The Shahnameh (“Book of Kings”, composed 977-1010 CE) is a medieval epic written by the poet Abolqasem Ferdowsi (l. c. 940-1020 CE) in order to preserve the myths, legends, history, language, and culture of ancient Persia. It is the longest work by a single author in world literature at a length of 50,000 rhymed couplets, 62 stories, and 990 chapters.

The book relates some of the most famous stories from Persian myth, legend, and history. It was originally commissioned by Mansur I (r. 961-976 CE) of the Samanid Dynasty (819-999 CE), which encouraged the development of Persian literature, and was begun by the poet Daqiqi (l. c. 935-977 CE) who died after writing the beginning. It was completed by Ferdowsi under the Ghaznavid Dynasty (977-1186 CE) which was less enthusiastic but still expressed an interest in the subject.

The work covers the entire history of ancient Persia from the creation of the world to the Muslim Arab conquest of 651 CE which toppled the Sassanian Empire (224-651 CE), the last great Persian Empire of antiquity. The conquest devastated the ancient Persian culture and threatened to completely annihilate it under the Umayyad Caliphate (651-750 CE), but when the Abbasid Caliphate (750-1258 CE) overthrew the Umayyads, Persian culture was again valued and the development of Persian literature and art was encouraged.

Ferdowsi seized upon the interest in the Persian past to create a work that would both honor the past and prevent it ever being lost as it almost had been following the conquest. Although Ferdowsi dedicated himself to the work with the understanding that he would be paid well when it was finished, it is likely he would have written it on his own without patronage in order to create a living landscape of Persian history that people would be able to visit and appreciate long after he was gone.

The poet makes his motivation clear in the work itself when he boldly tells the reader that he will live forever through his work which, in the modern day, has been credited with preserving Persian language, literature, and culture, is the national epic of Iran, and is consistently included among the greatest works in world literature.

Conquest & Revival

The Sassanian Empire, beginning with its first monarch Ardashir I (r. 224-240 CE), worked toward the preservation of the Persian oral tradition by committing scripture, commentary, and other works to written form. Whatever literature may have existed in the earlier Achaemenid Empire (c. 550-330 BCE) had been lost during the conquest of Alexander the Great, and the Parthian Empire (247 BCE - 224 CE) had developed a script to preserve Zoroastrian scripture which existed only in oral form. The Sassanids took the Parthian initiative further and created written Persian literature.

In 651 CE, the Sassanian Empire fell to the Muslim Arabs who then imposed their religion and culture on the conquered. Libraries, temples, and other repositories for books were burned and the Persian culture suppressed. The Umayyad Dynasty maintained this oppression until they were overthrown by the Abbasids with the help of Persian allies. The Abbasid Dynasty recognized the value of Persian culture and encouraged its expression, notably under the Samanid Dynasty which ruled by leave of the Abbasids.

Ferdowsi & the Shahnameh

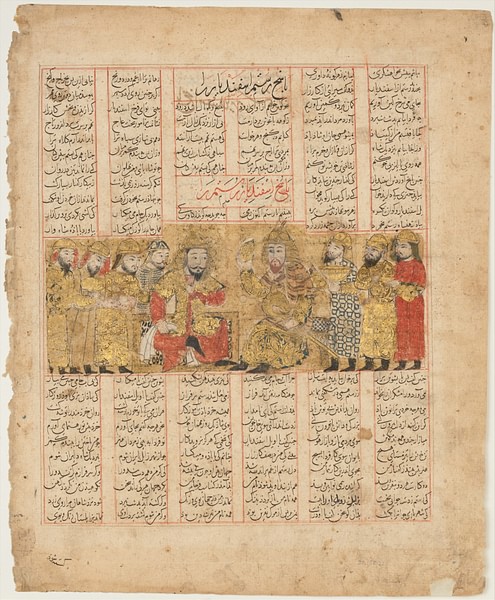

Ferdowsi was not a court poet but was a friend of the influential Abu Mansur who may have encouraged Mansur I to give him the job of completing Daqiqi's work. Mansur I agreed to pay Ferdowsi a gold piece for each couplet he wrote as the work progressed but Ferdowsi, possibly believing at this time that it would not take him very long, requested a lump sum to be paid when the poem was completed. It would take him almost 30 years to write the Shahnameh and, by the time it was finished, Mansur I and the Samanids would no longer be in power and Ferdowsi would have to request patronage of the Sultan Mahmud of Ghazni (r. 999-1030 CE) of the Ghaznavid Dynasty in order to be paid. Ghaznavids did not have the same interest in or appreciation of Persian culture that the Samanids had. Even so, Mahmud agreed to Ferdowsi's request and the poet continued on with his work.

Ferdowsi was so insulted that, after buying himself a beer at a nearby stand, he divided the coins between the beer-seller and the man who kept the baths and then, fearing Mahmud's displeasure at this act, fled the region. His benefactor, Abu Mansur, was dead by this time but, according to Ferdowsi's own account, Abu Mansur's son, Mansur Tusi, continued to help him financially. Even so, Ferdowsi complains bitterly that he had not received what was promised and how, although wealthy associates praised his talent, they gave him nothing in return for it.

He eventually returned to his home city of Tus and most likely lived off the revenue of his family's estates, though this is conjecture as all that is firmly known is that he had an orchard; no other lands are mentioned. Eventually, Mahmud had the correct sum sent to the poet but, as the legend goes, the caravan bringing the gold entered the gates of Tus just as Ferdowsi's funeral entourage was coming out. Ferdowsi's daughter refused the cash, and it was redirected to the construction of a caravansary near the city.

This account is considered legendary because Nezami visited Ferdowsi's tomb and collected the information on the poet over 100 years after his death. Even so, this version of events is suggested by Ferdowsi's own comments throughout the Shahnameh. Ferdowsi is not at all the distanced third-person narrator in the work but periodically inserts himself to make clear a story's moral, lament a character's distress or death, offer advice and, in a number of passages, talk about his life and how he is feeling at the moment. In these personal passages, it is clear that his health was failing and he felt abandoned and ill-used but this did nothing to discourage him from finishing the work.

Overview of Structure & Religious Influences

The Shahnameh, as noted, tells the story of the history of ancient Iran from the beginning of the world through the fall of the Sassanian Empire to the Muslim Arabs. Scholar Homa Katouzian comments on its structure:

Shahnameh is made up of three cycles, the Pishdadiyan, the Keyaniyan, and the Sassanian. The first, beginning with the dawn of man and the Pishdadiyan, is pure mythology. The next cycle describes the Iranian kingdom of the Keyaniyan, the long story of a heroic age in which myth and legend combine to produce an ancient epic. The first two cycles of Shahnameh are centered on eastern Persia whereas the third cycle is centered on the south and west. It mixes history with legend while providing an account of the history of the Sassanian monarchy, the last Persian dynasty before the Arab conquest. (19-20)

The Pishdadiyan, Keyaniyan, and Sassanian refer to dynastic houses and each of these informs the action of the stories concerning the Mythical Age, Heroic Age, and Historical Age respectively. Ferdowsi repeatedly addresses the subject of the monarchy, illustrating the problems which arise from the abuse of power and, conversely, the greater good that comes from acting in the interests of others. From the first cycle through the third, the danger of thinking too highly of one's self, and treating others poorly, is highlighted through tales of prideful, unjust monarchs or nobility losing the divine grace of the gods (which legitimized their rule) though selfish acts which disregarded the good of the people they were supposed to serve.

Although there can be no doubt whatsoever that Ferdowsi was a sincere Moslem…he makes no attempt to include any elements of the Qur'anic/Moslem cosmology in his poem, nor does he attempt to integrate the legendary Persian chronology of the material at the opening of his poem with a Qur'anic chronology. Unlike other writers who dealt with similar material, and who did attempt to intertwine the two chronologies, he simply ignores Islamic cosmology and chronology altogether and places the Persian creation myths center stage. (xix-xx)

The work is also informed by a belief system, often referred to as a Zoroastrian heresy, known as Zorvanism, which was especially popular during the Sassanian period. Traditional Zoroastrianism held that there was one supreme God – Ahura Mazda – who struggled constantly with his adversary – Angra Mainyu (also known as Ahriman), a created being. This belief made no provision for the origin of evil because all things – including Ahriman – had come from the all-good Ahura Mazda.

Zorvanism solved this problem by making Zorvan, the embodiment of Infinite Time, the supreme deity who gave birth to the twins Ahura Mazda and Ahriman. Setting Time as the supreme god, however, encouraged a fatalistic approach to life because there was no placating Time as one could a deity. A number of the stories in the Shahnameh reflect this belief in implacable fate where, no matter how great and powerful the hero, there is no escape from the destiny set in motion by Time.

Famous Stories

The poem begins with the creation of the world, the first humans, and the establishment of kingship. The greatest of these kings is Jamshid (also given as Yima elsewhere) who provides humanity with the gifts of civilization. He is able to accomplish all his great feats because he has the farr, the divine grace given by the gods, which makes a man a king. In time, however, he begins to think more highly of himself than he should and has a great throne built for himself, which elevates him above the world. He becomes “ungrateful, proud, forgetful of God's name”, boasts of his supremacy, and so loses the divine grace (Davis, 7-8). The loss of the farr, and Jamshid's decline, opens up the opportunity for Ahriman to spread chaos and destruction, which he does in the form of the usurper king Zahak, the embodiment of evil, who murders his father, overthrows Jamshid and establishes a 1,000-year tyranny which is finally overthrown by the hero Fereydun.

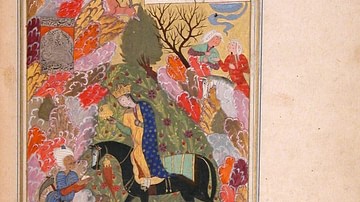

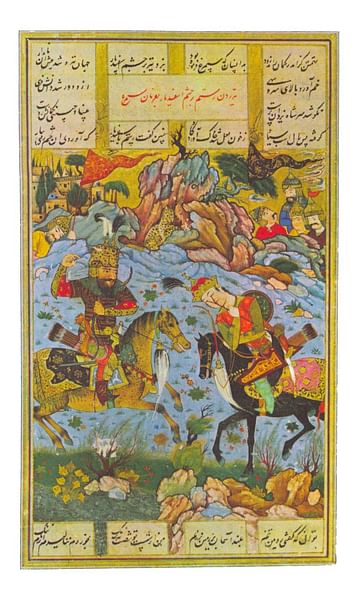

There are many more stories in the cycle of the Mythic Age, which Ferdowsi develops completely before moving on to the Heroic Age. This cycle is the longest of the Shahnameh and features some of the most famous figures such as Rustum (also given as Rostom or Rustam), his son Sohrab, and the good prince Siyavash. The Keyanian cycle takes its name from the title of king or chief – key – and the most famous of these is Key Kavus, the often unjust ruler of Iran whose ongoing feud with the kingdom of Turan informs this section. Rustum, born of the princess Rudaabeh and the hero Zal, emerges as the champion of Iran. He is invincible, riding his great stallion Rakhsh into battle and on various adventures.

Sohrab vows to end the war between Iran and Turan and find his father at the same time. He sets off with an army to kill Key Kavus and then plans to return and overthrow Afrasiyab and restore peace. Afrasiyab, however, knows that Sohrab is Rustum's son and makes sure that, whenever they meet, they will not recognize each other. Sohrab has become as great a warrior as his father and ably defeats Kavus' troops until, finally, he meets the champion of Iran in single combat, not knowing it is Rustum. Rustum has no idea he even has a son and attacks the champion of Turan. Sohrab fights well but is finally struck down and defeated. As he is dying, Sohrab learns he has been killed by the great Rustum and tells him that he is his son but that he should not grieve because fate decreed all that had happened.

The tale of Rustum and Sohrab is among the best-known in the Shahnameh but another, equally popular, is the story of the good prince Siyavash, son of Key Kavus. Kavus' wife, Queen Sudabeh, is Siyavash's step-mother and falls in love with him. She propositions him, telling she will have Kavus murdered and she and Siyavash will rule together. He rejects her and Sudabeh fears he will reveal her to Kavus, so she goes to her husband, after tearing her clothes and smearing herself with blood, and accuses Siyavash of raping her. Siyavash maintains his innocence and so Kavus decrees a trial by fire. Siyavash is ordered to ride through an enormous conflagration which will destroy him if he is guilty but leave him untouched if innocent. Siyavash rides into the flames and emerges on the other side unscathed. Kavus then orders Sudabeh executed but Siyavash intercedes, and she is spared. Siyavash later goes to Turan, where he is married to a princess who will give birth to their son, Key Kosrow, and is later unjustly executed by Afrasiab.

Conclusion

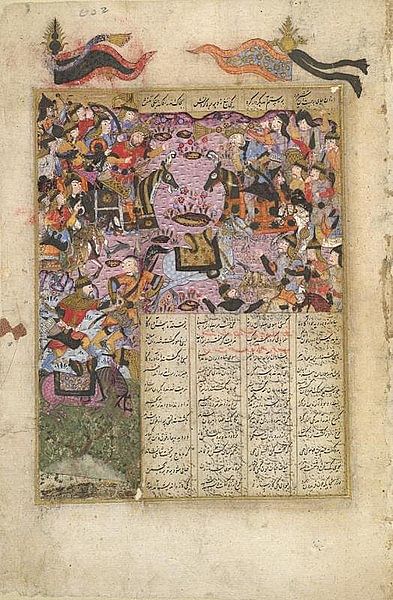

The section closes with a great battle in which Rustum is killed but predicts, before dying, a greater age to come and hope for the future. The third cycle begins with a brief mention of the Arsacids (Parthian Empire) before telling the story of the Sassanians and their struggle against the invading forces of the Muslim Arabs.

Ferdowsi's chronology of events and history of the empire is accurate though scholars have noted that the depiction of the Sassanians and Muslim Arabs is romanticized, depicting the one along the same lines as Iran and the other as Turan from the Heroic Age. The Sassanians are finally defeated, and Ferdowsi ends the tale with the line, “After this came the era of Omar, and when he brought the new faith, the pulpit replaced the throne” (Davis, 961) in reference to the Caliph Umar and the arrival of Islam in Persia.

Ferdowsi concludes his poem with a few lines on his enduring fame as its creator: “I've reached the end of this great history/And all the land will fill with talk of me…And men of sense and wisdom will proclaim,/When I have gone, my praises and my fame” (Davis, 962). This prophecy came to pass as his work was embraced early on by the people of Iran (by the 13th century CE, it had already been copied and images from the poem adorned various structures) eventually becoming the country's national epic.

The German poet Goethe (l. 1749-1832 CE) and English poet Edward Fitzgerald (l. 1809-1883 CE), through their respective works West-Eastern Divan (a collection of poems inspired by the Persian master poet Hafiz Shiraz) and The Rubaiyat of Omar Khayyam, piqued Western interest in Persian literature and translations of Ferdowsi's work brought the story to an even wider audience. Over a thousand years after its completion, the Shahnameh continues to be admired and Ferdowsi's name, as he predicted, stands equal in stature to any of the great writers of world literature.