The Allied strategic bombing of Germany during World War II (1939-45) involved British and U.S. bomber planes attacking industrial cities, factories, railways, airfields, and dams. Over 600,000 civilians died as a consequence. The campaign aims included destroying Germany's capacity to produce weapons; disrupting transport networks and oil, steel, and coal supplies; destroying the German air force; and breaking civilian morale.

Secondary goals of the strategic bombing campaign by the Royal Air Force (RAF) and United States Army Air Force (USAAF) included boosting home morale that Germany was paying a price for its invasion of Europe and bombing of Britain. Another aim was to demonstrate to the USSR that the Western allies were assisting the Soviet campaign on the Eastern Front. Some Allied commanders believed that the war could be won using air power alone, avoiding a land invasion. As it turned out, Germany fought on, and only a land operation from the east and west would finally win the war.

Why Did the Allies Bomb Germany?

The official military objectives of the strategic bombing of Germany are indicated in several directives formulated by the Allied Joint Chiefs of Staff. The Casablanca conference in January 1943 noted that the objective of the bombing offensive was:

The progressive destruction and dislocation of the German military, industrial and economic system, and the undermining of the morale of the German people to a point where their capacity for armed resistance is fatally weakened.

(Dear, 196)

The Casablanca objective was amended by the Pointblank Directive of June 1943. This emphasised the importance of destroying German fighter plane production in readiness for the D-Day Normandy landings (Operation Overlord) planned for the summer of 1944. Before the Allies could contemplate a land invasion of Continental Europe they had to achieve air superiority or their armada would be destroyed. The Quebec conference of August 1943 reaffirmed the objectives of Casablanca and Pointblank but removed the objective regarding civilian morale.

Other aims of the bombings, perhaps not officially expressed but there, nonetheless, were to show the British and American public and Russia that something was being done to take the war to Germany. In the absence of a land attack on Germany, bombing was the next best thing. As the German Armaments Minister Albert Speer (1905-1981) noted, the air war became "a second front", one that absorbed men and machines which otherwise could have been used on the Eastern Front against Russia and in coastal defences in northern France.

The Bombers

The RAF included many personnel from the British Empire such as Australia, New Zealand, and Canada, as well as French, Polish, and American crews, amongst others. The USAAF was represented by the Eighth Air Force, based in Britain, commanded by Ira C. Eaker (1896-1987), and in action in Europe from August 1942. Bombers were deployed by both air forces over Germany and many other targets in occupied Europe, Italy, and the Mediterranean.

The RAF aircraft used to drop bombs on Germany included the four-engined Avro 683 Lancaster bomber, capable of carrying bomb loads of 14,000 lbs (6,350 kg). Other four-engine bombers deployed included the Short Stirling and the Handley Page Halifax. For defence against fighter planes like the Messerschmitt Bf 109 (Me 109) and Fock-Wulfe 190, bombers had machine-gun turrets at the nose, back, and tail of the aircraft. The best USAAF bomber was the B-17 Flying Fortress. Although carrying less than half the bomb load of a Lancaster, the B-17 was bristling with 13 machine guns, all with a heavy-punch calibre of 0.50 inches (12.7 mm). The USAAF's second-best but most numerous bomber was the reliable Consolidated B-24 Liberator.

Bombers usually dropped first explosive bombs and then incendiaries to set ablaze the ruins. Special bombs included the 12,000-lb (5,443-kg) 'Tallboy' and the 'Grand Slam', which weighed 22,000 lbs (10 tons), designed to penetrate concrete and create such a massive explosion it replicated the effects of an earthquake.

USAAF crews were volunteers for the bombing missions. Due to the risks involved, flyers were given a maximum of 25 missions per combat tour, later extended to 35. The RAF crews served for 30 missions, but many repeated the cycle before the war was over. All crews were young, anyone in their thirties was typically given the nickname of 'grandad'.

The Bombing Strategy

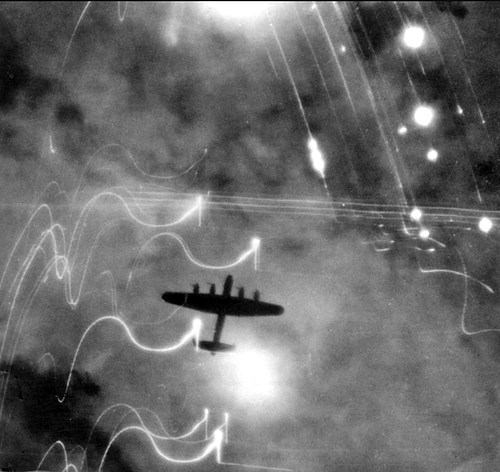

The RAF initially conducted bombing raids in daylight since this meant the targets could be more easily found and identified. However, it soon became clear that the slow-flying bombers were too vulnerable to enemy anti-aircraft defences and fighter planes. Allied fighters like the Supermarine Spitfire and Hawker Hurricane did not have the fuel range to protect bombers over Germany. Consequently, the RAF switched to night-time bombing when it was much more difficult to find and attack bomber planes. Unfortunately, this also meant that bombing accuracy was seriously reduced. The basic physics involved with non-guided missiles was itself an impediment to accuracy. Dropped bombs were still travelling at the speed the aircraft had been, which meant they were dropped in a curve towards their intended target. The RAF eventually found out just how wildly inaccurate the bombing had been thanks to the Butt report of August 1941. It turned out that only one in three planes ever dropped a bomb within 5 miles (8 km) of the target. Unfavourable weather, unreliable or simply inadequate radar equipment, and the havoc caused by enemy air defences meant that precision bombing – hitting a specific target like a small group of factory buildings – was more a hope than a reality. In addition, bombs had to be dropped even if the original target could not be found since the bombers consumed two-thirds of their fuel on the trip out, and the only way to return to base was in a much lighter plane.

To improve accuracy, the RAF adopted a new strategy: 'area' bombing ('blind bombing' or ‘carpet bombing'). This involved dropping bombs over a larger area but still hoping to hit factories and strategically important targets. The unfortunate consequence of area bombing was that many civilians were killed or injured as a consequence. It is important to note that cities targeted in this way were always industrial cities deemed crucial to the German war effort. Another innovation to help make the bombing more effective was to have the bombers fly in very large groups, assembling in a ‘bomber stream' long before they reached the target area. Such a large concentration of bombers overwhelmed the enemy's defences and ultimately led to fewer proportional losses per raid. The idea of using one thousand bombers in a single raid was championed by the commander-in-chief of RAF Bomber Command, Arthur Harris (1892-1984). Harris believed bombing alone could win the war by forcing Germany to surrender if hit hard enough.

When the USAAF joined the strategic bombing campaign in Europe, the attempt was made once again to conduct daylight raids on specific vital targets in Germany. The USAAF commanders believed that they could avoid the heavy losses the RAF had experienced because the B-17 bomber was more heavily armed and because they would fly in a much tighter formation where machine gunners could protect their neighbours and hit approaching fighters with a barrage of fire. In the end, USAAF bombers typically flew in wings of 54 planes. Nevertheless, the German fighters soon learned that the weak spot of the bomber plane was the nose, and so they attacked head-on and avoided all the other machine guns, which were mostly placed to fend off an attack from the rear. There were also significantly more losses from mid-air collisions due to the close proximity of the planes in their tight formation. With many missions losing more than 10% of the force, daylight raids proved just as dangerous and unsustainable as they had done for the RAF. The USAAF's response was to scale back raids until a long-range fighter escort became possible, which finally arrived in March 1944 in the form of the P-51 Mustang.

The RAF and USAAF often worked independently, selecting targets that each thought important. It is something of a myth that the RAF bombed cities and the USAAF bombed specific militarily important targets. In reality, both forces pursued both types of targets. This was especially so with the Combined Bomber Offensive (CBO) when the two forces coordinated very closely to hit the same target. Typically, USAAF bombers struck by day and the RAF by night, keeping up a constant pressure on the defences. This was seen, for example, in Operation Gomorrah of July-August 1943 when Hamburg was hit around the clock. There were disagreements. Some commanders wanted to bomb only transport networks, some only cities, and others only fuel supplies. In the end, anything and everything was attacked to hurt the German war effort from every direction.

The Technology

The air war was a technological race as attackers and defenders devised new ways to outwit each other. Certain targets were well-defended by batteries of powerful 80-mm (3.1 in) anti-aircraft guns, many of which were radar-controlled. The bombers had to run the gauntlet of fighter defences spread across northern Europe where the bombers had to cross.

Finding the target was far from easy, particularly at night. From 1943, the RAF used the Oboe guidance system, which sent signals from Britain to help guide bomb drops, but the range was limited to northern Germany. Many times bomber crews have recorded that, unable to find the intended target, they instead bombed alternatives, including towns.

Once over the right target, the next problem was to find the right place to drop the bomb loads. Some planes had Gee radar equipment that helped in this area. However, Gee could be jammed by specially-equipped enemy fighters. The RAF also used Pathfinder (PFF) squadrons, which dropped Target Indicators (TIs) so that pursuing bombers could sight the target better. Each TI was a bundle of 60 pyrotechnic candles of prespecified colours (to differentiate from German decoy flares), which lit the target area by descending slowly for three minutes. In cloudy weather, parachute flares were used instead. Pathfinders could light the route to the target, too. VHF radio between aircraft and the use of a 'Master Bomber' who could guide the other planes to the target were first successfully employed on Operation Chastise (see below).

USAAF bombers used the Norden bombsight but still required clear visibility of the target, a rare occurrence given that the view was frequently obscured by smoke from fires below, flak, and clouds. For completely obscured targets, the H2S ground-search radar system was used (H2X to the USAAF), although this could also be jammed by signals sent out from enemy planes, and it revealed the position of the bomber to enemy listening devices.

Window (US name: Chaff) technology was used for the first time in Operation Gomorrah. Window was essentially foil-covered strips dropped in their thousands to create a cloud of metal that caused havoc with the German radar defences and the gun-aiming devices of anti-aircraft weapons. The defenders saw only a blizzard of white dots on their screens and could not differentiate the planes from the foil strips.

The Targets

Targets for the bombing offensive included anything of importance to the German war effort. Ports, shipyards, railways, armaments factories, steelworks, bridges, and dams were all targeted. Such targets were very often in the middle or suburbs of cities. Industrial cities like Cologne, Hamburg, Berlin, Nuremberg, Stuttgart, Essen, Bremen, Düsseldorf, and Dresden were all struck, often repeatedly. The concentration of Germany's heavy industry in the Ruhr area led to that entire region being targeted in the battle of the Ruhr (March-July 1943).

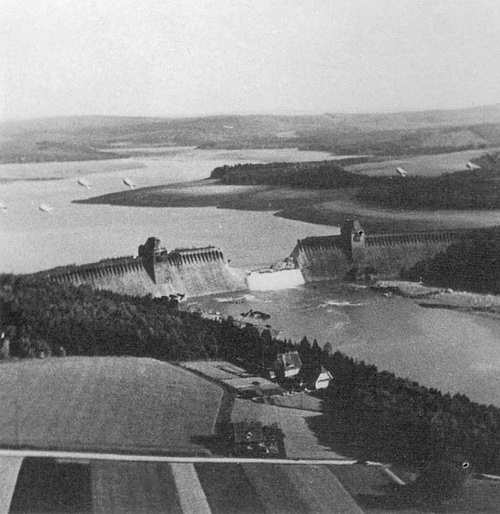

One famous strategic raid involved the 'Dambusters' of Operation Chastise on 16 May 1943. In an attempt to flood the Ruhr Valley factories, which were supplied by several large reservoirs, a bomb was devised that could be dropped on water which then bounced along until it struck a dam. The 'bouncing bomb' was devised by the engineer Barnes Wallis (1887-1979). Three dams were particular targets: Möhne, Eder, and Sorpe. The Möhne and Eder were breached causing massive local flooding, and the operation was of great propaganda value to Britain.

In August and October of 1943, the USAAF attacked crucial industrial targets in the Schweinfurt-Regensburg raids. Hundreds of bombers struck the ball bearings factories at Schweinfurt and the Messerschmitt aircraft plant at Regensburg. Deemed a partial success in that enemy production was seriously affected, almost 150 bombers were lost, too high a loss rate to be sustained. Unfortunately for the Allies, Germany had reserves of ball bearings, which meant it could continue with supplies until the factories were repaired.

The Damage

The RAF launched 23,000 missions against the Ruhr alone. Dortmund's Hoesch steelworks were destroyed, and so were the synthetic oil refineries at Gelsenkirchen. So many factories were hit, Speer estimated German industrial production fell by 9%. In Germany as a whole, Speer estimated the loss in possible industrial production due to bombing as 20-30%.

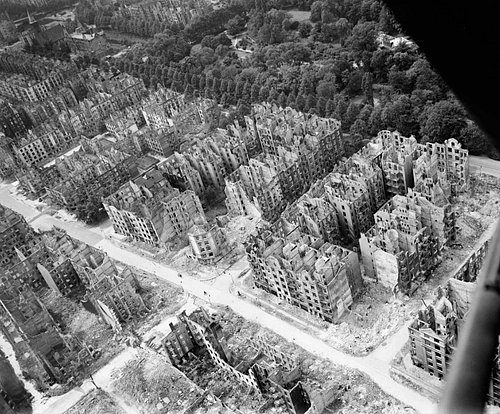

The consequences of the bombing raids on cities were catastrophic. In the thousand-bomber raid on Cologne in 1942, 1,455 tons of bombs were dropped on the city in 90 minutes; 1,500 factories and 15,000 buildings were destroyed, and 45,000 people were made homeless. The casualties were relatively few as the air raid shelters beneath the city did their job. A year later, in the terrible firestorms in Hamburg caused by Operation Gomorrah, 580 armaments factories were destroyed, but 46,000 civilians died in the process. Of course, many of the victims worked in the city's factories. It is believed that after the raid 27 fewer U-boats were built in the Hamburg docks because there were insufficient skilled workers available. Even so-called 'precision bombing' very often inflicted huge collateral damage since a wave of bombers tended to bomb further and further from the area hit by the first bomber, a phenomenon known as 'creepback'.

A single raid on Wuppertal made 100,000 residents homeless overnight. A raid on Düsseldorf made 140,000 people homeless. The 'Dambuster' raid caused flooding that killed 1,300 civilians. In the bombing of Berlin (November 1943 to March 1944), 400,000 people lost their homes, and many thousands were killed. Through 1944, the Allies were dropping on average 3,000 tons a day of bombs on Germany. In the bombing of Dresden in 1945, four RAF and USAAF raids, made to support the Eastern Front then just 100 miles (160 km) away, killed 30,000 civilians and flattened the city.

Assessment

Severe disruption was caused, but to keep up that disruption, the bombing had to be repeated every few weeks. This was impossible to do everywhere given the bombers available, and so very often production recovered and even improved thanks to the use of double shifts and forced labour. In addition, both the RAF and USAAF faced constant demands for their services in other theatres of the war.

The RAF lost almost 9,000 aircraft in the bombing of Europe. It is estimated the RAF and USAAF each lost around 53,000 personnel in the bombing campaign (died, wounded, or taken as prisoners of war). This was the worst proportional loss rate in any of the three armed services for both Britain and the United States. The number of German civilian deaths is estimated at between 600,000 and one million.

In one important objective, the bombing campaign was deemed a success by the Allies: the destruction of the Luftwaffe (German Air Force). So many German pilots were killed during the air war and Germany's oil supplies were so reduced that the Luftwaffe ceased to exist as an operational force. The Allies achieved air superiority and so were ready for D-Day. Other aims were partially achieved such as causing the diversion of men and equipment for air defence and creating transportation bottlenecks. In 1941, Germany engaged 65% of its forces in the east, but in 1944, this figure was reduced to 32%. Air defences involved 10,000 anti-aircraft guns requiring millions of shells and hundreds of thousands of soldiers to operate.

It is the bombing of German cities that remains the most controversial aspect of the bombing of Germany during the war. The lack of evidence that civilian morale was being broken and concern over high civilian casualties contributed to seriously discrediting the idea of area bombing even before the war ended. It was proven that bombing alone, at least in Europe with the resources available, could not win the war.

For many Allied commanders, Dresden was certainly a bombing too far. As the London Blitz had shown, civilian morale and the will to fight could be very resilient indeed against repeated bombing. Even if civilians could have been demoralised in Nazi Germany, they were not living in a democracy but in a dictatorship where dissent could very quickly end in imprisonment or death. In short, a demoralised civilian population did not mean a regime change would follow. Even if it was not the intention to kill civilians, the bombing of industrial cities could be classified as a war crime today. The deliberate bombing of such targets as dams and public utilities with obvious fatal consequences for civilians is more definitely classified as a war crime by the Geneva Convention.