Black Kettle (Mo-ta-vato/Mo'ohtavetoo'o, l. c. 1803-1868) was a chief of the Southern Cheyenne who became famous as a "peace chief" – seeking peaceful relations with the US government – as opposed to war chiefs such as Roman Nose (Cheyenne warrior). Even so, all Black Kettle's efforts were betrayed, and he was killed in the Washita Massacre in 1868.

He was born a member of the Northern Cheyenne, but, in 1854, married his third wife, Medicine-Woman-Hereafter of the Wotapio band of the Southern Cheyenne, and became one of their chiefs when her father died. He would marry four times and father seventeen children. In his youth, he served in the military society of the Elk Horn Scrapers, fighting the Utes, Pawnee, and other Plains Indians, and was recognized as one who "carried the war pipe" – a great military leader. He was eventually granted the honor of carrying the Cheyenne's Four Sacred Arrows into battle.

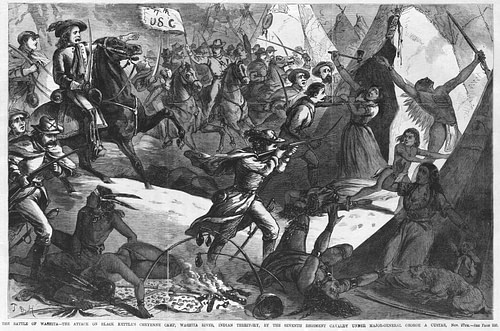

Black Kettle survived the Sand Creek Massacre of 29 November 1864 but lost face to the Dog Soldiers, the military society led, at that time, by Chief Tall Bull (l. 1830-1869) who, like Roman Nose (l. c. 1830-1868), rejected diplomatic efforts with the US government and advocated war. Black Kettle continued to pursue peace with the United States, however, over the next four years until he was killed, along with Medicine-Woman and about 60-150 others at the Washita Massacre/Battle of Washita River of 27 November 1868. He is remembered as a great peacemaker and idealist who believed the best about others.

Early Life & Warrior Status

Little is known of Black Kettle's life before the 1850s. His birth date is usually given as 1803 but sometimes appears as 1807. He was a member of the Suhtai band of the Northern Cheyenne and his father's name was Swift Hawk Lying Down. His mother's name was Sparrow Hawk Woman and he had three siblings. His father was a warrior who taught him to ride and shoot. He was already known as an expert horseman before he was ten years old, took part in his first buffalo hunt at the age of twelve, and fought in his first battle when he was 14.

Before he was 20, Black Kettle was known as a great warrior, regularly leading war parties against other Plains Indian nations, including the Utes and Pawnee. By this time, he was already a member of the Elk Horn Scrapers military society whose chiefs reported to the Cheyenne governing body of the Council of Forty-Four and listened to their advice but, like the other military societies (including the famous Dog Soldiers), were free to disagree with the Council's decisions and often chose their own path.

At some point, he married Little Sage Woman who, in 1854, accompanied him on a raid into Mexico to avenge the deaths of two Cheyenne. On their way back, they were attacked by a large band of Utes and Little Sage Woman fell from her horse. She was taken by the Utes and was never seen again. That same year, Black Kettle married Medicine-Woman-Hereafter, whose father was a chief of the Southern Cheyenne. Black Kettle became a member of her family, leaving the Northern Cheyenne and settling with her people in the region of modern-day Colorado.

Relations with Euro-Americans & Colorado War

After Medicine Woman's father died, Black Kettle was chosen as a chief and became one of the Council of Forty-Four. He had already dealt with the US government by this time through the Fort Laramie Treaty of 1851 and was acquainted with Euro-Americans even earlier through interactions at the trading post of Bent's Fork, established in 1833. Black Kettle was, therefore, already on good terms with White fur traders as he supplied them with buffalo hides and other pelts. His adopted daughter, Magpie, would eventually marry George Bent, the famous Cheyenne-Anglo interpreter and historian, and son of William Bent, the fur trader who owned Bent's Fork.

Black Kettle's cordial relations with White settlers and traders were first tested by the California Gold Rush of 1848, which brought an influx of miners through Cheyenne and Sioux lands. Their wagons and cattle destroyed large swaths of prairie, scattering the buffalo, and making it more difficult for Black Kettle's people to hunt them for food or hides to trade. The White pioneers also brought cholera and other diseases with them, killing many of the Native people of the Great Plains.

Clashes between the Sioux, Cheyenne, Arapaho, and White settlers – as well as between these nations and others of the Great Plains over resources – led to the Fort Laramie Treaty of 1851 which established boundaries for each Native American nation's territories and acknowledged that the United States had no claim to these lands. Black Kettle signed the treaty as a representative of the Southern Cheyenne, securing them lands in modern-day Wyoming, Nebraska, and Colorado, south of the North Platte River.

The treaty was never really honored by the US government and was broken completely in 1858 when the Pike's Peak Gold Rush brought even more White settlers to the region. Tensions between the Cheyenne-Arapaho and the settlers finally resulted in the Treaty of Fort Wise of 1861. Black Kettle was, again, among the delegates representing the Southern Cheyenne at the signing on 18 February 1861. The Dog Soldiers under Tall Bull refused to join the delegates and maintained their position that the only reasonable response to the aggression of the US government was the armed defense of Cheyenne lands.

The Treaty of Fort Wise, like that of Laramie, was also never honored by the US government, leading to the Colorado War (1864-1865). The Cheyenne were led by Black Kettle, Tall Bull, and Roman Nose, among others, allied with the Lakota led by war chiefs including Sioux chief Spotted Tail (l. 1823-1881). Although Black Kettle is frequently referenced in connection with the Colorado War, his role is unclear. It is certain that the Southern Cheyenne took up arms and fought in the conflict, and, no doubt, some people of Black Kettle's band did also. Black Kettle himself, however, was still trying to find a way to live in peace with the invaders.

He was convinced that armed conflict could only end badly for his people and so continued his attempts at negotiations. He may have been part of the peace delegation that met with President Abraham Lincoln in 1863 at which the chiefs were given "peace medals" and, according to tradition, Lincoln presented Black Kettle with the American flag that later flew above the camp at the Washita River, though this claim has been challenged. Even if he was not a member of that party, however, he was still known to be active in seeking peace with the White invaders of his ancestral lands at the same time as the peace delegation's trip to Washington, D.C.

In September 1864, he reached an agreement with John Evans (l. 1814-1897), Governor of Colorado Territory, that he and his people would relocate to the Sand Creek Reservation near Fort Wise (known at this time as Fort Lyon). Black Kettle was promised good land and regular provisions from the fort to help the people settle in; the provisions never came, however, nor any of the other promised supplies.

Sand Creek Massacre/Battle of Sand Creek

The Dog Soldiers under Tall Bull refused to recognize the Treaty of Fort Wise and continued their attacks on wagon trains, trading posts, and settlements. US authorities blamed Black Kettle, claiming that, according to the treaty, he was supposed to keep his people in check. This was a common mistake made by US officials in negotiating treaties in that they believed the chief of a single band within a Native American nation had the power to compel the behavior of chiefs of other bands. The Council of Forty-Four reached conclusions and made recommendations to the chiefs of all the bands of the Cheyenne, but there was no guarantee those chiefs would agree with or follow those suggestions. Black Kettle had no more control over Tall Bull than the governor of one US state today has over the legislative decisions of the governor of another.

The Dog Soldiers were not part of the camp at Sand Creek and Black Kettle was in full compliance with the agreement he had made with Evans, but, on the morning of 29 November 1864, Colonel John Chivington (l. 1821-1894) led the Third Colorado Cavalry in an attack on the village, massacring at least 150 people, mostly women and children. Like many massacres of Native Americans, the engagement was called a "battle" and hailed as a "great victory" until the accounts of US officers who had refused Chivington's order to attack a village of mostly unarmed people, and others present (including George Bent), came to light. Chivington was forced to resign his commission, but no other measures were taken against him.

Black Kettle and his wife escaped the camp and fled with other survivors. The massacre upended the Cheyenne governmental structure as eight of the Council of Forty-Four had been killed. Further, Tall Bull had been proven right when he had told Black Kettle not to trust the White authorities and so the Dog Soldiers now became the dominant power, and their stand for war only intensified. Black Kettle himself now doubted the wisdom of his efforts at peace negotiations, declaring:

Although wrongs have been done to me, I live in hopes. I have not got two hearts…My shame is as big as the earth…I once thought that I was the only man that persevered to be the friend of the white man but, since they have come and cleaned out our lodges, horses, everything else, it is hard for me to believe the white men anymore. (Nozedar, 47)

Still, between 1865 and 1868, Black Kettle continued his efforts to find a way to live in peace with the White settlers. The Sand Creek Massacre had seriously undermined his authority, however, and more Cheyenne were now aligned with warriors like Roman Nose and Tall Bull who continued their attacks on wagon trains, settlements, and individual homes and farms. Their actions contributed to the US military campaign known as "Hancock's War" led by Major General Winfield Scott Hancock (l. 1824-1886), which included the burning of the Cheyenne village at Pawnee Fork on 19 April 1867. All the Cheyenne escaped but lost their homes, personal possessions, clothing, and food supplies. Even so, Black Kettle refused to give up and, again, entered into negotiations with US authorities, signing the Medicine Lodge Treaty of 1867 in October of that year.

Washita Massacre/Battle of the Washita River

The Medicine Lodge Treaty accomplished nothing except to later generate a series of lawsuits brought by various nations against the US government for fraud. The Cheyenne, Sioux, Kiowa, Arapaho, and Comanche bands who were actively engaged in war with the United States were not present, never signed the treaty, and so were not bound by it. Red Cloud's War (1866-1868) was far from over in 1867, and none of the great Sioux warriors, such as Red Cloud (l. 1822-1909), Crazy Horse (l. c. 1840-1877), or Sitting Bull (l. c. 1837-1890), paid any attention to the proceedings. Although seven Southern Cheyenne chiefs, including Black Kettle, signed, these were already men committed to peace. The Dog Soldiers and other Cheyenne military societies did not sign, and so war chiefs like Roman Nose and Tall Bull continued just as they had before.

The charges of fraud had to do with the stated purpose of the treaty – to address grievances of the Plains Indians and injustices – and its actual effect of limiting and even reducing the size of reservations, which cut many nations off from their traditional hunting grounds. General Philip Sheridan (l. 1831-1888), who was not at all interested in Native American grievances, launched a campaign against the Cheyenne, giving Lt. Colonel George Armstrong Custer (l. 1839-1876) complete freedom to do as he pleased in subduing the hostile bands of the Great Plains.

The Medicine Lodge Treaty had moved Black Kettle's band to an encampment on the Washita River in "Indian Territory" (modern Oklahoma). Like many of the other Native peoples of North America who had complied with the demands of the US government, the Southern Cheyenne under Black Kettle were attempting to scrape out an existence in a foreign and inhospitable landscape, relying heavily on provisions from the local fort. As these people were within the boundaries of Indian Territory, they had no reason to fear attacks by US military. Black Kettle flew the American flag over his camp and also had a white flag of truce, which he ordered to be raised immediately at the sight of any approaching US soldiers.

The plan of attack on the "hostiles" devised by Sheridan and Custer was to track them, locate their winter camps, and destroy them, taking the women and children and hanging any warriors. On 26 November 1868, Custer's command came upon a trail, which, according to his Osage scouts, clearly suggested a war party. The markings along the ground indicated only horses and men, not women and dogs, which would have suggested a hunting party. Custer followed this trail to Black Kettle's camp. Who actually made that trail is unknown, but if it was a war party, it could have been any one of many at the time, whether Cheyenne, Kiowa, or another.

Custer had been part of Hancock's campaign and was present at Pawnee Fork when, with the village surrounded, the Cheyenne had still managed to escape. To ensure this did not happen under his command, Custer arranged his troops quietly before daybreak, completely encircling the village, and then ordered the attack. According to some eyewitnesses, the American flag and white flag of truce were flying; according to others, only the American flag was flying as no one was awake to raise the white flag. Either way, as at Sand Creek, there were few warriors in the camp and most of those had been disarmed upon their arrival, and so Custer wound up massacring women, children, and the elderly along with the relatively few men of the camp.

Black Kettle and Medicine Woman were shot in the back and killed while trying to cross the Washita River. Medicine Woman is said to have scolded her husband the previous evening for not moving their camp further so as to be closer to the others on the river and so have greater safety in numbers, and as it turned out, she had been right. US casualties were 21 killed; Cheyenne casualties are numbered around 60-150.

Conclusion

By the time of the Washita Massacre, Roman Nose was dead, killed in September 1868 at the Battle of Beecher Island. Tall Bull would continue the fight until his death at the Battle of Summit Springs on 11 July 1869. The Cheyenne population was reduced further during and following the Great Sioux War (1876-1877). Further resistance was offered in 1878 by the Northern Cheyenne chiefs Morning Star (Dull Knife, l. c. 1810-1883) and Little Wolf (l. c. 1820-1904) but, essentially, Cheyenne power had been broken.

Black Kettle's peace initiative failed only because he was dealing with a government that had no interest in recognizing his rights and so could not be trusted to deal with him fairly. After each broken treaty, he seems to have believed he had been wronged by a single assembly of White representatives, not realizing that they were acting in the interests of those who had sent them. Even after he was betrayed at Sand Creek – where Medicine Woman was shot nine times but managed to survive – he still believed in the basic goodness and decency of the US officials he was forced to deal with.

He remains one of the most admirable figures of 19th-century American history in his refusal, in spite of all evidence that he should, to abandon his efforts at living peacefully with Euro-Americans. As a warrior, he knew how to fight and win but chose, instead, to follow the path of peace, even though that path led eventually to his death at the hands of those he believed, right up to the end, he could trust to stand by their word.