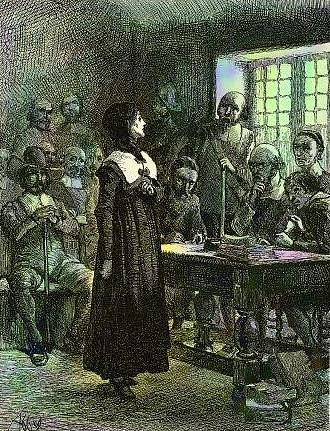

Anne Hutchinson (l. 1591-1643 CE) was a religious dissident who was brought to trial by John Winthrop (l. c. 1588-1649 CE) and the other magistrates of the Massachusetts Bay Colony in 1637 CE for spreading "erroneous opinions" regarding religious belief and practice. She is known as the central figure in the Antinomian Controversy.

The Antinomian Controversy (antinomian from the Greek for “against the law”) challenged the authority of the colony's magistrates and, even though Hutchinson defended herself through references to the Bible and her own reputation for piety, she was convicted of spreading false beliefs and banished.

The Bay Colony had been established by Winthrop on the precept of complete conformity to Puritan theology in order to honor the covenant the colonists had made with God by which they would do his will and he would reward them with the blessings of success.

The dissident Roger Williams (l. 1603-1683 CE) had been banished in 1636 CE, and the preacher John Wheelwright (l. c. 1592-1679 CE, Hutchinson's brother-in-law) was expelled in 1637 CE for a sermon he gave advocating the primacy of God's Grace over humanity's works in attaining salvation (the central argument of the Antinomian Controversy). Both of these men, and Hutchinson, preached in accordance with the vision of the reformer John Calvin (l. 1509-1564 CE) whose views informed the Puritanism of Massachusetts Bay Colony as well as Puritanism generally but their emphasis on grace over works upset the status quo.

Winthrop, while recognizing the supremacy of grace, believed that one established one's self as a Christian through one's works. Faith, without works, Winthrop argued, was without merit, a view he supported from the biblical Book of James. Williams and Wheelwright were banished for refusing to conform to Winthrop's interpretation of Puritan theology, and Hutchinson was as well, but, in her case, three separate charges were brought:

- She was a woman exerting authority over men.

- She preached a doctrine of free grace and denied the significance of works.

- She claimed to be able to identify who was 'saved' (the elect) and who was not.

Hutchinson was found guilty on all three charges and banished from the colony in 1638 CE following her second, ecclesiastical, trial. She left, along with around 60 of her followers, and established a new colony called Portsmouth near Roger Williams' Providence Colony in modern-day Rhode Island.

She later left Portsmouth, when it was rumored that Massachusetts Bay Colony was going to absorb the Rhode Island colonies, and moved to New Netherlands (modern-day New York State) where she died in an attack by Native Americans on the settlement in 1643 CE. She is remembered in the present day as an advocate for religious freedom and tolerance as well as a proto-feminist who would not be silenced by the patriarchy.

The City Upon a Hill & Dissent

Two of Calvin's fundamental concepts, which informed Puritanism, were predestination and the elect. Based on biblical passages including Jeremiah 1:5 ("Before I formed thee in the belly, I knew thee; and before thou camest forth out of the womb, I sanctified thee…") and Psalm 139:16 ("Your eyes saw my substance, being yet unformed. And in Your book it was written of me, the days fashioned for me, when as yet there were none of them"), Calvin maintained that God had predestined some people for salvation (the elect) and others for damnation and there was nothing an individual could do to change this.

Followers of Calvin (Calvinists) became known as Puritans for their efforts in trying to 'purify' the Anglican Church of Catholic beliefs and practices. The Anglican Church was headed by the English monarch, however, and so any criticism of the Church was considered treason. The monarchy decreed civil authorities to act in church interests and so Puritans were persecuted, jailed, fined, and even executed, leading a number of congregations to flee England for the Netherlands and, eventually, to establish colonies in New England, North America.

John Winthrop led a group of 700 Puritan colonists to establish Massachusetts Bay Colony in 1630 CE and made the vision of the colony clear to them in his sermon A Model of Christian Charity, in which he wrote "For we must consider that we shall be as a city upon a hill, the eyes of all people are upon us" in that they would be a model Christian community whose success would glorify God but whose failure would bring not only God's wrath but the scorn and contempt of the world for Christianity. The colonists had formed a covenant with God, Winthrop told them, and this could only be kept if they all believed, worked, and behaved as one; dissent would not be tolerated as it jeopardized the covenant by threatening unity.

Hutchinson's Rise to Power

Anne Hutchinson arrived in Boston in 1634 CE following her Puritan pastor John Cotton (l. 1585-1652 CE) who had left England to avoid persecution. In England, Cotton and Wheelwright encouraged Hutchinson to hold meetings known as conventicles in her home with other women to discuss scripture. When she first arrived at Boston, she refrained from attending the conventicles already established in order to keep from undermining other women's authority but, when she found people were criticizing her as being too proud to attend conventicles, began to hold her own.

At first, these were little more than Bible studies, but Hutchinson was the daughter of a Puritan preacher who knew the Bible well and had been raised by her father to speak her mind freely and without fear. She began to critique the sermons of the ministers of Massachusetts Bay, pointing out where they erred through reference to the scripture and, further, took the main chair in her house in order to deliver her lectures, an honor reserved for the man of the house. She claimed that Cotton and Wheelwright were the only sanctified pastors in the colony and the rest were not even of the elect and said she knew this through spiritual gifts God had given her which allowed her to tell which people God had chosen as his own and which were to be cast into hell.

Most of the Bay Colony's ministers, she said, were clearly not of God because they emphasized the importance of a person's deeds (going to church, giving alms, performing virtuous acts, refraining from 'bad' deeds) instead of recognizing the primacy of God's free grace which pardoned sinners and welcomed them to heaven. She supported her claims through reference to scripture such as Ephesians 2:8-9 ("For by grace are you saved through faith; and that not of yourselves: it is the gift of God, not of works, lest any man should boast") and criticized any ministers who disagreed with her as being unbiblical and not of God.

Since many of these ministers were magistrates who maintained the rigidity of law and handed down often severe punishments, Hutchinson's challenge to their authority was welcomed by many. Her conventicles became increasingly popular with both men and women eventually attending, and by 1636 CE, she was one of the most popular citizens of the colony who could even claim the new governor, Sir Henry Vane (l. 1613-1662 CE) as one of the attendees at her gatherings. Winthrop and the other magistrates recognized her as a threat to the colony's unity and their own authority and held a private meeting with her and Cotton in December of 1636 CE to discuss the situation, which resolved nothing, and held her first civil trial in November of 1637 CE.

Hutchinson's Civil Trial

Hutchinson was forced to appear before the court and stand in the dock to answer the charges against her. The minutes of the trial were taken by a number of different participants. In the following exchange, the Court is understood as Winthrop who presided over the hearings.

Court: Mistress Hutchinson. You are called hither as one of those who have had a great share in the causes of our public disturbances, partly by those erroneous opinions which you have broached and divulged amongst us, and maintaining them, partly by countenancing and encouraging such as have sowed seditions amongst us, partly by casting reproach upon the faithful ministers of this country, and upon their ministry, and against them, in the hearts of their people, and partly by maintaining weekly and public meetings in your house, to the offence of all the same, since such meetings were clearly condemned in the late general assembly.

Now, the end of your sending for, is, that either upon sight of your errors, and other offences, you may be brought to acknowledge, and reform the same, or otherwise that we may take such course with you as you may trouble us no further.

Hutchinson: I am called here to answer to such things as are laid to my charge, name one of them.

Court: Have you countenanced, or will you justify, those seditious practices which have been censured here in this Court?

Hutchinson: Do you ask me upon point of conscience?

Court: No, your conscience you may keep to yourself, but if in this cause you shall countenance and encourage those that thus transgress the law, you must be called in question for it, and that is not for your conscience, but for your practice.

Hutchinson: What law have they transgressed? The law of God?

Court: Yes, the Fifth Commandment, which commands us to honor father and mother, which includes all in authority, but these seditious practices of theirs [religious dissenters] have cast reproach and dishonor upon the fathers of the commonwealth.

Hutchinson: Do I entertain, or maintain them in their actions, wherein they stand against anything that God hath appointed?

Court: Yes, you have justified Mr. Wheelwright his sermon, for which you know he was convicted of sedition, and you have likewise countenanced and encouraged those that had their hands to the petition [which supported him].

Hutchinson: I deny it, I am to obey you only in the Lord.

Court: You cannot deny but you had your hand in the petition.

Hutchinson: Put case, I do fear the lord, and my parent do not; may not I entertain one that fears the Lord, because my father will not let me? I may put honor upon him as a child of God.

Court: That is nothing to the purpose, but we cannot stand to dispute causes with you now, what say you to your weekly public meetings? Can you show warrant for them?

Hutchinson: I will show you how I took it up: there were such meetings in use before I came, and because I went to none of them, this was the special reason of my taking up this course, we began it but with five or six, and though it grew to more in future time, yet being tolerated at the first, I knew not why it might not continue.

Court: There were private meetings, indeed, and are still in many places, of some few neighbors, but not so public and frequent as yours, and are of use for increase of love, and mutual edification, but yours are of another nature, if they had been such as yours they had been evil, and therefore no good warrant to justify yours; but answer by what authority, or rule, you uphold them.

Hutchinson: By Titus 2:3-4 ["The aged women likewise, that they be in behavior as becometh holiness, not false accusers, not given to much wine, teachers of good things; That they may teach the young women to be sober, to love their husbands, to love their children"] where the elder women are to teach the younger.

Court: So we allow you to do, as the Apostle there means, privately, and upon occasion, but that gives no warrant of such set meetings for that purpose; and besides, you take upon you to teach many that are elder than yourself, neither do you teach them that which the Apostle commands, to keep at home.

Hutchinson: Will you please to give me a rule against it, and I will yield?

Court: You must have a rule for it, or else you cannot do it in faith, yet you have a plain rule against it: I permit not a woman to teach [I Timothy 2:12]

Hutchinson: That is meant of teaching men.

Court: If a man in distress of conscience or other temptation, should come and ask your counsel in private, might you not teach him?

Hutchinson: Yes.

Court: Then it is clear, that it is not meant of teaching men, but of teaching in public.

Hutchinson: It is said, [Acts 2:17] "I will pour my Spirit upon your daughters and they shall prophecy". If God give me a gift of prophecy, I may use it.

Court: First, the Apostle applies that prophecy unto those extraordinary times, and the gifts of miracles and tongues were common to many as well as the gift of prophecy. Secondly, in teaching your children, you exercise your gift of prophecy, and that within your calling.

Hutchinson: I teach not in a public congregation. The men of Berea are commended for examining Paul's doctrine; we do no more but read the notes of our teacher's sermons and then reason of them by searching the Scriptures.

Court: You are gone from the nature of your meeting, to the kind of exercise, we will follow you in this, and show you your offense in them, for you do not as the Bereans search the Scriptures for their confirming in the truths delivered, but you open your teacher's points and declare his meaning, and correct wherein you think he hath failed, and by this means you abase the honor and authority of the public ministry and advance your own gifts, as if he could not deliver his matter so clearly to the hearer's capacity as yourself.

Hutchinson: Prove that, that anybody doth that.

Court: Yes, you are the woman of most note and of best abilities, and if some other take upon them the like, it is by your teaching and example, but you show not in all this, by what authority you take upon you to be such a public instructor…

Hutchinson: I have given you two places of Scripture.

Court: But neither of them will suit your practice.

Hutchinson: Must I show my name written therein?

Court: You must show that which must be equivalent, seeing your ministry is public, you would have them receive your instruction, as coming from such an ordinance.

Hutchinson: They must not take it as it comes from me, but as it comes from the Lord Jesus Christ. (Hall, 216-219)

Hutchinson was found guilty on all charges and sentenced to house arrest until spring of 1638 CE. The minutes of the trial conclude with the passage:

Court: The Court saw now an inevitable necessity to rid her away, except we would be guilty, not only of our own ruin, but also of the gospel, so in the end the sentence of banishment was pronounced against her and she was committed to the Marshall till the Court should dispose of her. (Hall, 224-225)

John Cotton, whose views Hutchinson had fully embraced and advocated for, initially tried to defend her but, at the March 1638 CE trial, abandoned her and sided with the other magistrates. Henry Vane had left for England and been replaced as governor by Winthrop, and Wheelwright, as noted, had already been banished, as had Williams. Hutchinson, therefore, had no advocate and could do nothing but accept the sentence of banishment.

Conclusion

There was nothing in Hutchinson's meetings or beliefs which challenged the fundamental tenets of Puritan belief. It was understood by every magistrate who presided over the trial that God's Grace was freely given to the elect and no one's works could endear one any closer to God than one already was. Winthrop's concern was that Hutchinson's preaching against the significance of works and her critique of various ministers threatened the colony's unity. Her followers had already begun walking out of services presided over by ministers she claimed were not sanctified and some refused to attend these services at all.

The verdict had almost certainly been reached before the trial was even convened and Hutchinson's testimony in her own defense (she was not allowed legal counsel) was only a formality. Winthrop succeeded in maintaining the unity of his "city upon a hill" by silencing any dissenters, and later, when word reached the colony that Hutchinson and her family had been killed in a Native American raid, he rejoiced that this "American Jezebel" (as he called her) had met the end she deserved for defying God's elect and presuming, as a woman, to exert authority over men, contrary to God's dictates.

To many outside of Massachusetts Bay Colony, however, Hutchinson was an advocate for religious freedom who made a courageous stand for her beliefs against the tyranny of the Boston magistrates. The colony she established at Portsmouth continued her vision as did Wheelwright's colony in New Hampshire and Williams' Providence Colony, among many others. In the present day, this same opinion of Hutchinson still holds, and she is often referred to as a "founding mother" of the precepts which inform the cultural values of the United States of America.