The gods of ancient Egypt were worshipped as the creators and sustainers of all life. People acknowledged their supremacy and intimacy daily through rituals, amulets, and their labor for the king. Everyone, from farmers to craftsmen to merchants, nobility, scribes, and the king, observed their own specific acts in their own ways to honor the gods but the basic structure, the understanding, of these rituals came from the priesthood.

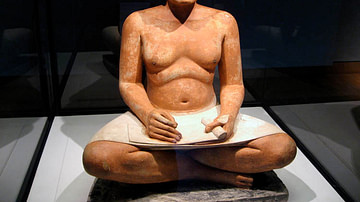

Priests in ancient Egypt were thought to have a special relationship with the gods. Their primary function was to care for the god they served. Priests did not preside over worship services, read from scripture, or proselytize; their purpose was to tend to the needs of the gods, not the people.

This is not to say they were not involved in the lives of the community, however. Their work was thought to please the gods and the gods would then show their pleasure through the inundation of the Nile River which fertilized the fields and through the abundant harvest which resulted. Health and prosperity were signs that the gods were content with the sacrifices and offerings made to them and, conversely, sickness and famine and poverty were clear indications something had gone wrong.

When times were good for the Egyptians, the gods were praised and offerings made by the priests in thanks; when life was difficult the priests were expected to determine what had gone wrong and mend the relationship between the people and their gods. Egyptologist Margaret Bunson comments on this:

From the earliest eras, the spiritual aspirations of the Egyptian people were given expression by the priests, who maintained their cults and generally performed their religious obligations with loyalty and scrupulous dedication. (209)

The Power of the Priests

The king was considered the First Priest since he was the mediator between the gods and the people and it was the king's office which would appoint the high priest to a temple. Obviously, however, the king had many other duties and so the high priest oversaw the obligations due the gods and also the day-to-day operations and staff of the temple complex.

Among the most important duties of these priests were mortuary rituals performed for the continued existence of the soul in the afterlife. Everyday, after the morning rituals of Lighting the Fire and Drawing the Bolt (encouraging the sun to rise by lighting the temple fire and opening the shrine of the god) priests would occupy themselves with prayers and offerings to the souls of the dead, especially prior kings, queens, and nobles.

During the Old Kingdom (c. 2613-2181 BCE) the kings built their now-famous mortuary site at Giza and developed others elsewhere. All of these sites required priests to perform the same rituals they did at the temples to ensure the continuance of the souls in the afterlife. The Old Kingdom monarchs rewarded the priests by making their office, and so whatever goods their lands produced, tax exempt. This policy empowered the priesthood to such an extent that, throughout Egypt's history, they would often rival the king in wealth and, eventually, effectively replace him.

The Cult of Amun

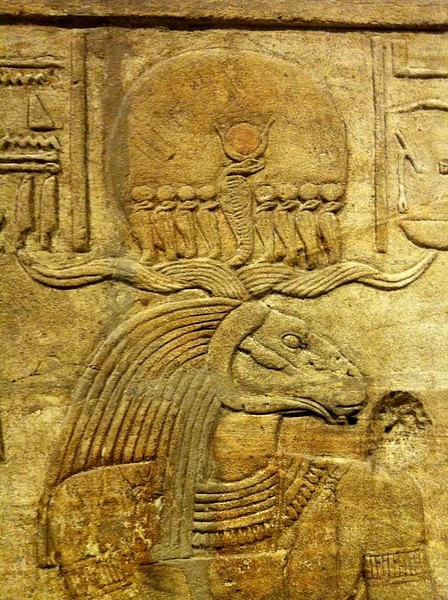

The word 'cult' as applied to Egyptian religion does not have the same meaning it does in the present day. The cult of a god referred to that particular deity's worship, beliefs surrounding him or her, and rituals enacted, much like a sect in modern day religion. Every major god or goddess had a cult following and a temple (or temples) in which they were thought to reside. Among the most powerful of these, from the Old Kingdom onward, was the cult of the god Amun.

Amun began as a local god of the city of Thebes in the Old Kingdom but rose to prominence as the city became more central in Egyptian political affairs in the Middle Kingdom (2040-1782 BCE) and, especially, in the New Kingdom (c. 1570-1069 BCE). During the New Kingdom a position was created which would eventually completely represent the power of Amun's cult: God's Wife of Amun.

God's Wives & the Rise of Amun

There were a number of god's wives by the time of the Middle Kingdom and probably earlier. These were royal ladies, usually the mother, wife, or eldest daughter of the king, who were granted the honorary title and would assist in rituals and at festivals. There was a God's Wife of Ra and a God's Wife of Ptah as well as a God's Wife of Amun but none of these women had any more political power bestowed on them with the title than they had before.

During the Second Intermediate Period (c. 1782-c.1570 BCE) Egypt was divided between the rule of the foreign Hyksos in Lower Egypt, Thebes in Upper Egypt, and Nubia to the south. The Theban prince Ahmose I (c.1570-1544 BCE) drove the Hyksos from the country, defeated the Nubians, and united Egypt under Theban rule; he credited his victory to the god Amun. Amun now became, not only the god of Thebes, but the savior of Egypt through his servant Ahmose I.

Ahmose I's mother, Ahhotep I (c.1570-1530 BCE), held the title of God's Wife of Amun and may have used it, as well as her position as king's mother, to put down a rebellion when Ahmose I was campaigning against the Nubians. This is the first instance of a God's Wife wielding political power; but it would not be the last. Ahhotep I conferred the title on her daughter (and Ahmose I's wife), Ahmose-Nofretari, and the position suddenly now carried greater responsibility and prestige and, with it, greater wealth.

God's Wife of Amun

Whereas in the Middle Kingdom the God's Wife would have been simply one aspect of a ritual or festival, she was now central to both. Further, she was allowed to enter the inner sanctum of the temple, the presence of the god, an honor previously reserved only for the high priest. Egyptologist Betsy Bryan of Johns Hopkins University identifies the duties of the God's Wife of Amun beginning with Ahmose-Nofretari:

1. Participation in the procession of priests for the daily liturgies of Amun. She was shown accompanying the priests called "god's fathers", a general designation that could include the top four priests of the temple, known by numbered position, i.e., "first priest", etc.

2. Bathing in the sacred lake with the pure priests before carrying out rituals.

3. Entering the most exclusive parts of the temple together with the high priest. This included the holy of holies.

4. With the high priest, "calling the god to his meal", reciting a menu of food offering being presented to Amun.

5. With the high priest, burning wax effigies of the enemies of the god to maintain the divine order.

6. Shaking the sistrum before the god to propitiate him.

7. Theoretically, as the "god's hand", assisting the deity in his self-creative masturbation. In this way and in her sistrum activity (a sexual allusion) she performed as the god's wife. (2)

These duties came with tax-exempt land, housing, food, clothing, gold, silver, and copper, male and female servants, wigs, ointment, cosmetics, livestock, and oil. While most of this payment was used in the performance of her duties, the lands would generate further revenue which would go directly to the God's Wife as her personal property, not to the temple.

Ahmose I could have elevated the position to diminish the power of the priesthood which, even during those eras of a weak central government, (the First and Second Intermediate periods), had continued to grow since the Old Kingdom. If this was his motivation, it served only to treat a symptom of the problem.

God's Wife & the Pharaoh

Hatshepsut (1479-1458 BCE) was honored with the position under her father Thutmose I (1520-1492 BCE) and later claimed she was actually the daughter of the god. After Hatshepsut came to power as queen, she conferred the title on her daughter Neferu-Ra in keeping with the tradition of the pharaoh selecting the new God's Wife. In doing so, she also kept the wealth of the position within the sphere of the crown and out of reach of the priests.

The God's Wives who follow Neferu-Ra throughout the New Kingdom and into the Third Intermediate Period (c. 1069-525 BCE) are almost all virgin daughters of the pharaoh but this did nothing to significantly curb the power of the cult of Amun. Akhenaten (1353-1336 BCE), famous as the religious reformer who introduced monotheism to Egypt and outlawed the old faith, may have been motivated by this problem of the priesthood's wealth and power far more than any mystical revelation concerning a one true god. Akhenaten abolished the position of God's Wife of Amun at the same time he disbanded the cult and closed all temples except those dedicated to his god, the Aten.

Following Akhenaten's death, however, the old traditions were resumed and the cult of Amun quickly regained their power. Egyptologist Helen Strudwick writes:

More than any other god in the Egyptian pantheon, Amun demonstrates the close link between religion and politics in ancient Egypt. During the New Kingdom, the Temple of Amun at Karnak was the largest in Egypt and its priests became so powerful economically as well as spiritually, that they threatened the supremacy of the pharaoh himself. (114)

This is most clearly seen in the Third Intermediate Period when Thebes was a theocracy ruled directly by Amun. This era was another in which the central government had weakened and rule was divided between Thebes in Upper Egypt and Tanis in Lower Egypt. The pharaoh at Tanis ruled directly but, at Thebes, the priests presided under the governance of Amun himself. Egyptologist Marc van de Mieroop explains:

The god made decisions of state in actual practice. A regular Festival of the Divine Audience took place at Karnak when the god's statue communicated through oracles, by nodding assent when he agreed. Divine oracles had become important in the 18th Dynasty; in the Third Intermediate Period they formed the basis of governmental practice. (266)

The priesthood had long become a hereditary position where fathers groomed their sons as successors in the same way a king did a prince. Each generation expanded the power and influence of the preceding one. The position of God's Wife had also become hereditary with the present woman choosing and grooming her successor.

Power Struggle & the Persian Invasion

The priests became so powerful that, when the Libyan king Shoshenq I (942-922 BCE) came to power he abolished the practice of priests succeeding their fathers and God's Wives choosing their successors and mandated that all priests and God's Wives were to be appointed by the pharaoh himself. He did not go so far as to ban the cult of Amun because the god had become far too popular and powerful by that time but he did what he could to check their power.

His example was followed by the Nubian pharaoh Kashta (c. 750 BCE) who appointed his daughter Amenirdis I as God's Wife of Amun, making her the most powerful woman in the country and the effective ruler of Upper Egypt from Thebes.

Kashta's son Piye (747-721 BCE) did the same when he appointed his daughter Shepenwepet II God's Wife and entrusted her with the rule of Upper Egypt when he led his campaign against Lower Egypt. This same paradigm was followed by the kings who succeeded Piye until the Persian invasion of 525 BCE crushed the power of the cult of Amun and ended the position of God's Wife.

The title would continue to be held in Nubia, however, where the cult flourished at Meroe. The exact same pattern seems to have repeated there as in the thousands of years of Egypt's history where the king had to struggle against the power of the priests for supremacy. Finally, in c. 285 BCE, King Ergamenes of Meroe had all the priests of Amun massacred to resolve the problem and abolished the position of God's Wife. The cult would continue, though, and exert influence in Meroe and elsewhere until it was finally replaced by the new religion of Christianity.