Clothes in the Elizabethan era (1558-1603 CE) became much more colourful, elaborate, and flamboyant than in previous periods. With Elizabeth I of England (r. 1558-1603 CE) herself being a dedicated follower of fashion, so, too, her court and nobles followed suit. Clothing was an important indicator of status so that those who could afford it were careful to wear the correct colours, materials, and latest fashions from Continental Europe. Heavy brocade, stockings, tight-fitting doublets, long billowing dresses embellished with pearls and jewels, knee-length trousers, stiff linen collars or ruffs, and feathered hats were all staple elements of the wardrobes of the well off. The commoners, meanwhile, attempted to follow the new designs as best they could using cheaper materials, but those who tried to dress beyond their station had to beware the authorities did not fine them and confiscate the offending item.

The Historical Record

Reconstructing what exactly people wore and when has its problems. Cloth, of course, is not a very good survivor at the best of times. There are a few rare surviving examples such as a woollen shirt and breeches set belonging to a man who died after falling into a peat bog on the Isle of Shetland. However, these are few and far between. In addition to the ravages of time, the Elizabethans typically repaired and then cut and reused their clothes to get the longest life from them. The shabbiest clothes would then have been used as rags. Consequently, our knowledge of Elizabethan fashion often comes from secondhand sources such as written descriptions, sumptuary laws, and representations in art.

The Cloth Trade

The increasing population of England in the 16th century CE stimulated a corresponding growth in the cloth and clothing industries. Wool was the main material and there were four sheep for every person in England in the 1550s CE. At the same time, an increased contact with northern Europe saw new ideas and fashions spread, creating a demand for brighter colours and lighter materials. Unworked and undyed cloth was England's most important export, especially to Antwerp. However, inflation and disruptions to international trade caused by the Anglo-Spanish war led to a decline in the second half of the 16th century CE.

The manufacture of clothing for the domestic market became more sophisticated with a greater use of small machines to help in some stages of the process. These included the Dutch loom and stocking-frame knitting machine. The once staple wool, felt, and worsted clothing was now supplemented with lighter fabrics - especially cotton, linen, fustian (cotton and linen), and sometimes silk - while even the traditional materials became finer in quality and texture. Yarnspinners, weavers and dyers all worked independently and usually in their own homes. There were, as yet, no factories, even if workers were semi-professionals and many diverse households might produce for a single large-scale dealer, known as a clothier.

The Welsh borders, Gloucestershire, Wiltshire and Hampshire had long-enjoyed a reputation as the best places for English cloth manufacture. As the Elizabethan period wore on, regions like East Anglia and Kent saw the arrival of immigrants (especially Dutch and Italians) with cloth-manufacturing skills, which greatly increased the quality of local production. Hybrid fabrics lighter than the traditional English ones were produced which created new demand and, because they wore out quicker, increased sales in the longterm. The new varieties of cloth or 'new draperies' went under many names such as bays, says, serges, perpetuanas, shaloons, and grosgraines.

The Aristocracy

Men's Clothes

For men, linen underclothes (shirt and long shorts) were often embroidered and given lace decoration. Outer clothing was made of all the materials mentioned above. Additional options worn only by the aristocracy because of their expense included velvet, damask (an elaborately woven fabric of diverse material), and silk. Trousers were knee-length ('Venetian breeches') or thigh-length (trunkhose), and were often billowed out over the upper thighs and hips; later versions had pockets. Trousers often featured a codpiece which was a padded covering of the crotch. Sometimes of impressive proportions (but less so than during Henry VIII of England's reign, 1509-1547 CE), the codpiece could be unbuttoned or untied separately from the trousers when required. By the end of the century, they were replaced by the button or tied fly.

The most common upper garment for men was the doublet, a short, stiff, tight-fitting jacket which was made of wool, leather, or thick fabric. Just as today, minor changes became a sign of fashion such as the lower hem of the doublet, which started off straight but then developed into a deep V-form pointing downwards at the front. A curiosity of some doublets was the peascod - extra padding over the abdomen to imitate armour but which ended up making the wearer look as if he was strutting like a peacock. Such padding, known as 'bombast', consisted of wool, cotton or horsehair and was used in other areas to create fashionable shapes to outer clothing. Detachable collars and cuffs were highly fashionable too and were made from stiffened linen or lace. As the century wore on the ruffs became ever-more outlandish and required wire supports.

The doublet might have sleeves which could be detachable and it was closed using hooks, laces, or buttons. The shoulders could have wings and decorative tabs hanging at the waist known as 'pickadills'. On top of a doublet in colder weather, a man might wear a jerkin waistcoat and on top of that a coat which could be of any length, cut, and material. Cloaks and semi-circular capes were also worn. Trousers and upper garments were often slashed vertically in places so that underclothing or a lighter lining material could bulge through the gaps in a decorative way.

Leather was popular for some outer garments, belts, gloves, hats, and shoes. Leather was sometimes made more decorative by tooling it. Shoes for men were typically square-toed and without a noticeable heel. Earlier types of footwear were slip-on, but laces and buckles came into fashion by the end of Elizabeth's reign. Courtiers often wore fancy slipper-like shoes made from silk or velvet. Leather boots were worn when riding.

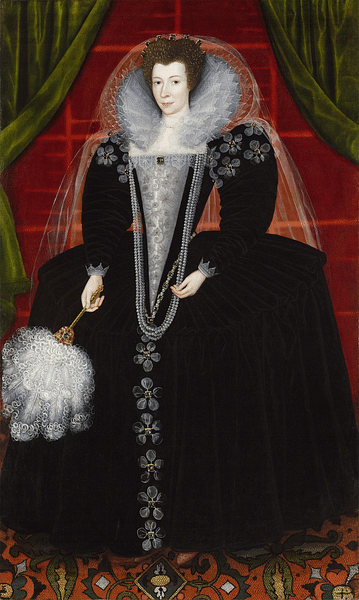

Colours often contrasted in the same outfit. All colours came from natural dyes and so the most common for the aristocracy were red, blue, yellow, green, grey, and brown. As natural dyes tend to fade relatively quickly (although outer clothes were rarely washed at all but were only brushed), wearing the brightest colours clearly showed one had the newest of clothes. Some dyes were expensive to produce such as scarlet and black and so these were another indication of wealth and status. Buttons, typically small in size but large in number, were a similar badge of wealth with the cheapest using wood, bone or horn and the more dazzling made using gold, silver, or pewter. Similarly, instead of buttons a garment might be closed or joined to another by tying a ribbon through matching holes. These ribbons were known as 'points' and the ends could be decorated with pieces of metal. In the absence of pockets, both men and women wore belts or girdles from which were suspended purses, daggers, and rapiers for men, and mirrors, grooming kits, and fans for women.

Aristocratic women often wore long dresses which had not changed very much since the Middle Ages. The kirtle dress was fitted and very long so that the feet of the wearer were almost hidden. On top of this other garments were worn. Skirts were free-flowing early in Elizabeth's reign, but there then developed a fashion for rigid skirts in the shape of a bell or cylinder. These forms were created by a series of hoops inside the material or in an undergarment. This latter construction was known as a wheeled farthingale and it had a padded roll around the waistline to push the exterior garment outwards so that the material of the dress then fell perpendicular.

An alternative to the kirtle was wearing a series of light skirts (petticoats) combined with a bodice which was usually a stiff garment made from wool and which emphasised a narrow waistline. Bodices gave support to or even constricted the upper body. They were given rigidity by inserting thin pieces of whalebone, wood or metal. Finer bodices were closed using buttons or hooks. Sometimes a reinforcing piece of wood called a 'busk' was inserted at the front of the bodice and held in position using a ribbon in the centre of the chest (which survives to this day in some undergarments). The bodice could be fastened at the front, side or back. As with the hemlines of men's waistcoats, the neckline of women's bodices varied in cut. In the mid-16th century CE, the cut was low, then rose over time and finally became low-cut again by the end of the century. Aristocratic women wore sleeves to their bodice if it were worn as an outer garment.

A third alternative was to wear a gown which was essentially a skirt and bodice attached together and worn over undergarments. These were the most extravagant of the Elizabethan garments and were typically worn with false sleeves and decorated with pearls, jewels and gold brocade.

The Commoners

Commoners wore similar clothes to the aristocracy but made along much simpler lines and with cheaper materials. Workers obviously did not wear restrictive clothing when doing their daily tasks. Materials such as cheaper linen, linen canvas, hemp canvas, and lockram (from coarse hemp) were all used for everyday working clothes that needed to be durable to wear and weather. For this reason, hems were sometimes made of more durable material so that they could take the extra wear and tear and be easily replaced if necessary to give the garment a longer life. Aprons of thick fabric or leather were worn to protect clothes, too. For a special outfit, an affordable luxury was satin (about ten times cheaper than damask). As some dyes were expensive, grey and brown shades were the most common colours in the clothing of the poorer classes.

Travelling salesmen and local mercers would have sold simple clothes like stockings and underclothes. For more elaborate outerwear, a specialised tailor or seamstress would have made the clothes on demand. Hose or loose-fitting stockings remained popular with men, although fashionable aristocrats would have preferred trunkhose. Shorter stockings tied with a garter and ribbon at the knee were popular with all classes. Lower class women sometimes wore sleeveless bodices and fastened them using laces, something upper-class women did not do. A wool or linen cap or flat hat was commonly worn, even indoors. Hats for the rich were sometimes made with fur (especially beaver) while commoners might use straw, felt, or leather. Shoes were as mentioned above but workers sometimes wore ankle-boots made of leather.

Silk, ribbons, and lace were luxury items but could be easily added in moderation to even plain clothes to make them more attractive. This was especially so as the English followed the fashion trends set by the French and Italians whose upper classes favoured more ostentatious clothing. The trend for elaborate decoration then trickled down to all classes.

Controlling Fashion

Elizabeth was the last monarch to impose sumptuary laws (notably in 1559 and 1597 CE) to curb extravagant spending on clothing and ensure the elite remained the only ones with the finest clothes. There was genuine concern that young men, in particular, outspent their inheritances in trying to keep up with the fashions set by the richer members of society. Consequently, there were strict rules on who could wear certain types of clothes, certain materials, and certain colours. There were other reasons to limit dress such as the religious views of Protestantism that called for more austere clothing, and the fact that finer and more dazzling clothes typically came from abroad and so hurt the sales of plainer home production.

Examples of restrictions included only earls or higher ranks being able to wear gold cloth. Only royalty could wear purple and only peers and their relations could wear wool garments made abroad. Servants of anyone lower than a gentleman could not wear fur of any kind, and commoners were banned from wearing stockings made from material costing more than a certain price per yard. Anyone caught breaking these sumptuary laws risked various degrees of fines and having the article of clothing confiscated. The fact that such fines were in place illustrates, though, that many Elizabethans of all classes were willing to pay any price to wear the finest fashions of the day.