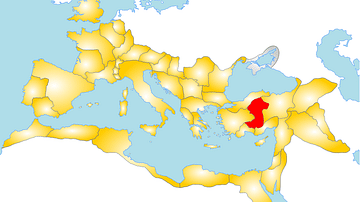

Galatia was the most long-lasting and powerful Celtic settlement outside of Europe. It was the only kingdom of note to be forged during the Celtic invasions of the Mediterranean in the 4th and 3rd centuries BCE. From its foundation, Galatia was a formidable power in Asia Minor, capable of demanding tribute from powerful states like the Kingdom of Pergamon.

Galatia was situated in eastern Phrygia, a region now within modern-day Turkey. From this stronghold, the Galatians raided and pillaged their neighbours in Asia Minor and the Aegean. This aggressive stance brought it into conflict with several Hellenistic powers, and eventually even the Roman Republic. Despite a staggering defeat in the Galatian War of 189 BCE, the Celtic communities of Galatia maintained their identity well into Late Antiquity.

The Celtic Exodus

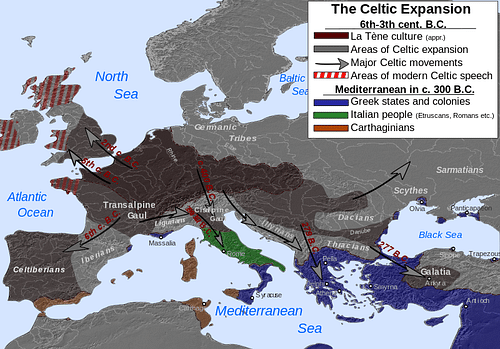

By the turn of the 5th century BCE, overpopulation had created a scarcity of resources in Europe. In response to a lack of resources and greater competition, Celtic warbands turned their sights south. In Celtic society, young leaders had to win prestige by displaying prowess as warriors and acquiring wealth through raiding in order to climb the social ladder. Established leaders were similarly pressured to maintain their prestige once they had achieved a high rank. This competitive social structure encouraged armed conflict and daring raids.

At first, small groups began raiding further and further afield, to regions like Italy and the Middle Danube. This eventually snowballed into large-scale population movements into the Mediterranean basin during the 4th and 3rd Centuries BCE. Ancient Roman authors are probably correct in surmising that migrating Celts were partly motivated by their appetite for Mediterranean luxuries like wine and olive oil.

A large coalition of Celtic tribes led by a king named Brennus invaded Greece in the 3rd century BCE. Brennus and his Celts were defeated at Delphi after a few initial victories, after which the allied tribes were scattered. However, a splinter group detached from this coalition and invaded Thrace before laying siege to Byzantium. Two chiefs, Leonorius and Lutarius, led this splinter group of three tribes, the Tolistobogii, the Tectosages, and Trocmi. Only about half of their number were fighting men, the rest were women and children. This mass of settlers relied on raiding and pillaging to support themselves but was in dire need of a secure home in the short term.

The followers of Leonorius and Lutarius were destined for something more impressive than the fate which befell the tribes led by Brennus. It was these Celts who became known to history as the Galatians after crossing into Asia Minor.

Entry Into Anatolia

Nicomedes I of Bithynia (r. 278-255 BCE) invited Leonorius and Lutarius into Anatolia as his allies in exchange for their martial assistance. Nicomedes I was at that time vying against both his brother Zipoetes II of Bithynia and the Seleucid king Antiochus I Soter (r. 281-261 BCE). The Celts proved to be valuable allies, and Nicomedes I came out victorious in his battles. This alliance allowed Leonorius and Lutarius to bring their people into a new and promising land.

When the Galatian tribes arrived, Anatolia was already teeming with different peoples, including many other transplanted communities. Greeks had long since established colonies and city-states in Asia Minor, and Thracian tribes had emigrated to the peninsula even before that. Many of the tribes and most of the cities were somewhat Hellenized, having been influenced by, and in turn influencing, Greece for centuries.

Galatia, a Celtic Kingdom in Asia Minor

For some time the Celts were able to rampage over Asia Minor without challenge. From their initial footholds in the Near East, they staged raids against the surrounding cities. This brief period of free reign was brought to an end by Antiochus I Soter at the “Elephant Battle” of 275 BCE. The Celts facing Antiochus had never before seen elephants, and the battle turned into a crushing defeat.

After the Elephant Battle, the Celtic tribes made an alliance with Mithridates I of Pontus (r. 281-266 BCE). Around 232 BCE, the Celts settled around the city of Ankara, in a part of Phrygia. The Hellenistic kings who divided Asia Minor were in agreement about the need to resolve the Celtic problem, and settling the marauding tribes in the barren hills of Central Anatolia seemed like a fitting solution. Eventually, this region became known as Galatia, deriving from Galatae, a Greek name for Celts.

The Celts who settled in Galatia brought with them their pastoral lifestyle. While some major cities like Ankara were used as tribal headquarters, the Celts built no new cities of their own and even destroyed some of those which already existed. Galatian tribes built hillforts, known as oppida (sing. oppidum), to protect their farmsteads and settlements. Tribal groups staked out their own territories, and competition between Celtic Galatian chiefs quickly resumed.

The Roman geographer Strabo (c. 64 BCE - c. 24 CE) described the history of Galatia's political organization:

The three tribes spoke the same language and differed from each other in no respect; and each was divided into four portions which were called tetrarchies, each tetrarchy having its own tetrarch, and also one judge and one military commander, both subject to the tetrarch, and two subordinate commanders. The Council of the twelve tetrarchs consisted of three hundred men, who assembled at Drynemetum, as it was called. Now the Council passed judgment upon murder cases, but the tetrarchs and the judges upon all others. Such, then, was the organisation of Galatia long ago, but in my time the power has passed to three rulers, then to two, and then to one, Deïotarus, and then to Amyntas, who succeeded him. But at the present time the Romans possess both this country and the whole of the country that became subject to Amyntas, having united them into one province.

(Geography, 12.5.1)

While Celts did not immigrate to Asia Minor in large enough numbers to displace the local populations, they did become the ruling caste. Celtic culture seems to have permeated the lower levels of society and was assimilated into local traditions.

Rivalry with the Kingdom of Pergamon

The Galatians did not sit idly by after establishing themselves in Galatia, they soon resumed their raids in the rest of Asia Minor. Galatian raids against Aegean cities intensified in the 3rd century BCE, spurred on by the vast wealth and political instability of the Hellenistic cities.

The Attalid Dynasty, based in their capital of Pergamon, was the great power in the region and the most powerful enemy of the Galatians. Eumenes I of Pergamon (r. 263-241 BCE) paid the Galatians tribute in exchange for peace, as the other rulers of Asia did. Eumenes I's successor Attalus I (r. 241-197 BCE) had no intention of appeasing the Galatians with treasure. Instead, Attalus I went to war with the Galatians to assert his power.

Attalus I eventually defeated the Galatians at the Springs of Kaikos in 233 BCE, a dramatic victory that became his crowning achievement. Pausanias (c. 110-180 BCE) recounted a Greek legend that Attalus and his defeat of the Galatians had been prophesied.

That the Celtic army would cross from Europe to Asia to destroy the cities there was prophesied by Phaennis in her oracles a generation before the invasion occurred:

'Then verily, having crossed the narrow strait of the Hellespont,

The devastating host of the Gauls shall pipe; and lawlessly

They shall ravage Asia; and much worse shall God do

To those who dwell by the shores of the sea

For a short while. For right soon the son of Cronos

Shall raise them a helper, the dear son of a bull reared by Zeus,

Who on all the Gauls shall bring a day of destruction.'

By the son of a bull she meant Attalus, king of Pergamus, who was also styled bull-horned by an oracle.

(Paus. 10.15.2-3)

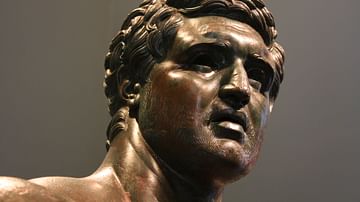

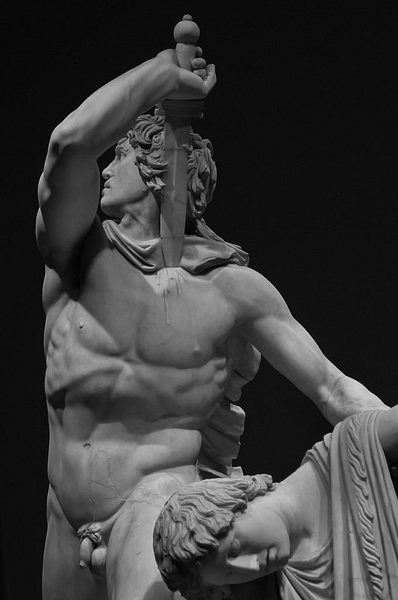

Attalus I took on the epithet 'Soter' ('the Saviour') to commemorate his defeat of barbarians who threatened the Hellenistic cities of Asia Minor. Attalus I Soter commissioned artwork depicting his defeat of the Galatians. It was around this time that the Galatian or Gallic warrior became the archetypal barbarian of the Greek imagination.

The Galatian War

In the early 2nd century BCE, Galatia was dragged into the conflicts between the Roman Republic and the Seleucid Empire. Antiochus III (223-187 BCE) employed large numbers of Galatian troops in his wars with the Kingdom of Pergamon. These Galatians were present for Antiochus III's defeat at the Battle of Magnesia in 190 BCE by a Roman-Pergamene alliance. Galatian involvement in the conflict was used by the Roman Republic as a casus belli for the Galatian War in 189 BCE. The year after the Battle of Magnesia, a Roman general named Gnaeus Manlius Vulso was tasked with conquering the kingdom of Galatia. Attalus I assisted the Romans in this war against their mutual enemies.

In preparation for war, the Tectosages gathered their forces around the city of Ankara. The Tolistobogii and the Trocmi amassed their numbers around Mount Olympus (modern Uludağ) in Galatia, not to be confused with the more famous mountain in Greece. The Roman-Pergamene alliance defeated the Galatians at Mount Olympus, effectively conquering two of the three tribes in Galatia.

It was not easy to get at the number of those killed, for the flight and the carnage extended over all the spurs and ravines of the mountain, and a great many losing their way had fallen into the deep recesses below; many, too, were killed in the woods and thickets. Claudius, who states that there were two battles on Olympus, puts the number of killed at 40,000; Valerius Antias, who is usually more given to exaggeration, says that there were not more than 10,000. The prisoners, no doubt, amounted to 40,000, because they had carried with them a multitude of both sexes and all ages, more like emigrants than men going to war.

(Livy, Roman History, 38.23)

Gnaeus Manlius Vulso followed up this victory by defeating the Tectosages at Ankara later that year, effectively bringing all of Galatia to heel. In the aftermath of the Galatian War, the Roman Republic forced the Galatians to cease all raiding in western Asia Minor. However, the Romans also prevented the Pergamon from dominating Galatia.

Propaganda & Power on the Pergamon Altar

By 167 BCE, the Galatians had once again returned to their marauding ways, and Eumenes II of Pergamon (197 - 159 BCE) was at war with them for the next two years. Like his predecessor Attalus I, Eumenes II promoted himself as a protector of the Greeks and their champion against the Galatians.

Eumenes II commissioned four monumental works to commemorate his triumphs over the Celts on the Pergamene Acropolis. These monuments paid homage the triumphs of the Attalid dynasty, including Eumenes II's defeat of the Galatians c. 166 BCE. Legendary events like the founding of Pergamon by Telephus, and the Gigantomachy from Greek mythology were the most prominently portrayed themes, but other incidents from myth and history were also portrayed.

The monuments have since been lost, but several large marble blocks from the 2.48 meter base of the monument have been excavated. An inscription from one of these blocks reads:

King Attalos having conquered in battle the Tolistobogii Gauls around the springs of the river Kaikos [set up this] thank-offering to Athena. (Pollitt, 85)

The famous 'Dying Gaul' (in the Capitoline Museums) and the 'Ludovisi Gaul' (in the Museo Nazionale di Roma) are some of a few Roman copies of 2nd-century BCE Hellenistic art that may have originally been a part of this monument.

Legacy of Galatia

Galatia emerged from a period of heavy migration as the only great kingdom born from the Celtic diaspora. The strength of its armies secured its place in the violent world of the Hellenistic Period. Galatians were widely used as mercenaries in the ancient world, and Celtic tribes from Europe continued to migrate to the Mediterranean where they found work as mercenaries.

Galatians were used by all the great Hellenistic armies and fought in the wars of the Seleucids and Ptolemies. Celtic mercenaries had a reputation of being capable but unreliable warriors. Despite their value as mercenaries, Galatians were often mistrusted for their foreign ways and their lack of loyalty to the kings who purchased their services.

The nation of the Gauls, however, was at that time so prolific, that they filled all Asia as with one swarm. The kings of the east then carried on no wars without a mercenary army of Gauls; nor, if they were driven from their thrones, did they seek protection with any other people than the Gauls. Such indeed was the terror of the Gallic name, and the unvaried good fortune of their arms, that princes thought they could neither maintain their power in security, nor recover it if lost, without the assistance of Gallic valour.

(Marcus Junianus Justinus, Epitome of the Philippic History of Pompeius Trogus, 25.2)

Galatia was heavily influenced by Asiatic, Greek, and Roman cultures in antiquity, but the region also maintained a strong Celtic tradition in the local language and the Celtic heritage of its ruling families. The most well-known reference to ancient Galatia is Saint Paul's Epistle to the Galatians in the New Testament. In the 4th century CE, Saint Jerome (347 - 420 CE) remarked upon similarities between the language of the Galatians and the Celts in Treverorum (Trier).

- Previously published as Celts in Asia Minor: Part 4 of Celtic History Explained on Magna Celtae