According to UNESCO, an estimated three million shipwrecks are scattered in the oceans’ deep canyons, trenches, and coral reefs and remain undiscovered. These shipwrecks preserve historical information and provide clues about how people lived in the past. The term ‘underwater cultural heritage’ refers to traces of human existence and activity found on ancient sunken ships or retrieved cargo such as bronze statues and priceless artworks.

The Spanish treasure galleon, Nuestra Señora de Atocha, is the world’s most valuable shipwreck, estimated to be worth over USD 400 million. It was part of the Tierra Firme fleet of 28 ships bound for Spain from Cuba in 1622 and carried the Spanish Empire's wealth onboard – creamy pearls from Venezuela, glittering Colombian emeralds, and over 40 tons of gold and silver. The Atocha sailed into a hurricane off the coast of Key West, Florida, and sank. Its riches were discovered in 1985 by famed treasure hunter Mel Fisher (1922-1998).

There are countless virtual maritime museum displays, but let us take a look at five shipwrecks with interesting stories to tell.

Vrouw Maria

The Vrouw Maria was an 18th-century Dutch koff ship that sank in Finnish waters on its way to Saint Petersburg in Russia. In September 1771, the vessel left its home harbour of Amsterdam and entered the Danish channel of Öresund on 23 September. The Sound Toll Register recorded detailed information about ships and cargoes that entered the Danish Strait and listed the Vrouw Maria as ‘Dutch ship no. 508.’ Its cargo was noted as sugar and textiles, cheese and butter, books and teas for Russian nobility, as well as 27 valuable paintings bought for Empress Catherine the Great (1729-1796) from the Dutch merchant Gerrit Braamkamp (1699-1771). The paintings are estimated by art valuers today to be worth around €1.5 billion (USD 1.78 billion) and were to be included in The Hermitage collection.

The question of ownership of the Vrouw Maria and its cargo immediately arose with four countries claiming rights: Russia because the cargo was en route there; Sweden, because the area where the ship was found was under Swedish rule in the 18th century; the Netherlands since it was a Dutch vessel; and Finland, which now owns the islands of the Archipelago Sea. It is an important question because whose history does a shipwreck represent? Does the Vrouw Maria represent common European or Dutch cultural heritage?

In 2012, the Finnish Maritime Museum put together a virtual reality exhibition (below) that allows visitors to experience Vrouw Maria’s sinking and inspect parts of the shipwreck.

Downloadable maps are available that show the plan of the Vrouw Maria. You can also visit the Vrouw Maria Maritime Museum, where you will find a detailed list of the cargo. For the adventure seekers, take a deep dive and explore the shipwreck.

Melckmeyt

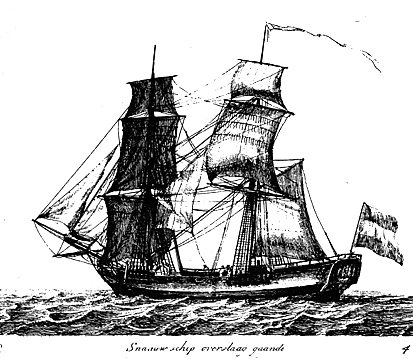

The Melckmeyt (“milkmaid”) is known as the Dutch smuggler’s shipwreck. It was a 33-metre-long (108 feet) Dutch fluyt but flew a Danish flag because, at the time of its sinking in October 1659, it was illegal for the Netherlands to trade with Iceland (which was then ruled by Denmark). Icelandic commerce was controlled strictly by the Danes, but the Dutch saw an opportunity to provide Icelanders with the goods they desired, such as grain and ceramics. The Dutch sailors of the Melckmeyt posed as Danish crew.

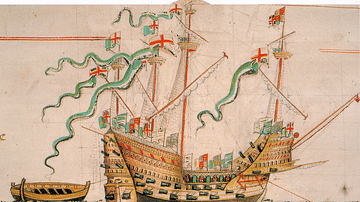

The fluyt (three-masted ship) was the favoured vessel of the Dutch East India Company because it was built exclusively for trade, lightly constructed, and swift on the oceans. It could not outrun a terrible storm on 16 October 1659, however, and the ship sank off the remote Icelandic island of Flatey.

The Melckmeyt is Iceland’s oldest shipwreck, and it was discovered in 1992, impressively preserved thanks to Iceland’s icy waters. A digital reconstruction of the ship is available for anyone to explore and includes Johannes Vermeer’s (1632-1675) famous painting, Milkmaid, on the stern. It can be viewed by using a virtual reality headset such as Google Cardboard or on a computer or smartphone. Users can click and drag to move around the shipwreck.

Few wrecks of fluyts have been found, which makes this underwater archaeological find significant. Around 300 pieces of ceramics, mostly Delftware, were excavated along with tin plates. The shipwreck highlights the period of Icelandic economic history when Denmark ruled the island and dominated maritime commerce.

The London

The London was a 76-gun Cromwellian warship that blew up after a gun powder explosion in March 1665. It was on its way from Chatham Dockyard, sailing up the Thames toward Gravesend. The ship was being mobilised to take part in the second Anglo-Dutch war (1665-1667), but as 17 of its cannons were being prepared for a gun salute, a gun powder explosion and resulting fire killed 300 crew. The London also carried many women, who were presumably on board to farewell the men who would be fighting.

There are no newspapers from that time period to record the event. The first edition of the London Gazette would not come out until November 1665, but diarising was an important way of recording observations and events, so we have Samuel Pepys's diary (1633-1703) to turn to. At the time, Pepys was Clerk of the Acts to the Navy Board, and his diary for 8 March 1665 recorded:

This morning is brought me to the office the sad newes of “The London,” in which Sir J. Lawson’s men were all bringing her from Chatham to the Hope, and thence he was to go to sea in her; but a little a’this side the buoy of the Nower, she suddenly blew up. About 24 [men] and a woman that were in the round-house and coach saved; the rest, being above 300, drowned: the ship breaking all in pieces, with 80 pieces of brass ordnance. She lies sunk, with her round-house above water.

The London sank in the Thames, resting in the thick silt. It was one of three completed ‘second-rate’ vessels ordered for the English fleet, built in Chatham in Kent in 1656. In 1658, it carved its name into history as part of the fleet that set sail for the Netherlands to collect Charles II of England (1630-1685), restoring him to the throne.

The shipwreck was discovered in a busy shipping lane in 2005 when a diving group happened upon the site, and its national importance was recognised when it was given protection under the Protection of Wrecks Act in 2008.

Artefacts that have been excavated so far point to how people lived on board the 17th-century ship: beeswax candles, dozens of leather shoes, a copper alloy spoon similar to today’s soup spoons, bronze weapons, handspikes, a sundial, beer tankards, and signet rings. In 2015, an extremely rare wooden gun carriage was recovered from a depth of 20 metres (65 feet). Warmer waters and temperatures bring wood-boring sea worms into waters where many shipwrecks lie, including The London, but you can take an educational deep-dive tour of the wreck.

Shipwrecks of Lake Champlain

Lake Champlain, located between New York and Vermont, is the sixth-largest freshwater lake in the United States. It is 201 kilometres (125 miles) long and 19 kilometres (12 miles) at its widest point and is home to more than 300 shipwrecks that are well-preserved, thanks to the cold water. Due to COVID-19, the Lake Champlain Maritime Museum moved online and, like many museums, is finding new ways to engage with communities.

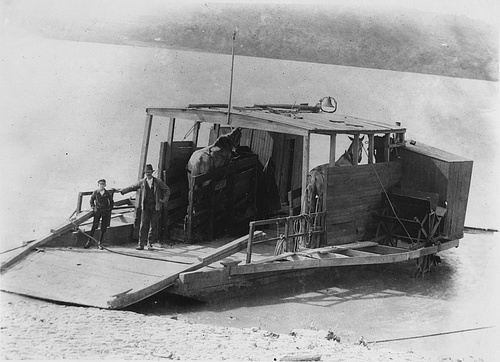

Two of the more interesting wrecks are the Horse Ferry and the Phoenix. Both vessels highlight the importance of commercial navigation and commerce on the lake during the 19th century. In 1983, an almost intact horse-powered boat or ferry was discovered in Burlington Bay. Known as the Burlington Bay Horse Ferry, it is an example of the type of vessel that was a popular form of transportation across the lake between Vermont and New York from the 1820s to the early 1860s.

The Phoenix is another wreck lying at the bottom of Lake Champlain. It was a 44.5-metre (146 feet) commercial steamboat built in 1815 by the Lake Champlain Steamboat Company.

The Phoenix’s claim to fame is twofold: it transported President James Monroe (1758-1831) when he travelled the region in 1817, and it caught fire and sank north of Colchester Shoal on 4 September 1819, becoming one of the earliest steamboat wrecks in US history. A lighted candle in the galley most likely caused the fire. Of the 46 passengers, six perished. The two paddlewheels dropped to the bottom of Lake Champlain and were discovered in 2020, but the remains of the Phoenix, with its white oak and iron hull, still lie at an inky depth of around 33 metres (110 feet). Take a tour of the steamboat wreckage with the Lake Champlain Maritime Museum.

The Monterrey Shipwrecks

The Bureau of Ocean Energy Management (BOEM) in the United States recently launched its Virtual Archaeology Museum. The online museum features five shipwrecks complete with 3D models, maps, and videos. The Blake Ridge wreck is off the North Carolina coast, while the other four are submerged at the bottom of the Gulf of Mexico, where only remotely operated submersibles can explore and survey.

Three of those four ships lie at a depth of around 1310 metres (4,300 feet). They are known as the Monterrey Shipwrecks or Monterrey A, B, and C. It is the deepest wreck ever excavated in North America. Despite exploration with deep-sea vehicles, it is not known where the trio was headed or their country of origin. Monterrey A (which was discovered by Shell Oil in 2011) was an early 19th-century, 25.6-metre (84 feet) wooden-hulled, copper-clad vessel carrying five cannons and crates of muskets.

Little is known about the vessels, but Monterrey A was a fast, topsail schooner and possibly an armed privateer, escorting the Monterrey B as its prize. A cargo of hides and pottery excavated from the wreck suggests it may have originated in Mexico. Monterrey C carried no cargo and was fitted out for a transatlantic voyage.

The early 1800s was a tumultuous time in history: Mexico had gained independence from Spain, Texas declared its independence from Mexico, and France was busy selling Louisiana. The time was ripe for privateers. Galveston Island (off the Gulf coast) was home to the swashbuckling Jean Laffite (c. 1780 - c. 1823), a French privateer. He established a 1,000-strong privateer colony called Campeche in 1817 and received commissions from Spain, Mexico, and the United States.

A watery grave was the unfortunate fate for the three ships. Exploration has revealed an anchor was ripped from one of the ships, with the most plausible explanation being a violent storm hit the Gulf of Mexico. All shipwrecks are time capsules and tell the stories of their crew and passengers. Retrieved so far from the Monterrey Shipwrecks are over 60 well-preserved artefacts, including leather-bound books, tallow, eyeglasses, liquor bottles, decanter, fabric, ceramic jar, telescope, double-sided ivory brush, and octants.

Explore anchors, chainplates, a ship’s stove, and more at the BOEM virtual museum, or take a deep dive and see the Monterrey Shipwrecks and hear archaeologists interpret findings at the site.

The ocean floor is a museum, which can provide vital evidence about how humans lived and traded in the past, went to war, or shipped slaves. With virtual shipwreck tours, you can now glimpse moments in time.