The Avro 683 Lancaster bomber was a four-engine heavy bomber flown by the Royal Air Force and allies during the Second World War (1939-45). Lancasters were particularly used in nighttime bombing raids and could carry the heaviest bombs ever dropped in WWII. Lancasters dropped the 'bouncing bombs' on several Ruhr dams in Operation Chastise, the 'Dambusters' raid of May 1943.

Design Origins

The Lancaster began on the drawing board as a two-engine aircraft until it was decided to make a four-engine bomber. It was born from the two-engined Avro 679 Manchester medium bomber. The problems experienced by the Manchester's engines and frame during operations in 1940 allowed the Avro designers to attempt a bigger and better bomber. Four engines meant the plane could fly heavier bomb loads further and increased its chances of returning home if one or more engines failed or were hit by enemy anti-aircraft fire or fighters. The first prototype, called Manchester III, was completed in January 1941. Design changes were made, and the first bomber was successfully tested at RAF Waddington in Lincolnshire. Avro gained a contract for over 1,000 planes, now called Lancasters, but many more orders soon followed. By October, the first Lancasters were in active service, but it was not until March 1942 that the first Lancaster squadrons were in operation. Ultimately, over 7,350 Lancasters were built. The Lancasters eventually saw service in the Royal Air Force (RAF), the Royal Australian Air Force (RAAF), and the Royal Canadian Air Force (RCAF).

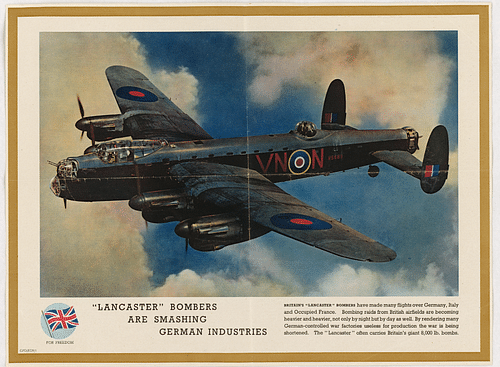

The Lancaster outperformed its slightly older predecessors the Short Stirling and Halifax, both of which also had four engines. The Lancaster had superior handling and could carry a much heavier bomb load, although the other two aircraft remained contemporaries in terms of active service. Aircraft expert D. Mondey remarks that "no one would dispute the statement that the Avro 683 Lancaster was the finest British heavy bomber of World War II, few would even argue against the premise that it was the finest heavy bomber serving on either side during the conflict" (28). The plane became the workhorse of RAF Bomber Command and a firm favourite with crews for its manoeuvrability, even after suffering damage from enemy fire, which happened all too frequently in the highly dangerous activity of bombing deep into enemy territory.

Specifications & Crew

The Lancaster had a length of 69.5 ft (21.18 m) and a wingspan of 102 ft (31.09 m). The bomber was first fitted with four 12-cylinder Rolls-Royce Merlin engines, each capable of 1,145 hp (854 kW); these engines were regularly upgraded over the years, and sometimes alternative manufacturers were used. The Lancaster's engines each powered a three-bladed propeller. The top speed was 287 mph (462 km/h) with a cruising speed of 210 mph (338 km/h). It had a range of 2,530 miles (4072 km) and could fly to an altitude of 24,500 feet (7470 m). The bomb load could reach 14,000 lbs (6,350 kg) of multiple bombs or a single gigantic bomb of 22,000 lbs (almost 10 tons), known as a 'Grand Slam' and the heaviest bomb dropped during the war by any air force. Weapons for defence included eight 0.303-inch (7.6 mm) Browning machine guns distributed in the three turrets: rear (x4 guns), dorsal (x2), and nose (x2). Some later aircraft had 0.50-inch (12.7 mm) machine guns in the tail turret. There was a second glass nose for the bomb-sighter located below the nose gunner's dome. Lancasters were equipped with the latest equipment as it came along during the war, for example, the H2S scanner radar for blind bombing. The most common colour scheme was a black undercarriage and lower half of the fuselage with dark brown and dark green camouflage on the upper surfaces.

The Lancaster bomber had a crew of seven, who very often had trained together, which meant they were a close-knit group of men, sometimes of mixed nationalities such as British, Canadians, New Zealanders, South Africans, and Australians. There was the pilot (who was also the captain), second pilot/flight engineer, navigator, wireless operator, bomb-aimer (who was also the front gunner when required), mid-gunner, and finally the rear gunner, who occupied the most dangerous, isolated, and certainly coldest spot on the plane. In case the plane had to be abandoned there were parachutes and an inflatable dinghy.

Operations

Lancasters bombed strategic sites like factories, an early example being the raid in August 1942 on the MAN factory producing diesel engines for U-boats in Augsburg in southern Germany. This was a daylight raid since the target was no bigger than a football pitch. It involved 12 Lancasters flying especially low, but seven aircraft were lost either before or at Augsburg due to enemy fighter attacks. Those that made it dropped their loads of four 1,000 lb (450 kg) bombs; 17 bombs hit the target. The raid was a success in terms of destroying its target and Squadron Leader John Nettleton received the Victoria Cross medal. However, it was clear to the RAF's Bomber Command that, due to the losses, unescorted daytime bombing raids could not be sustained (the role was later taken over by the USAAF with similar heavy losses).

Initially, small groups of bombers found it very difficult to hit their targets, only one in three ever dropped a bomb within five miles (8 km) of the target. Nighttime flying, unfavourable weather, unreliable or simply inadequate radar equipment, and the havoc of aerial warfare with deadly fighters and concentrated anti-aircraft batteries meant that hitting a specific target like a small group of factory buildings became more a hope than a reality.

Bomber Command changed tactics and grouped bomber squadrons into large forces and sent them against varied targets. Lancasters were now being used for more indiscriminate bombing raids designed to destroy civilian morale. This was the strategy of 'area' bombing (aka 'blind bombing') on German cities as well as targets in Italy and occupied Europe. Major raids on German cities included the bombing of Berlin, Cologne, Dresden, Essen, Hamburg, Nuremberg, and Stuttgart.

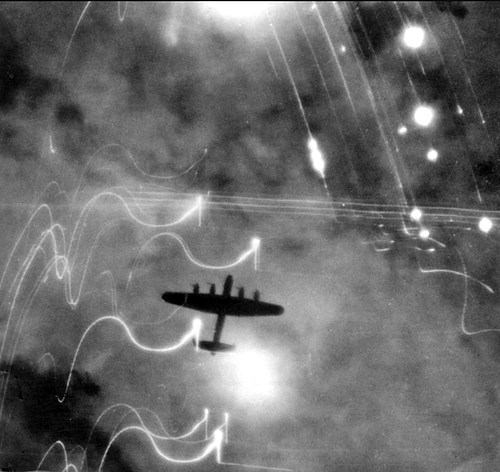

Another tactical improvement was getting the bombers to work better together when over the target area. The bombers, often numbering several hundred and sometimes up to 1,000, had their target identified by a first wave of light bombers dropping fire bombs, then the Lancasters went in and dropped first explosive bombs and then incendiaries to set ablaze the ruins. Cities were often well-defended. The bombers had to run the gauntlet of fighter defences and flak batteries – many radar-controlled. Some flak batteries were even put on trains that could be moved to hit a known flight of bombers from the ground. The number of casualties on the ground of these area bombing raids was enormous, but the effect on morale was minimal, just as it had been when the German Luftwaffe had bombed British cities earlier in the war. Nevertheless, Bomber Command continued its strategy of area bombing.

Famous as a heavy bomber, the Lancaster did perform other duties such as laying mines and operating as a pathfinder for other bombers. There were eventually 14 Lancaster pathfinder (PFF) squadrons, which dropped Target Indicators (TIs) so that pursuing Lancaster bombers could sight the target better. Some TIs were bundles of 60 pyrotechnic candles of pre-specified colours (to differentiate from German decoy flares), which lit the target area by descending slowly for three minutes. In cloudy weather, parachute flares were used instead.

Lancasters with crews still in training were frequently used to fly diversionary routes to confuse the enemy while Lancasters loaded with bombs operated elsewhere. Another diversionary tactic performed by Lancasters was to drop Window, strips covered in metal foil, which interfered with German radar systems. By the spring of 1943, the combination of diversionary squadrons, better radar systems, improved radio communication between bomber crews, jamming devices, and pathfinder TIs greatly improved the effectiveness of the bombing raids, as indicated in the following official report from Bomber Command for the Barmen-Wuppertal raid in eastern Germany at the end of May 1943 by a force which included 272 Lancasters:

611 aircraft, out of a force of 719, attacked the Barmen district of Wuppertal with very great success. The fire-raising technique was effectively employed, as a complement to ground marking, resulting in the best concentration yet achieved by the Pathfinder Force. Immense damage was caused in the town, covering over 1,000 acres and affecting 113 industrial concerns, as well as totally disrupting the transport system and public utilities.

(Spick, 26)

A famous bombing raid given a specific objective again involved Lancasters. This was an attack on the German battleship Tirpitz, sister ship to the battleship Bismarck. Tirpitz was in northern Norwegian waters near Tromsø when it was attacked on 12 November 1944. The ship was sunk by a specially designed bomb, the 12,000-lb (5,443 kg) 'Tallboy'.

Another specialised bomb was the Capital Ship Bomb, shaped like a turnip and designed to pierce armour. This bomb was used in the attack on the aircraft carrier Graf Zeppelin and battle cruiser Gneisnau on the Polish coast in August 1942. The Lancasters failed to hit the target in this raid.

Even bigger than 'Tallboy' was the 'Grand Slam' bomb, designed to penetrate concrete and create such a massive explosion it replicated the effects of an earthquake. On 14 March 1945, a 'Grand Slam' was dropped on the Bielefeld Viaduct and destroyed it. In all, Lancasters dropped 41 'Grand Slams' during the war.

The 'Dambusters' Raid

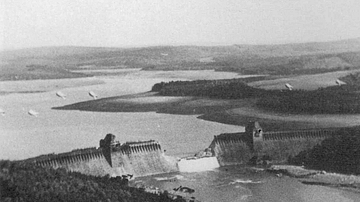

Lancasters were involved in one of the most famous raids of the war, the 'Dambusters' of Operation Chastise. In an attempt to flood an area of the Ruhr Valley factories in Germany, a bomb was devised that could be dropped on water and which then bounced along until it struck a dam, that area having quite a number of large reservoirs. The 'bouncing bomb', codename 'Upkeep', was devised by the engineer Barnes Wallis (1887-1979), who had also designed the Wellington bomber and who would go on to design Tirpitz's nemesis 'Tallboy'. The 9,250 lb (4,200 kg) bouncing bombs (technically mines) were designed to detonate below the surface tight up against the dam wall. These bombs were carried by Lancasters of No. 617 Squadron based at RAF Scampton in Lincolnshire, which had trained extensively using the new bomb over a period of six weeks. The leader of the highly experienced 19 crews was Wing Commander Guy Gibson (1918-44). Five dams were targeted, but three were a priority: Möhne, Eder, and Sorpe. In order to drop the spinning bombs at the required height (too high and the bombs would destruct prematurely, too low and they would not bounce sufficiently), the Lancasters were fitted with two lights fixed to the underside of the plane which were angled to create a merger of the beams precisely 60 ft (18.3 m) below the aircraft. In addition, the pilots had to drop the bomb at a flying speed of 240 mph (386 km/h).

Other adaptions to the dambuster Lancasters included the removal of the nose turret and the bomb doors. The installation of VHF radios so that Gibson could communicate with and direct his squadron was another innovation. The daring raid took place on the night of 16 May 1943. Both the Eder and Möhne dams were breached; the earthen Sorpe dam received direct hits but remained intact. Deemed a success, Gibson was awarded the Victoria Cross. The cost was high. Eight of the 19 Lancasters did not return home, 53 men were killed, and three who were shot down became prisoners of war. On the German side, the tidal waves from the breached dams spread across the valley below for 50 miles (80 km) flooding over 100 factories, several coal mines, and countless homes. More than 1,300 civilians died in the floods.

The damage inflicted by the Dambusters was repaired in a few months, and, if anything, the raid's greatest success was to highlight the advantages of precision low-flying bombing on specific targets by highly trained and handpicked crews, something Bomber Command would pursue with success for the rest of the war. Indeed, No. 617 Squadron and many others were responsible for hitting many key targets like major armaments factories, oil plants, naval bases, and transport infrastructure.

Assessment & Legacy

As the war came to a close, Lancasters were used to support the new and ever-expanding Western Front after D-Day in June 1944. The last Lancasters to fly as a squadron in the war were 514 Squadron in September 1944. According to Mondey, during the war, Lancaster bombers "flew more than 156,000 sorties and dropped, in addition to 608,612 tons of high explosive bombs, more than 51 million incendiaries" (32).

The air war waged by Bomber Command in Europe remains controversial. The indiscriminate bombing of civilians had questionable results. At the time, though, bombing raids were seen as one of the very few ways Britain could take the war to Germany. The defeats had been many, and it was not until the United States upped its involvement in the war that the Allies could even begin to contemplate a physical landing on Continental Europe.

The bombing campaigns of which the Lancasters were such an important element had another, often overlooked consequence. Such was the effect of bombing on Germany's industry and the consequent necessity to better defend it, the German Armaments Minister Albert Speer (1905-1981) described the air war as "a second front", one which absorbed men and machines which otherwise could have been used on the Eastern front against Russia.

The Lancaster's successor was the four-engine Avro 694 Lincoln, which had a longer range and higher altitude capability. Developed in 1944, the Lincoln had a longer fuselage, greater wingspan, and heavier guns. Too late for active use in WWII, the Lincoln did see service in Malaysia and Kenya. After the war, some Lancasters ended up as reconnaissance planes in the French navy, some were used for flight tests, and others were converted for civilian transport when they were known as Lancastrians. There was even a Lancaster used for rescue at sea that could drop a lifeboat. In February 1954, the last British Lancaster to be in service was decommissioned.