The mythology of any civilization reflects its core values, greatest fears, and highest hopes and so it is with the mythology of ancient Persia. The great heroes like Karsasp, Thraetaona, and Rustum express particularly Persian values but, as with all mythical figures, are recognizable to people of any culture as role models whose best qualities are worth emulating.

This is also true for many creatures of ancient Persian mythology, the forces for good as well as evil, in that they touch upon universal concerns of the human condition through the specific details of their characters symbolizing various apprehensions and possibilities.

The stories which form the basis of Persian mythology come from early Persian religious belief. One refers to these – and similar stories from any culture – as “mythology” in the present day only because the theological paradigm has changed and a universe of many gods, spirits, angels, and demons has been replaced either by the monotheistic or atheistic model. In their time, however, they would have served the same basic purpose as the scripture of any religion does in modern times: to teach important spiritual and cultural values and assure people of order and meaning in the face of an often chaotic and frightening world.

The stories were passed down orally over the centuries until they were written down as part of the religious tradition of Zoroastrianism in the Avesta (Zoroastrian scripture) during the Sassanian Period (224-651 CE) in the reigns of the kings Shapur II (309-379 CE) and Kosrau I (531-579 CE) and then were fully addressed by the Persian poet Abolqasem Ferdowsi (l. 940-1020 CE) in his epic work Shahnameh (“The Book of Kings”) written between 977-1010 CE. By the time Ferdowsi was writing, monotheism in the form of Islam had replaced the ancient Persian religion, but his work still resonated with an audience and continues to do so.

Ancient Persian Religion

The central vision of ancient Persian religion was of a universal struggle between the forces of good and evil, order and chaos. This exact theme is the foundation of virtually every ancient world religion to one degree or another, but for the Persians, it amounted to the meaning of existence. There were two forces at work in the universe which were antithetical to each other and whichever side one aligned one's self with would define one's earthly journey and destination in the afterlife.

On the side of good was a pantheon of gods and spirits presided over by the supreme deity Ahura Mazda, the creator of all things seen and unseen, and, opposing these, was Angra Mainyu (also given as Ahriman), the spirit of evil, chaos, and confusion with his legion of demons and assorted supernatural (and natural) creatures and animals. Ahura Mazda had created human beings with free will to choose which course they would follow and, if one chose rightly, one would live well and find paradise in the afterlife, if poorly, one lived a life of confusion and strife and was dropped into the torment of hell after death.

The creatures which appear in Persian mythology almost all fall into one of these two camps except for the Jinn (also given as Djinn and better known as Genies) and the Peri (faeries) who defy easy definition as their roles seem more neutral and their actions dependent on circumstance rather than loyalty to a given cause. Although there are many different mythological creatures in the Persian tales, twelve are representative of the thematic whole:

- Gavaevodata

- Simurgh

- Huma Bird

- Chamrosh and Kamak

- Al (also given as Hal)

- Manticore

- Peri

- Suroosh and Daena

- Jinn (Djinn)

- Azhi Dahaka (Azhdaha)

All of these entities influenced human daily life to one degree or another. Some, like the Peri or the Al, were considered a constant in one's life while others – such as Simurgh or Azhi Dahaka – represented a universal paradigm which informed one's present. Whether one or the other, the natural and supernatural forces the figures represent were recognized as quite real and steps were taken to defend against the malevolent and give proper respect to those who wished only the best for humanity.

Among the latter were dogs who personified the protective aspects of divinity and figure in the representations of some of the most important benevolent creatures. Dogs warded off evil spirits, comforted and guided, and watched over one's most valuable possessions. They were considered so important that their role as guardians was preserved once the early religion of the Persians was reimagined by the prophet Zoroaster (c. 1500-1000 BCE) who kept them as the keepers of the Chinvat Bridge, the span across the abyss between the world of the living and the dead. Like all other animals, the dog owed its existence to the life-giving energies of one of the first of Ahura Mazda's creations, the Primordial Bull.

Gavaevodata

Gavaevodata is the Primordial Bull (also known as the Uniquely Created Bull, Primordial Bovine, Primordial Ox) who was among the earliest creations of Ahura Mazda. The Supreme Deity first created sky – an orb – and then filled it with water and separated the water with earth, which was planted with various types of vegetation, and then made the Primordial Bull, which was brilliant white and glowed like the moon. Gavaevodata was so beautiful, it attracted the attention of Angra Mainyu who killed it and, afterwards, it was transported to the moon and purified; from its purified seed came all animals who would feed on, and fertilize, the earth's vegetation. Once animals were created, Ahura Mazda then created human beings and then fire, but Gavaevodata was the first unique entity on earth and establishes the high value the Persians placed on animals.

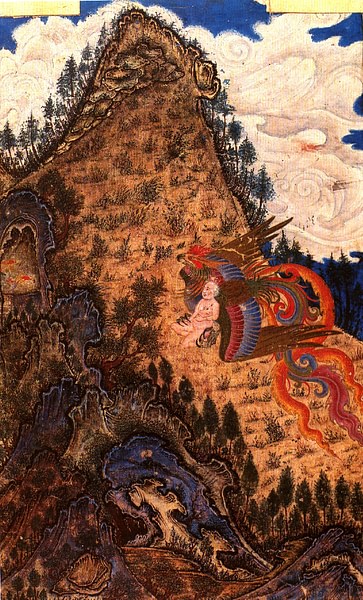

Simurgh

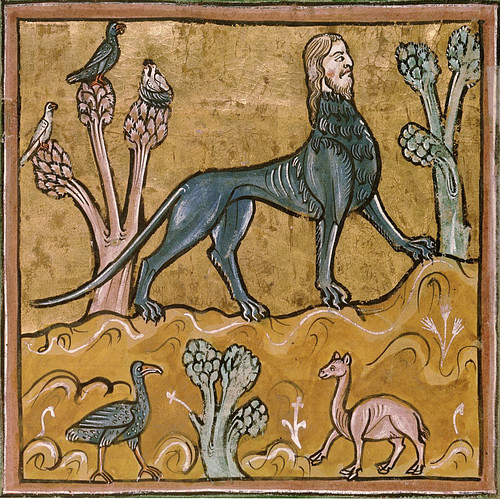

Simurgh – known as the dog-bird – was an enormous winged creature with the head of a dog, body of a peacock, and claws of a lion, sometimes also imagined with a human face. Simurgh lived high in the Alburz Mountains, existing for a span of 1,700 years before it dove into a fire of its own creation and died, only to rise again (like the later Phoenix). Simurgh was thought to possess great wisdom and features prominently in the story of the hero Zal – whom she raised – and the birth of his son Rustum (also given as Rostom and Rustam), the greatest Persian hero. She taught Zal how to deliver a difficult birth through the Caesarian section and also instructed him in medicinal herbs for healing. In early myths, she is known as Saena, the Great Falcon, who sits in the upper branches of the Tree of All Seeds and, by fluttering her wings, sends seeds flying to the ground and across the world to find their way into the earth.

Huma Bird

The Huma Bird is a later version of Simurgh, who was said to fly eternally over the earth, never landing, and if its shadow should fall upon an individual, that person would be blessed and happy all the days of their lives. The Huma was responsible for legitimizing kingship and its image was prominent at Persepolis, the magnificent ritual capital of the Achaemenid Persian Empire begun by Darius I (the Great, r. 522-486 BCE). The Huma was considered the most sacred bird and injuring – or even attempting to injure it – brought great misfortune. If someone saw or even thought they saw the bird flying overhead, however, it was a great blessing. In time, the Huma would come to symbolize the concept of elevation and enlightenment. Like Simurgh and the later Phoenix, the Huma was thought to live an immensely long life, die in its own flames, and give birth to itself afterwards.

Chamrosh & Kamak

Chamrosh and Kamak are also giant birds; Chamrosh a force for good and Kamak for evil. Chamrosh has a dog's body with the head and wings of an eagle. It lives beneath the Tree of All Seeds, gathers up those which fall when Saena-Simurgh flaps her wings, and scatters them into the wind and rain clouds which deposit the seeds all over the earth. Chamrosh is also a protective entity who defends Persians against outside invaders, especially raiders, swooping down upon them and carrying them off. Kamak plays precisely the opposite role, feeding on Persians and their livestock and bringing destruction. Kamak is so enormous that its spread wings blocked the rain, bringing drought to the land, and in the chaos which followed it easily plucked up human and animal prey to feed on. The Persian hero Karsasp finally kills Kamak by showering it with arrows continuously.

Al

The Al is a nocturnal predator who preys on newborns and was among the most feared of all the evil spirits. It was usually depicted as an old woman with sharp teeth, long, stringy hair, and talons which could also harm or kill pregnant women and would strike when mother and child were sleeping. The Al was part of a larger group of evil demons known as the Umm Naush – nocturnal predators – who were themselves a subgroup of the larger assortment of demons known as khrafstra – harmful spirits or demons – who disrupted and destroyed lives. The Al, like the other khrafstra, were invisible unless they wanted to be seen so, for the most part, only their effects made people aware of their existence. The general khrafstra manifested themselves frequently in the natural world, taking on the form of wasps, stinging ants, beasts of prey, rodents, spiders, and similar creatures.

Manticore

The Manticore (“man-eater”) is a fearsome beast with the head of a man, body of a lion, and tail of a scorpion (or, alternately, a tail ending in venomous quills which it shot at prey). It was considered invincible since its hide was so thick that no weapon could penetrate it and it moved faster than any other living thing on earth. The manticore could kill anything except for elephants and especially enjoyed human beings, devouring them whole and leaving no trace except, sometimes, stray spatters of blood. It lurked in the long, uncultivated grasses away from towns and cities and struck without warning except, sometimes, seems to have announced itself with a growl which sounded like a loud trumpet. When someone in the community went missing, and there was no clue as to what happened to them, it was judged to be the work of a manticore.

Peri

The Peris are tiny, lovely, winged creatures – neither good nor evil – who enjoy playing pranks on people but can also be helpful. They were thought to be spirits imprisoned in the fairy-form to atone for a past sin or sins but were not considered immortal and were certainly not human souls. A Peri might bring a message from the gods or, alternately, trick someone into believing some untruth or an outright lie. They largely appear in folklore as pranksters who hide objects or misdirect, and their most popular antics would be the ancient Persian equivalent of hiding a person's car keys. They were later elevated to benevolent spirits by the Muslim Arabs and served the same purpose as angels in bringing messages from the divine.

Suroosh & Daena

Suroosh is the angel who stands on the Chinvat Bridge and Daena is the Holy Maiden who works beside him. Suroosh symbolized protection and Daena one's own conscience. Both assist the newly dead in their crossing from life to death. After the soul has left the body, it was thought to linger on earth for three days while the gods came to a decision regarding one's life and final fate. The soul then approached the Chinvat Bridge which was guarded by two dogs who would welcome the justified soul and rebuff those who were evil. Daena would appear and, for the justified soul, would be a beautiful young woman while, to the condemned, she would appear as an ugly hag. Suroosh would guard the soul against demonic attack as it crossed the bridge to meet the angel Rashnu, judge of the dead, who would decide whether the soul went to the paradise of the House of Song or the hell of the House of Lies.

Jinn

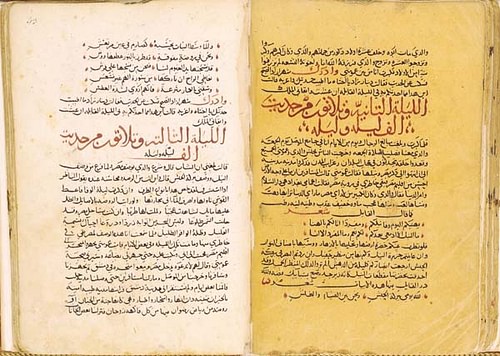

Jinn were supernatural entities who, like the Peri, were neither immortal nor human souls. They were thought to inhabit lonely places outside of towns – such as caves or hills – and had power to influence human thought and action. Like the Peri, they were neutral in the struggle between good and evil and seem to have based their actions on the circumstance of the moment. Jinn might grant a person their greatest wishes but twist the end result tragically or, at least, negatively but could just as easily honor the individual's desires in making their dreams come true. Overall, they were regarded with suspicion, and amulets were carried for protection from their influence. They are best known from the Persian work One Thousand Nights and a Night (also known as The Arabian Nights) where Jinn play a pivotal role. They were also, like the Peri, adopted by the Muslim Arabs as neutral, though potentially dangerous, supernatural forces.

Azhi Dahaka

Azhi Dahaka was the great three-headed dragon created out of the lies of Angra Mainyu to thwart any positive impulse in the world and create chaos. Dragon-serpents (azhi) frequently appear in Persian mythology as the embodiment of evil and disorder, and Azhi Dahaka was the most fearsome of them all. It is described as having a thousand senses and so is aware of any possible threat and can defend against it while, at the same time, knowing where its prey is at any time. It was considered invincible and was only finally defeated by the great Persian hero Thraetaona who captured and imprisoned him, keeping him in chains until the end of the world at which time he will be killed by the resurrected Karsasp, slayer of Kamak.

Conclusion

These figures, and many others like them, embodied the daily fears of the people such as loss of a child (the Al) or unexplained death or disappearance (the manticore) or why events in life could go so wrong when everything seemed to have been proceeding so smoothly. Alternately, entities like Suroosh and Daena or creatures like Simurgh gave people confidence that they were cared for, that there was someone looking out for them and protecting their interests.

One notable example of this is the creature not yet mentioned here known as the Karakadann/Koresk – better known as the unicorn – a shy and elusive animal who kept to itself in remote places. Its horn was thought to be a powerful antidote to poison and seeing one was thought to bring good luck. Even if one never actually saw a Koresk, one could still have hope one would someday and all one's problems would be solved in a sudden streak of supernatural good fortune.

The great heroes like Thraetaona or Karsasp or Rustum who defeated the forces of chaos served the same purpose, standing for the principles of goodness, justice, and order in an uncertain world and giving people hope that these ideals would triumph over selfishness, cruelty, and chaos. One of the central values of ancient Persian culture was storytelling, and through their rich mythology, they created some of the most memorable characters and tales in world history which have fascinated audiences ever since.