the aggressor. The instigator was Flaithbertach who seems to have sincerely believed that Cormac's honor as king was being slighted by Leinster.

The omens were bad for Munster from the beginning as Flaithbertach was thrown from his horse as the troops assembled. This was taken as a sign by a number of the men who refused to follow their king into battle. Once the two armies engaged, Cormac was thrown from his horse, breaking his neck, and died on the field.

A Leinster soldier found his body and cut off his head, presenting it later to Flann. Scholar Martin Haverty, citing the Annals of Ireland, writes that, far from being pleased, Flann “only bewailed the death of so good and learned a man and blamed the indignity with which his remains had been treated” (122). Over 6,000 men from Munster were killed at Ballaghmoon, but this did not deter other kingdoms from asserting claims which also had to be proven in battle.

Rebellion & Decline

The Kingdom of Breifne rebelled in 910 CE and was defeated. Flann's old home of the Kingdom of Brega revolted in 913 CE, and he responded by razing a number of communities. It is from this period that he gets his reputation as a destroyer of churches. It is unclear whether these churches and abbeys were destroyed as part of a wider campaign or were chosen for particular resonance in the community or were instigators in the revolt.

In 915 CE Donnchad Donn rebelled again, this time in concert with his brother Conchobar. They were defeated, not by Flann, but by his vassal Niall Glundub (r. 916-919 CE), son of Mael Muire and Aed Findlaith of the northern Ui Neill. Flann had defeated Niall in battle at Crossakiel years before and the two had formed an alliance through the marriage of Flann's daughter Gormlaith ingen Flann Sinna to Niall.

In 914 CE, Niall had killed Flann's son Oengus in a battle which may have been a part of the other brothers' rebellion of 915 CE. Flann was certainly an older man at this time but still seems to have been able to effectively put down the rebellions of Breifne and Brega. It is likely he was unable to cope with the rebellion of his own sons and left it to Niall Glundub.

Flann Sinna died of natural causes in May of 916 CE and was succeeded by Niall Glundub as high king. Niall would continue Flann's policies but not nearly as successfully. He marched his armies against the Norse of Dublin in 919 CE and was killed in battle. He was succeeded by Donnchad Donn who was nowhere near the king his father had been. For all his faults, Flann Sinna is remembered as an effective ruler who tried to do his best for his people, and when he died, he was mourned as the High King of a united Ireland.