Chitrali Mythology developed in the region of Chitral, the tallest portions of the Hindu Kush mountains, where the Chitrali people, at the juncture of South, Central, West, and East Asia, were exposed to many external cultural influences. This mythology developed throughout many millennia during which changes in the region led to the adoption of new sets of cultural beliefs in Chitral. Though not much is known as to what the ancient belief system of the Chitralis was, traditions have preserved the tales of many creatures and entities of the archaic mythology which show a strong synthesis of external influences with the local cultures. The main creatures include fairies and phoenixes, cyclopes and fire giants, ghoul horses and celestial wolves, pixies and giants amongst others. Each creature is unique in its links to creatures of other ancient neighboring mythologies.

Creatures of Chitrali Mythology

Peris (Fairies)

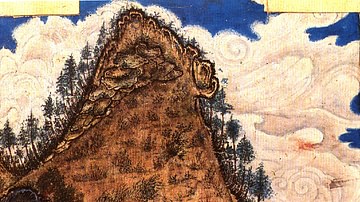

Fairies enjoy the most reverence in Chitrali mythology, and nature is taken as their domain. Most Chitralis consider the 25,000 ft (7,600 m) high Terich Mir (King Of Darkness), the highest mountain of the Hindu Kush Range, to be the famed Koh e Kaaf of eastern mythologies and refer to it as Peristan (Land of the Fairies). This mountain is believed to be the ultimate stronghold of the fairy folk where the fairies reside in a colossal golden palace alongside surrounding smaller mountain peaks which also house fairy folk and their forts.

The most important role that fairies play is as shepherds to the dominant fauna in the region. It was believed that each wild markhor herd is guarded by a fairy and so every hunter had to first make an offering to the guardian shepherd of the herd which would either give its permission or stop the hunter and would even punish hunters if they were to oppose its will.

According to legend, fairies and the Chitralis could intermarry. The most famous story features the fairy princess born to the Mehtar (ruler) of Chitral who was often reported to be seen moving atop her horse in Chitral, even though the supposed father of the oft-seen fairy died 400 years ago. It was believed that whenever calamity struck, many entities belonging to the fairy realm came to the aid of the Chitrali warriors. Every fort had fairy drums which would be beaten at times of war as both humans and the fairies would march on the war tune known as zangwar into battle together.

Khangi (Domestic Fairy)

Khangis are domestic fairies, only found in spacious areas such as forts and large houses where they are considered intrinsically a part of the family and are often spotted moving about the house. They are both protective and take part in household chores, such as picking fruit, and families would prepare separate food for the khangi. If no offering was made, a khangi would create a commotion until fed. Similar domestic fairies can be found in all North European mythologies, such as Puck in English mythology or Hinzelmann in German mythology.

Jashtan (Pixie)

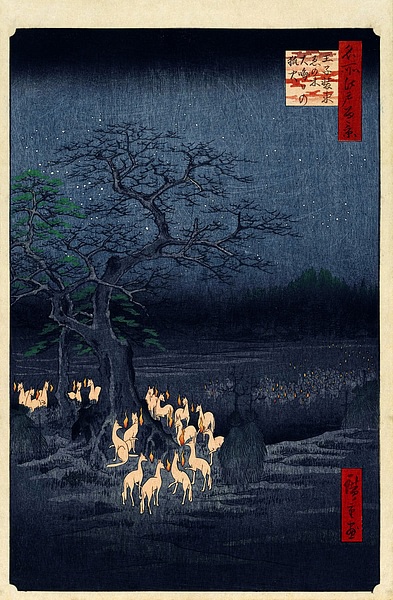

Jashtans are special pixies known for their autumn festivals. They occupy the Chitrali houses in summer when people are doing agricultural chores outside and so when autumn arrives a special festival known as the Jashtan Dekeik (Assembly of the Jashtans) takes place where every nook and cranny of the house is cleaned with a thorny stick. It is then announced to the jashtans that they should now migrate to the south where the weather is warmer. People used to leave baked goods on roadsides for the migrating jashtans and would watch them at night when the lights of their torches would all move in line and then suddenly disappear. The same is witnessed in the Kitsunebi (Fox Fire) phenomena of Japanese mythology where migrating foxes create a trail of fire by torches which, just like that of the jashtans, appears at night and slowly increases in magnitude before vanishing.

Khapisi (Night Hag)

Khapisi is a demonic entity that is the Chitrali version of the famous night hag found in many cultures and mythologies. The Chitrali Khapisi sits on the chest of a sleeping person and renders one unable to breathe and move. It shares similarities in its name to the Pashtun night hag (Khapasa) and whilst the Khapasa is said to lack fingers, the Khapisi lacks the senses of speech and comprehension and is deaf and dumb.

Feru-tis (Hearth Faery)

The Feru-tis is a special type of a fairy, rather a pixie, which inhabits the hearths in Chitrali households. Hearths go by the name of diraang in the Chitrali language (Khowar) and are a site of utmost importance in Chitrali culture due to the climate of the Hindu Kush mountains, and the hearth's relation to the fairy itself is explained in the fairy's name since the word 'feru' translates to 'ash' and 'tis' is the mere sound produced by crackling embers of wood. The Feru-tis is a harmless fairy that does not indulge in many activities but is credited to be mischievous at times and often steals the small belongings of the family members. Though hearth goddesses such as Hestia in Greek mythology or the Brigid of Celtic lore are quite well known, the remarkable similarities that the Feru-tis fosters are with Gancanagh of Irish mythology.

Astonishingly, both Gancanagh and Feru-tis are recorded to be small pixie-like faeries who dwell in hearths. Much like Feru-tis, Gancanagh is also notorious for mischievous exploits and pranks, and above all, Gancanagh too prefers the main hearth which was located in the center of the Irish cottages, much similar to the traditional Baipash room of the Chitralis where the hearth preferred by Feru-tis has a central position.

Halmasti (Celestial Hound)

Halmasti is a demonic hound that occupies a position of sheer notoriety in Chitrali mythology and is associated with the heavens, as evident by its name, halmasti meaning 'thunder'. It resembles a large wolf in appearance and has a coat of dark red fur with long appendages and a large muzzle, and it mostly appears in places where either a child is born or a corpse is washed before burial. Neither place should be abandoned for seven days and nights; rounds of recitation of the Quran were conducted around corpses and lullabies were sung to newborns. People were more cautious around newborns since the Halmasti could physically harm them and that is why babies were not abandoned for a moment, but if an extreme need arose, a weapon of iron would be placed under the newborn's pillow for protection.

The Halmasti is certainly the most peculiar creature of Chitrali mythology because it shows not only how folklore develops differently in different regions but also how Chitral, at the juncture of the Turkic, Iranic, and Sinitic worlds, shows a synthesis of all three. The origin of Halmasti was in ancient Sumer where it was known as a female demon known as Littu which was adopted by the Semitic people as Lillith and spread all over European mythology, mainly as a child snatcher, whereas the Western Iranic tribes adopted it by the name of 'Al' or 'Hal', another child-snatching witch. In the Turkic world, a female spirit known as Al-Basti hunts guilty souls from whom the Chitralis most probably inherited it. The Chitralis adopted its Turkic name but not its description as a female entity, rather the Chitrali description of the Halmasti mirrors the Tiangou (Heavenly Dog) which was a celestial hound of ancient Chinese mythology that used to descend from the skies with thunderous lightning to eat the sun and moon to cause eclipses and also imparted petulance in small children.

Quqnoz (Phoenix)

Chitrali mythology also has the concept of a phoenix-like large mythical bird which has more than 300 pores in its beak. It lives for 500 years, and nearing the end of its life, it ascends a pile of wood where it sings a song, which ignites the wood. When the first rain of spring takes place, the first droplet lays forth a new egg from the ashes. It is said that all music of the Chitrali language originates from the mythical Quqnoz. Both its name and the description are close to the Quqnos of ancient Persian mythology, though the Persian version has 100 pores in its beak and lives longer.

Chumur Deki (Iron-legged Steed)

Another mythological creature of Chitrali mythology is a horse with iron legs, which is only identified with the noise of its iron hooves colliding with the ground and is an omen of bad luck, bringing despair to those who see him. The creature seems to be an indigenous product of the ancient Chitrali lifestyle where the caravans and those who took part in transregional trade with Central Asia dreaded a meeting with this demonic creature. It could also very well be the product of the superstitions held by the traders or possibly the fate that befell some of them during such trips.

Banshee of Shoghort

The banshee also makes an appearance in Chitrali folklore, albeit as a singular entity deep in a valley called Shoghort inside of an old fort. It has been noted in literature spanning more than a century that the fort is inhabited by a banshee whose wails can only be heard before the death of a king. Certain writers have also identified it to be the above-mentioned fairy princess born to a Chitrali ruler 400 years ago, who does this to show her sympathy to her father's kingdom.

Nihang (Aquatic Dragon)

Other creatures of fame in Chitrali Mythology are the lake-dwelling dragons, known as Nihang, the name being derived from the Persian word nahang for crocodiles but classically used for various sea creatures. Perhaps a better term for these creatures would be winged serpents, also found in many parts of mainland Pakistan. These gigantic scaly creatures were known for their golden manes, and one of them inhabited a lake in Chitral where it terrorized the local populace, but its reign of terror ended when one day an ancient warrior stood up against it using a double-hilted sword.

The description of the Chitrali dragon shows yet another link between the East and the West because the physical description of the dragon appears to be completely East Asian with the thick furlike mane, aquatic habitat, and a long slender serpent-like body, however, unlike the Eastern dragons, the Chitrali dragon appears to be a malevolent creature bent on keeping a reign of terror upon its vicinity. Lake dwelling creatures seem to be an ancient belief of the Hindu Kush mountains. The 7th-century CE Chinese traveler Xuanzang spoke of a lake-inhabiting dragon in the region, and though the location of this lake is not known for certain, it has been identified by some as Lake Dufferin on the border of Chitral with Afghanistan.

Deo (Fire Giant / Will-o'-the-Wisp)

Deo's are demonic creatures and one of the four principal giants of Chitral which inhabit desolate regions such as caves and dwell in the extreme wilderness. Contrary to other giants of Chitrali mythology, the deo often makes appearances amongst humans with a peculiar ability to convert into glowing orbs of fire which can be often seen in the paths of travelers. They appear in front of travelers but do not allow for the travelers to approach them because they quickly vanish. Their appearance and actions both make them appear to be closely linked to the will-o'-the-wisps of European medieval folklore, but the shape-shifting property seems intrinsic to the western Himalayas.

Nang (Aquatic Cyclops)

The Nang is one of the few principal giants of Chitrali mythology who are known for their underwater habitat beneath lakes and their one central eye, giving them the appearance of a cyclops. Indeed, the name itself seems to be a corruption of the above-mentioned term 'nihang' for sea creatures, and in a classic way of giant tales, the Nang owns a large quantity of underwater treasure and often terrorizes princes and princesses in its palace. The association of lakes, giants, and princes seems to be another intrinsic quality of the northern mountain ranges of Pakistan where just south of Chitral lies Lake Saif Ul Malook, named after the protagonist of a tale involving a giant and a prince.

Barzangi & Barmanu

The demon giant Barzangi is a creature of phenomenal power; it was said to arrive with extreme rainfall and hailstorms. The etymology of its name is difficult to decipher, however, it probably stems from the Persian words 'barez', meaning 'high' or 'distinctive', and 'zangi', meaning 'dark', translating to 'Dark Giant'. It inhabits caves and desolate areas and feasts on other living creatures; it is said to devour a man with such ferocity that not even a drop would fall to the ground before it moves in on its human prey. There are tales of local folk heroes fighting the Barzangi which provide only one absolute way of defeating the giant: decapitation. However, the Barzangi in a very hydra-like manner retains the ability to regenerate its head seven times.

The Barmanu is the most famous giant in Chitral. It is the indigenous version of the Himalayan yeti.

Conclusion

Although the poor preservation of written sources has rendered it impossible to reconstruct the ancient Chitrali belief system, we do have a meager understanding of how these creatures played a role in the archaic religions of the Hindu Kush because of the Kalasha minority of Chitral who keep the traditional beliefs alive. Over the passage of many millennia, the Hindu Kush has seen many foes, and each has left its mark on the people, which is evident in the rich mythology and folklore that Chitral boasts of.