The chariot was the elite arm of ancient Indian armies in the Vedic (1500 BCE – 1000 BCE) and Epic periods (described by the Ramayana and the Mahabharata, 1000-600 BCE) because of the advantages it conferred and the selection of plain ground as battlefields. Chariots were highly mobile and gave an advantage over infantry and cavalry. In the course of time, beginning around the 6th century BCE, they lost their pole position to the elephants, to the extent that the chariot corps did not constitute part of the ancient Indian army anymore. However, in the early centuries of Indian warfare, they were deemed irreplaceable.

The Importance of the Chariot

In ancient India, initially the army was fourfold (chaturanga), consisting of infantry, cavalry, elephants and chariots. In the Vedic period, the chariot was given prime importance. The Mahabharata regarded the chariots as invincible instruments of battle, and the other arms were seen as insignificant. The elite warriors, including kings, princes and commanders, always fought on chariots. The elite warriors were lauded as great chariot fighters (maharathas or maharathis) and it was considered degrading for them to fight as part of any other arm of the army. The Vedic Samhita literature contains the terms rathagrtsa (skilled in chariot fight), rathaujas (mighty in chariot fight), and rathechitra (glorious in chariot), as epithets of chieftains and commanders.

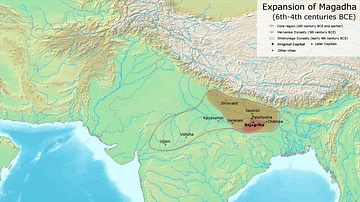

The importance of chariots lay in the fact that they had mobility and could carry soldiers who could shoot while moving through the length and breadth of the battlefield. These vehicles could easily mow down enemy infantry. The army of Magadha under King Ajatashatru (492-460 BCE) used the rathamusala (a chariot with a mace attached), which caused much havoc among the enemy army. The chariots and cavalry also had an advantage when fighting against an enemy infantry primarily using bows. Since archers are useless at close quarters, the mounted troops could thus easily approach them and cut them down. It is for these reasons that in the Vedic and Epic periods, the selection of the battlefield was made based on how best the chariots could be employed.

Organisation of the Chariot Corps

Battle chariots were known as sangramika while chariots used in assailing enemy strongholds were called parapurabhiyanika. In the Mahabharata, chariots were combined with other warriors to make up new units. A chariot and an elephant, three horses and five foot-soldiers formed a patti, which was the lowest unit. The highest unit was the akshauhini, which in theory at least, consisted of 21,870 chariots, 21,870 elephants, 65,610 horses and 109,350 infantry. In practice, it is highly likely that the numbers were a lot less as it was not possible to field such numbers by one side alone.

Under Chandragupta Maurya (321-297 BCE), the Mauryan army came to possess 8,000 chariots. Under the Mauryas (4th century BCE - 2nd century BCE), where the thirty-member war office was made up of six boards, the fifth board headed by the rathadhyaksha (superintendent of chariots), looked after the chariots. Besides military duties, he also settled accounts of provisions and the wages of employees preparing chariots and other things. He was also to keep them contented and happy by giving adequate rewards (yogyarakshanushthanam) and ascertain the distance of roads to ensure that the chariots ran smoothly. Princes were trained in chariot warfare as a part of their general military education.

Construction

The chariot or ratha was generally a two-wheeled vehicle. The kosha or box, where the warriors stood, was made of wickerwork or of leather on a light wooden framework. It was fixed on a wooden axle (aksha) fixed centrally to the chariot-floor and was fastened by straps of hide. The wheels were fixed to its ends and projected free of the vehicle's body on each side, secured by linchpins on their outer faces. There was also a tall flagstaff (dhvajayashti), carrying the warrior's ensign in the form of an image or emblem, below which was his flag (dhvaja).

A central pole projected forwards from the bottom of the chariot. Its end passing through a hole in the yoke, this pole would rise at an angle with the chariot floor, usually in a curve but sometimes also in a straight line. A stout pin (shamya) or bolt was provided through the pole against which the yoke was tied with leather straps. The yoke (yuga) was laid across the necks of the horses on either side of the pole. Two horses were usually used per chariot, but at times, three or four could also be seen. The horses were yoked abreast as this broad front could wield a greater projectile force.

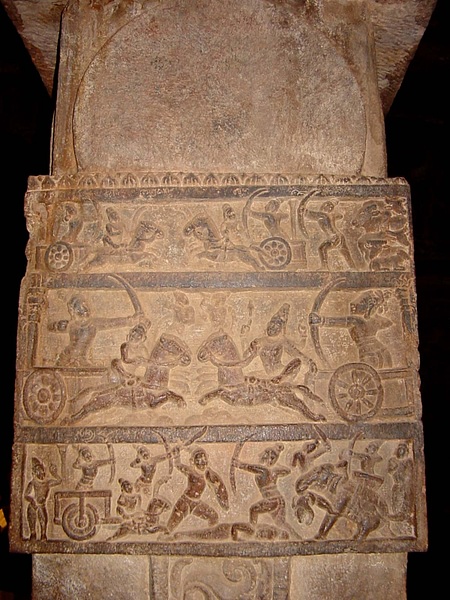

The wheels had metal tyres whose rim was called pavi, a felly (pradhi), spokes (ara) and a nave (nabhya) with a hole (kha). The rim and the felly together were called nemi. The Vedic chariot wheel seems to have had four to eight spokes. More spokes were probably added in later periods. The sculptures at Sanchi and Bharhut represent these Vedic chariots but with slight modifications found useful in their own times. Timber was mainly used as the construction material for chariots. The rathadhyaksha was tasked with overseeing the construction of chariots.

Troops & Equipment

The troops mounted on a chariot consisted mainly of armoured or unarmoured archers and missile troops efficient in hurling clubs and cudgels. It was the rathadhyaksha's job to see that they were efficient in fighting, charioteering, fighting seated on a chariot and in controlling chariot horses, besides having the necessary equipment. When dislodged from a chariot, the warriors were expected to carry on the fight on foot and hence were trained accordingly. Thus, they also carried spears, swords, daggers and shields.

Initially, the chariots carried two riders, i.e., the warrior and the chariot driver. The warrior called savyeshtha or savyashtha stood on the left, or sat on a seat called garta or vandhura. The driver or sarathi stood on the right and remained standing (sthatr). He wore a turban, an ornament (nishka), a garland (sraj), with the upper part of the body naked, and probably carried no weapons. The Buddhist Vinaya texts (500 BCE- 300 BCE) mention four riders. Two were armed foot-soldiers looking after each wheel, while the warrior and the driver occupied the chariot.

The archers used arrows tipped with metal or horn, and sometimes, even poison. Quivers containing arrows and spears were tied to the box of the chariot. In a sculpture made during the Gupta period (3rd century CE - 6th century CE) depicting a scene from the Mahabharata, the chariot warriors have quivers tied to their backs as well as on the chariot body. They are not wearing armour but only wrist-guards. A tiny figure, possibly depicting the charioteer, can be seen in the chariot on the right. The chariot horses were often protected with armour. This was either some form of chain-armour of iron or bronze washed in gold or with leather robes or even with wooden breastplates.

Chariots in Battle

Kautilya (c. 4th century BCE) in his Arthashastra provides details as to how chariots should be employed in battle. For opposing enemy chariots, 15 men or five horses should be used. As many as 15 footmen (padagopas) should be maintained for a chariot's support during battle. In the Mahabharata, they are referred to as anucharas or padanugas.

While forming for battle, three groups (anika) of three chariots each were to be stationed in front of the army with the same number on the two flanks and the two wings. The number of chariots in this array (of three groups of three chariots each) could be increased by two and two till the increased number amounted to 21. If the chariots were in surplus, two-thirds of that number could be added to the flanks and the wings, the rest being put in front.

Elephants were to be placed at the extremities of the battle array and horses and principal chariots on the flanks. The array in which elephants were at the front, chariots at the flanks and horses at the wings was believed to break the centre of the enemy's army. 'Disturbing the enemy's halt; running against; running back; and fighting from where it stands on its own ground—these are the varieties of waging war with chariots' (Shamasastry, p. 535).

In battle, the chariot warriors aimed at the flagstaff, horses and charioteers of their opponents, who were doing likewise. If the opponent was not killed, he would jump down on the ground from his damaged chariot and continue the fight on foot until he was picked up by other chariots from his own side. The chariot warriors also engaged the enemy infantry, constantly shooting at them. In the Mahabharata, duels between elite warriors are mentioned. The heroes keep shooting arrows at each other, and the duel ends with either the death or flight of one of them.

Causes for Decline

The main drawback of the chariot was that it could not be employed on hilly or difficult terrain, or in adverse weather conditions. They needed vast plain grounds to operate effectively, otherwise their mobility was constricted. In the Battle of Hydaspes (326 BCE), the chariots employed by King Porus (c. 4th century BCE) against the Macedonians led by Alexander the Great (356 – 323 BCE), failed miserably due to mud and the rain. The rain which had raged during the night before the battle made the ground slippery and unfit for the horses' movement, while the chariots kept sticking in the muddy sloughs formed by the rain. They were also bogged down by their own weight. The idea to use the momentum of the weight and speed of the horse and chariot as an offensive weapon did not succeed as the broken and slippery ground jolted the riders off from their chariots. Some horses took fright and dragged the chariots into the sloughs and pools of water, and even into the nearby river. The charge of the Macedonian cavalry made matters worse for them as the chariots were thrown into confusion and many riders were slain.

The changing nature of ancient Indian warfare led to factors such as surprise, going into battle at the last moment and fighting in varied terrain determining the battle site. In such a scenario, the effective use of the chariot corps could no longer be the deciding factor in this selection. The other branches of an army could be easily employed in different terrains and hence the chariots were passed over.

Over time, the ancient Indians realised that the elephant (its own drawbacks notwithstanding) served the purpose better. Elephants could be effectively employed in siege warfare, had much more power owing to their size, afforded a fort-like protection to the riders and were more mobile. An elephant also provided a better commanding view of the battle to the general riding it. The psychological impact of an elephant mowing down hapless infantry was also much greater than that of the chariot.

This trend of passing over the chariot had begun in about the 6th century BCE. Kings and commanders began to ride elephants. In a relief at the Sanchi stupa which shows seven kings marching to lay siege to the city of Kushinagara, only one king rides a chariot while the other six are riding elephants or horses. In another relief at the stupa which shows the Mallas defending the city against the armies of these kings, greater importance is attached to the elephants and infantry, particularly archers. This siege likely took place sometime in the fifth century BCE and thus this sculpture shows that by this time, the process of the decline of chariots as an effective military arm was already underway.

Chariots thus became insignificant and lost their elite status. This development eventually led to the chariots being phased out of the ancient Indian armies, so much so that though sculptural representations in the later periods showed chariots in battle, they more mostly scenes from the Mahabharata and had nothing to do with contemporary warfare which did not employ chariots. So even while the Mauryas maintained chariots, they were not given the same importance as other arms. The space that Kautilya gives to chariots in his book is much less when compared to elephants, and even infantry.

Legacy

The development of the chariot was largely due to the need for mobility on the ancient Indian battlefield. Though eventually elephants and later horses were seen as fulfilling this purpose better, the beginning lay with the chariot. Though they themselves became redundant and went out of commission, they left behind a legacy of the need to develop units possessing mobility and the ability to effectively tackle the numbers of the enemy mostly concentrated in the form of the infantry.