The Battle of the Ruhr or the Ruhr Air Offensive (March-July 1943) was a sustained bombing campaign by the British and the United States air forces against the industrial heartland of Germany during the Second World War (1939-45). The offensive included strikes against industrial cities and specific targets such as steelworks, armaments factories, transportation networks, and the Ruhr dams. Great damage was done to Germany's heavy industry, but given that production recovered and even increased, the battle is considered a draw.

Area Bombing of Germany

The Ruhr Valley area was responsible for 60% of Germany's industrial output. The area was such a tempting target it had already been attacked in May 1940, but only by a small force of around 100 bombers, which had not met with any great success. This time it would be different. The commander-in-chief of the Royal Air Force (RAF) Bomber Command was Arthur Harris (1892-1984). He firmly believed that the war could be won by bombing the enemy into submission, that is by smashing war-industry targets and civilian morale. Harris was given support at the highest level to try out the 'bomber's dream' of winning the war by air power alone. To make the dream a reality, Harris had at his disposal such four-engined heavy bombers as the Lancaster bomber, capable of carrying a bomb load of 14,000 lbs (6,350 kg), the Short Stirling, and Handley Page Halifax.

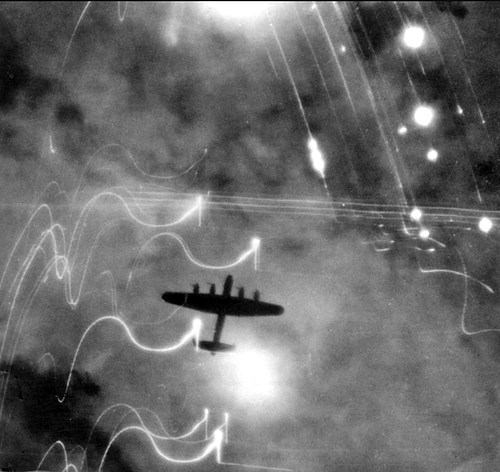

The thousand-bomber raid on Cologne in 1942 had shown what a large attack force could achieve. Such a number of planes, flying to the target in a single formation known as the bomber stream, could overwhelm the enemy defences – anti-aircraft flak guns and fighter planes like the Messerschmitt Bf 109, which patrolled the entire area that had to be crossed to reach the Ruhr. Bombers could not have a fighter escort over Germany at this period in the war given the limited fuel range of planes like the Hawker Hurricane and Supermarine Spitfire, and so the best cover for slow-flying bombers was darkness.

The RAF had tried precision bombing – hitting specific small targets – but these required more dangerous daylight operations (and clear weather), and, given the limited bomb-aiming technology of the time, the results had been very poor, most bombs dropping several miles from the intended target. Such were the difficulties, many planes failed to even find the target. The idea of area bombing (aka carpet bombing) was to have a central aiming point for the first bombers and then successive bombers worked their way outwards, either by intention or accident. Consequently, a large area of the target was more uniformly bombed. The 90-minute area bombing of Cologne destroyed some 15,000 buildings and 1,500 factories. In addition, the city's utility supplies and various transport networks were all severely damaged. There were 469 deaths, 5,000 people were injured, and 45,000 people were made homeless. With 41 aircraft lost, the RAF considered the raid a success. The strategy of area bombing by a large force could now be applied to the Ruhr Valley.

Identifying Targets

Bomber Command had some particular problems to deal with for the Ruhr offensive. The first problem was knowing where the targets were and what their significance to the German war effort was. As the historian M. Hastings points out "intelligence about enemy industry remained a weakness of the strategic air offensive from beginning to end" (16). The second problem was that the Ruhr was "the most heavily defended region of Nazi Germany" (Hastings, 187). Back in 1939, Hermann Göring, head of the Luftwaffe, the German airforce, had boldly stated that "The Ruhr will not be subjected to a single bomb. If an enemy bomber reaches the Ruhr, my name is not Herman Göring!" (Liddell Hart, 196).

The Ruhr Valley was protected by around 200 flak batteries. Each battery consisted of either six or eight 88-mm (3.5 in) guns, many with radar capability. Some guns were even mounted on trains to follow the bombers. Due to this dense network of anti-aircraft guns and countless searchlights, Allied bombers soon gave the Ruhr the ironic nickname of 'Happy Valley'.

Another problem was that the Ruhr Valley was so heavily industrialised that there was constant smog in the skies above it, which impeded the bomb aimers but also made it difficult for the navigators to even find the target area. There were some technological aids available, but at this stage in the war, they were few and unreliable. Some of the newer bombers were equipped with Gee radar equipment, which could help them find the target. In order to help the non-Gee-equipped bombers, the Gee-equipped ones would go in first and drop flares to mark the target. The problem with Gee was that it could be jammed by specially equipped enemy fighters. Pathfinder squadrons, first used by the RAF in August 1942, helped mark the route to the target and the target itself by dropping bundles of pyrotechnic candles or parachute flares. Another strategy was to have some bombers first drop incendiary bombs to start fires that would mark the target for subsequent bombers loaded with high explosives.

Another useful device was H2S (aka H2X), a ground-search radar for when targets were completely obscured visually. A problem with H2S was that it sent out signals, which revealed the plane's position to the enemy, and it could be jammed using counter-signals. From 1943, the RAF used the Oboe guidance system, which sent signals from Britain to help guide bomb drops. Oboe had a limited range but sufficient to cover most of the Ruhr Valley.

March

The first big offensive came on the night of 5 March 1943 against Essen, an industrial city with one particular cherry the RAF would like to take a bite of: the massive Krupps steelworks. Three waves of bombers, a total force of 442 aircraft, were sent in. 56 bombers suffered mechanical failures and had to turn back. Those that remained took 38 minutes to damage about one-third of the steelworks and around 50 factories. 44 bombers failed to hit Essen with their bomb loads. 14 bombers were shot down. Essen was hit again on 12 March.

April

Duisburg had important railway marshalling yards, which connected the Ruhr to other parts of Germany, and the large Thyssen steelworks. Duisburg was bombed three times in April. Essen was struck again at both the beginning and the end of the month. One RAF pilot, the Canadian Jim Weaver, describes Essen's defences:

On every trip there would be variable amounts of flak and some fighters about, depending on the target. The large German cities were the most heavily defended, and any trip to Essen – or indeed anywhere in the Ruhr – was like going into 'the Valley of the Shadow of Death'. The favourite crew expression when asked about flak on one of these trips was 'You could get out and walk on it'.

(Neillands, 214-5)

Meanwhile, the United States Army Air Force (USAAF) in the form of the Eighth Air Force based in Britain, was continuing to hit its own selected targets during the day. These included the Focke-Wulfe aircraft factory in Bremen, struck by a force of 115 bombers on 17 April, and the Ford factory in Antwerp, hit in May by 18 B-17 Flying Fortress bombers. All through the Battle of the Ruhr other targets were consistently hit to avoid a concentration of enemy defences in any single area. This meant the USAAF's participation in the Ruhr offensive was limited. Other operational limits were the high risk of daylight missions (the USAAF's preferred strategy) and the unsuitability of its aircraft for night bombing given their design and much smaller payload than the RAF's Lancasters.

May

The RAF also hit many other targets in Germany throughout the offensive, notably Berlin, Munich, Nuremberg, and Stuttgart. Specific Ruhr targets hit in May included Duisburg and Düsseldorf, each subjected to a force of around 300 Lancasters. Dortmund was hit by 862 bombers in a single massive raid that destroyed the city's Hoesch steelworks. Over 1,700 civilians were killed or injured. At the end of May, 719 bombers struck Wuppertal and made 100,000 residents homeless overnight; 3,400 people were killed or injured.

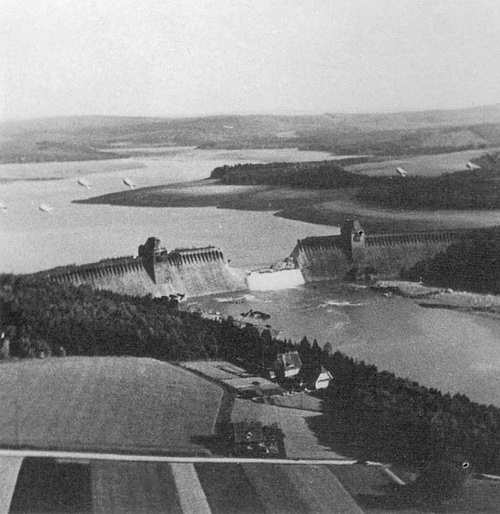

May saw one of the most famous RAF operations of the war: Operation Chastise. This was a raid on the Ruhr dams with the idea that the breached reservoirs would flood the valleys below, knocking out countless armaments factories, hydroelectric plants, and steel and coal works. To damage the dams – which were slim targets when seen from the air and which were protected by torpedo nets – a special bomb had to be developed. Barnes Wallis (1887-1979) invented the 'bouncing bomb', a barrel-shaped rotating bomb that could be dropped on the reservoir and which would skip along the surface until it hit the dam wall, sank to a sufficient depth, and then exploded. Three dams were a priority: Möhne, Eder, and Sorpe.

Guy Gibson (1918-44) led his specially-trained 617 Squadron of 19 Lancasters to the Ruhr basin on the night of 16 May. The Möhne and Eder dams were breached, but the Sorpe remained intact. Eight Lancasters did not return home. The enormous flooding from the breached dams did seriously disrupt Germany's industries, but these recovered production within six months. The Möhne dam was repaired in 18 weeks, just in time to capture the autumn rains, which refilled the reservoir. Around 1,300 civilians were killed in the floods caused by Operation Chastise, a figure which includes 500 Ukrainian women working as forced labour. The operation would be considered a war crime today (so classified by the Geneva Convention), but it was milked for its propaganda value and gave battered Britain a much-needed fillip that the nation was finally taking the war to Germany. There were other positive consequences for the RAF. The raid showed that specially trained crews could hit small but strategically valuable targets. The operation had also successfully tried out a new idea, which was to have a master bomber (in this case Gibson) who could stay in contact with his other planes using VHF radio and so better conduct the attack and make the bombing much more accurate. The RAF would use master bombers for many more raids in the battle of the Ruhr.

June

Despite the progress made in bombing accuracy, Harris was not pleased with the results of the operations so far, as he wrote in this circular to bomber aircrews:

The battle of the Ruhr is now in its third month and will go on until it has been won. It will be won when the Ruhr ceases to produce munitions of war… Unfortunately a number of bombs are still falling 2, 3 and 5 miles from the aiming point, and this is delaying the victory.

(Hastings, 278-9).

In the May raid on Düsseldorf, most of the bombers had missed the target. The city was struck again on the night of 11 June, this time by a force of 783 bombers. The consequent fires spread over an area of over 14 square miles (40 square kilometres). 20 military installations and 77 factories were damaged. 1,200 civilians died, and 140,000 people were made homeless. On the night of 12 June, Bochum was hit by over 500 bombers. Another choice target that June was the steel and coal works of Oberhausen. On 22 June, Mülheim was hit by 557 aircraft. On 24 June, Wuppertal was struck again, effectively destroying the city's industrial capacity and killing or injuring over 4,000 civilians. USAAF bombers successfully hit the synthetic rubber works at Huls, also on 22 June.

The Ruhr simply had too many possible targets, and the RAF did not have the planes to attack them all or even a group of them repeatedly, a weak point of the whole campaign. To stretch the German defences, Cologne was hit in a raid on 15 June.

July

The bombs kept falling, but the Germans were growing more proficient in their defence. They used strategies to trick the bombers into hitting useless targets. Dummy factories were built, smoke bombs clouded the skies above, and false fires were set up in fields to make it look like the factories were located there.

The RAF was now finding the short summer nights a problem and demands were being made on it to contribute in other theatres of the war such as bombing targets in Italy ready for an invasion, and, to help the battle of the Atlantic, lay mines at sea and hit the German U-boat bases in northern France. These demands limited how often specific Ruhr targets could be hit. Harris had been correct that what he needed was not 1,000 bombers but 6,000.

The final and 44th operation of the Battle of the Ruhr was the second raid on Gelsenkirchen, which had important synthetic oil refineries, on the night of 9 July. Symptomatic of the Sisyphean task Bomber Command had set itself, the Gelsenkirchen refineries were fully operational again in August.

Assessment

In all, the RAF had launched 23,000 missions against the Ruhr. Aircraft losses had begun to increase proportionally towards the end of the battle, largely due to an increased concentration of German fighters being directed over the area. In total, Bomber Command lost 1,000 aircraft and around 7,000 men in the battle. Heavy damage was inflicted, but repairs were made. For these reasons, the historian R. Neillands states: "the Battle of the Ruhr was a draw" (222).

The Ruhr raids were scaled back, largely because the damage done was overassessed, because aircraft were needed elsewhere, and because Harris remained convinced that the bombing of industrial cities was the best way to win the war. The German Minister of Armaments Albert Speer (1905-81) was surprised but grateful that more heavy raids did not follow on the Ruhr after July. Speer was also surprised by the resilience of Germany's industry and workers:

The British air raids began to have their first serious effect on production…These air raids carried the war into our midst…Neither did the bombings and the hardships that resulted from them weaken the morale of the populace. On the contrary, from my visits to armaments plants and my contacts with the man in the street I carried away the impression of growing toughness. It may well be that the estimated loss of 9 percent of our production capacity was amply balanced out by increased effort.

(Speer, 381)

The real problem for the RAF was that bombing factories came with inherent restrictions on success, as here noted by Neillands:

The bombing certainly damaged a large number of Ruhr factories, but in the years since 1939 it had become clear that an industrial target needed constant bombing if it was to be kept out of production. Even the most accurate raid rarely achieved total destruction of the target and, unless the raid was repeated, the damage would quickly be made good, the machines and jigs be replaced, and production be resumed. It was also possible to move the plant to some safer location, but it was less easy to move and rehouse the hundreds of thousands of skilled workers.

(215)

From November, Bomber Command concentrated on the bombing of Berlin despite area bombing becoming an increasingly contentious issue for the number of civilian casualties. There was still, too, much debate as to the strategic value since morale and cities were badly beaten but not smashed.

Germany's war industry had certainly been held back by the Ruhr offensive. Even if German production figures continued to rise, these figures would have been greater without the bombing. There were also less direct consequences. Germany was obliged to divert huge resources to defending factories and cities, men and equipment that could have been used on the Eastern Front against Russia, for example. There was a home propaganda value, too. Before a land invasion of Continental Europe was possible, hitting Germany by air was one of the few ways the Allies could directly hurt the enemy, an enemy that had hurt Britain countless times in exactly the same way, for example during the London Blitz of 1940-1.

From the summer of 1943, the Combined Bomber Offensive saw a much greater collaboration between the RAF and the USAAF. The June Pointblank directive issued by the Allied Combined Chiefs of Staff declared that the priority should now be German aircraft factories to ensure air superiority could be achieved prior to the D-Day Normandy landings planned for the summer of 1944. This was now crucial since "between November 1942 and July 1943 German fighter production increased from 400 to over 800 aircraft per month" (Neillands, 150).

There followed many more raids on Germany and occupied Europe, which ranged from city-bombing like Operation Gomorrah, which utterly devastated Hamburg at the end of July and the beginning of August 1943, to precision bombing like the Schweinfurt-Regensburg raids in August-October 1943, which aimed to destroy Germany's capacity to produce ball bearings needed for armaments. The Allied air offensive continued right through the war as the strategy of area bombing was repeated to hit transport networks in the Ruhr, oil supplies, and yet more cities, with Duisburg hit in a 'thousand-bomber' raid in October 1944 and, most infamously of all, the bombing of Dresden in 1945.