There were 18 martial arts (bugei or bujutsu) in medieval Japan, and these included use of weapons, unarmed self-defence techniques, swimming, and equestrian skills. Initially designed to hone the skills of warriors for greater success on the battlefield, many of the arts were later practised by civilians as a method to foster discipline, agility, and mental alertness. Many of the arts remain popular today, notably judo, kendo, karate, and aikido.

Origins & Developments

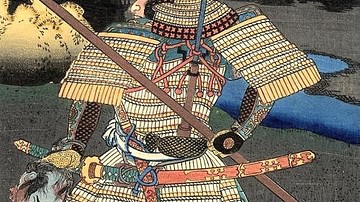

Several of the martial arts which became popular in medieval Japan were introduced from China where, according to tradition, they had begun as a way for Buddhist monks to ensure they were fit enough to sit in meditation for hours on end and as a method to aid their concentration. Over time, these exercises began to incorporate skills with weapons and they spread across to Japan. Kendo, for example, which emphasised skill with a sword, was likely introduced there in the 7th century CE. Nevertheless, the Japanese added their own weapons, skills, and psychological emphasis to martial arts to both suit their own military needs and their philosophical approach. From the 10th century CE and throughout the medieval period (1185-1603 CE), warriors, especially the samurai, practised their skills at weaponry and horse riding in order to prepare themselves for the challenges of the all-too-frequent wars that plagued the country as rival warlords fought for dominance.

It was only in the Edo period (1603-1868 CE), though, that these practice activities became formally known as the martial arts we are more familiar with today, that is, peacetime activities designed to promote not only martial skills but also discipline and a philosophical and spiritual approach to life in general. In Japan, the warrior and thunder god, Takemikazuchi-no-kami, is considered the patron of the martial arts and many training halls (dojo) still today have a small shrine dedicated to him.

The 18 Classic Martial Arts

Medieval warriors often specialised in only a few of the martial arts, and training clubs usually concentrated on certain categories such as swordsmanship, horse riding or unarmed combat. There were 18 classic martial arts in medieval Japan. Known collectively as bugei juhappan, these were:

- archery (kyudo/kyujutsu)

- barbed staff skills (mojiri)

- chained sickle throwing (kusarigamajutsu)

- dagger throwing (shurikenjutsu)

- fencing/swordsmanship (kendo/kenjutsu)

- firearms skills (teppo)

- horsemanship (bajutsu)

- needle spitting (fukumibarijutsu)

- polearm skills (naginata jutsu)

- rope skills (torite)

- short sword skills (tanto)

- spying (ninjutsu)

- staff skills (bojutsu)

- spearmanship (sojutsu)

- swimming (suieiijutsu)

- sword drawing (iaijutsu)

- truncheon skills (jitte)

- yawara (judo/jujutsu)

The Main Martial Arts

Archery

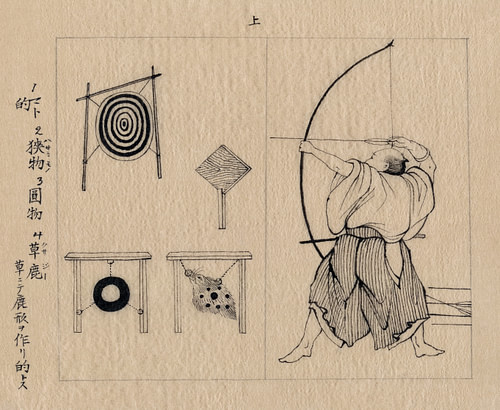

The main weapon of the samurai warriors of Japan was, for much of their early history, the longbow, and skill with this weapon was practised in the martial art of kyudo or kyujutsu ('the way of the bow'). Dating back to at least the 6th century CE, there were two distinct types of archery. The first was a formal civil event where the style and technique of a standing archer were judged as more important than hitting the target. The archer first aimed his arrow at the sky and then the earth to symbolise the unity between these two elements and then, riding on horseback, he aimed at a group of three circular targets. Each target was set around 60 metres apart and the archer had to hit one of their five concentric circles while following a circular track with his horse. The archers who had managed to hit all three targets progressed to the next round where they had to hit three much smaller clay targets. The winner of the competition was the archer who had hit closest to the centre of the targets as decided by a judge. This form of archery is known as Yabusame and, dating back to the 11th century CE, it is still popular in Japan today.

The second type of archery was the much more martially useful quick firing of bows, again aiming at targets while riding a horse. Archers also practised in mock battles and there were even some cases of real battles being settled by two mounted archers repeatedly charging at each other to settle who would be the victor.

Bows measured 1.5-2.5 metres or 5-8 ft in length and were typically made of wood and laminated bamboo, often protected by lacquer. Bamboo arrows varied in length but were usually measured in units of the clenched fist, a standard arrow being 12 fists in length, equivalent to 86-96 cm (34-38 inches). Arrows had three or four feather fletchings to increase their stability in flight. The bow was challenged by the sword as the main weapon of warriors in the medieval period but it was really the introduction of firearms in the late 16th century CE that saw its ultimate decline on the battlefield.

Spears

Another key traditional weapon in Japanese warfare was the spear (yari) and, designed not for throwing but thrusting, skill with it was practised in the art of sojutsu. Most had a wicked double-edged blade measuring 30-75 cm (12-29 inches) in length. A common type had an L-shaped blade designed to help hook an enemy rider from their horse. Likewise, the single-bladed polearm (naginata) was a staple weapon of infantry, but it did not have its own specific martial art until the 17th century CE. The latter art was one of the few practised by both men and women, the latter typically being daughters of samurai.

Swords

The sword (nihonto) has always held special significance in Japan as it was a weapon used by the gods during the Shinto creation story and is one of the three items of the ancient Japanese royal regalia. Swordsmanship was practised in kendo ('the way of the sword') which originally used real swords but these were later replaced by less-lethal weapons with bamboo blades (shinai). The traditional Japanese long curved sword (katana) was around 60 cm (2 ft) in length and had a strong steel blade with a single, super-sharp cutting edge. It was held with both hands and the martial art was designed to hone the reflexes and mental alertness which would be indispensable on the battlefield. The sword would replace the longbow and become the principal weapon of elite samurai warriors from the Kamakura period (1185-1333 CE). Drawing the sword in an efficient manner was a skill in itself (iaijutsu) and the objective in actual warfare was to cut one's opponent in a single movement using grace and speed. As with the unarmed martial arts, the emphasis of swordsmanship techniques was on defence rather than attack.

Horses

Horsemanship or bajutsu was a key skill in Japanese warfare from the 5th century CE onwards. Japanese horses, which mostly came from the wild northeast of Japan, tended to be short but sturdy. Stallions were preferred but could be temperamental and difficult to handle. Control by the rider was aided by reigns, bit, bridle, and a wooden saddle (kura) which had cup-shaped stirrups, allowing the rider to fire his bow in a standing position and making it much more difficult to unseat him. Although rarely armoured, horses' feet were shod and they even sometimes wore straw sandals (umagutsu) to reduce noise when approaching the enemy.

Swimming

Swimming or suieiijutsu became a popular martial art from the 12th century CE onwards and was not merely a matter of crossing a stretch of water as quickly as possible but doing it carrying weapons and quietly, including doing so underwater. This was, no doubt, in response to the rise in the number of castles in Japan and their staple feature of a wide protective moat.

Ninjas

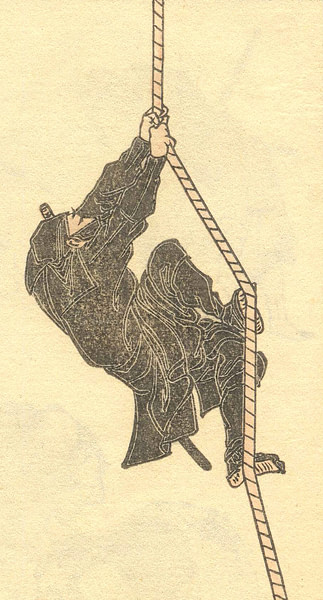

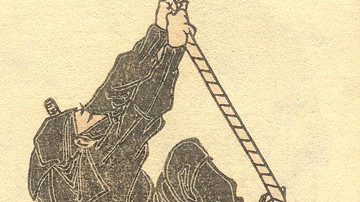

Ninjutsu was the martial art practised by ninjas, the specialised troops of Japanese armies who were charged with sabotage, assassination, espionage, and assaulting castles. Ninjutsu involved acquiring a high level of skill using all manner of weapons and equipment from grappling hooks to the famous throwing stars (shuriken). Trained by a master or sensei from childhood at a specialised school, a ninja learnt all the other classic martial arts and then progressed to such highly specialised skills as map-reading, camouflage, and jumping across rooftops as well as learning how to tie up a prisoner, mix poisons, and use explosives.

Into the Modern Era

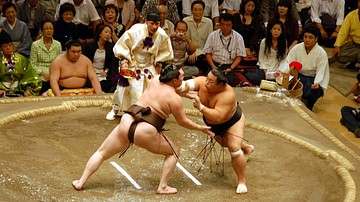

Judo ('the way of softness/gentleness') was only popular from the 19th century CE but it had evolved from jujutsu ('soft techniques') which had become popular ever since the 8th century CE in Japan. The attacks, grips, and throws developed from much earlier forms of wrestling. Essentially a method of self-defence, proponents are required to possess great agility and move in a quick and precise manner, aiming for weak points in their opponent's anatomy. Other similar late-comers to the martial repertoire were karate ('empty hand'), only popular in Japan from the 20th century CE, and aikido ('way of meeting spirit') where attackers are immobilised by applying pressure to joints, sometimes even dislocating them.

This content was made possible with generous support from the Great Britain Sasakawa Foundation.