Uat-Ur was the ancient Egyptian name for the Mediterranean Sea (also known as Wadj-Wer) and is translated as 'the Great Green'. Uat-Ur was understood as a living entity imbued with the spirit of the divine which, like all other aspects of the natural world, was a gift from the gods.

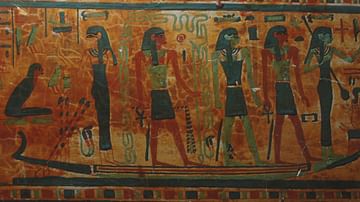

Uat-Ur was the sea itself, not a god of the sea, but was sometimes pictured as a male with breasts heavy for nurturing and with skin resplendent with the shimmer of rolling waves. Uat-Ur is often shown in company with images of the Nile River, linking him sympathetically with the 'mother of all men' which was one of the titles the ancient Egyptians gave to the Nile.

Egypt's Insular Culture

The Egyptians were not a great seafaring people. They were as interested in travel to foreign lands as they would have been in an earthquake. To the Egyptians, their land was a perfect world given by the gods, created from the primordial ben-ben upon which Atum first stood when dry land rose from the chaotic swirl of waters at the beginning of time.

Their god of chaos was Set (also known as Seth) who was associated with the lands beyond the boundaries of Egypt's Nile River Valley and who had as his consorts two foreign goddesses, Anat from Mesopotamia (Syria) and Astarte of Phoenicia. It was no coincidence that Set, who eventually came to be seen as the first murderer, was linked to the regions beyond Egypt's borders: the Egyptian culture was fairly xenophobic and distrusted foreigners and their influence.

Uat-Ur, therefore, did not feature prominently in Egyptian literary texts or religious writings. There are no great epics in Egyptian literature mentioning the "wine dark sea" as one finds in Homer of the Greeks. In the story of The Tale of the Shipwrecked Sailor (c. 2000 BCE) the main character is a servant, not a military hero, who is simply going about his master's business of trade when he is shipwrecked on the Island of Punt and meets the Lord of Punt, a gigantic serpent. The servant is not interested in any of the magical and glorious rewards one might find on Punt because he feels that anything he wants is back home in Egypt.

The Lord of Punt finally releases him to go home where he tells his master all that has befallen him. The Tale of the Shipwrecked Sailor perfectly epitomizes Egyptian cultural values as the main character is a common man aware of the concept of ma'at (harmony) and his duty to his social superior. When he reaches the Island of Punt he observes the same protocol he would back in his homeland with the significant difference of refusing to accept the Lord of Punt's offers of generosity. Whatever this foreign lord has to offer him, he knows, cannot compare with what he has left behind in Egypt.

The Tale of Prince Setna

Another story, this one from the Ptolemaic Period (323-30 BCE), is The Tale of Prince Setna (also known as Setna I). Although there are many ways to interpret this story, and many lessons an ancient Egyptian audience would derive from it, one would have been not to involve one's self with strangers. In this story, Prince Setna sees an exotic woman named Taboubu and falls in love with her. He has never seen any woman as beautiful before in his life, lusts after her, and devotes himself to her completely after just meeting her.

Taboubu refuses his request to spend an hour with him in his hometown of Memphis and instead invites her back to her place in Bubastis. Even though Bubastis is an Egyptian city, it is still removed from Setna's home city of Memphis and he must take a boat to reach it. Once there, Taboubu makes requests of the prince which he grants instantly but she then asks for more and then more significant sacrifices on his part until, finally, he agrees to have his children murdered just to sleep with her. Before he can finally get her to bed, though, she vanishes and he finds himself naked in the streets of the foreign town. Only then is he told that his experience with Taboubu has all been a dream, his children are alive and well, and he thanks the gods for his good fortune.

This story, like The Tale of the Shipwrecked Sailor, expresses important cultural values in that Prince Setna is easily led astray by a woman he has never seen before. He is essentially warned by the gods through this dream-experience not to become involved with foreign women. The steady progression of Taboubu's requests from minor favors to capital crimes mirrors the Egyptian view of foreigners seeming to be innocent acquaintances at first but who eventually bring destruction.

Possible Origin of Xenophobia

This fear of outsiders might be traced back to the latter part of the Predynastic Period in Egypt (c. 6000-c.3150 BCE) when outside influences began to affect Egyptian culture. During the period known as Naqada III (c.3200-3150 BCE) significant changes were set in motion in Egypt through trade with Mesopotamia. The construction techniques and technology used in creating the large tombs of Abydos and Hierakonopolis are Mesopotamian in origin and, as trade increased with regions of Palestine, new concepts and religious ideas were introduced. Increased trade with foreign lands led to the empowerment of some cities and the loss of prestige for others.

The power became concentrated in cities such as Naqada, Thinis, and Nekhen of Upper Egypt which then conquered Lower Egypt c. 3150 BCE resulting in the first king of a unified country, Narmer (also known as Menes). This event could possibly have been traumatic enough for those of Lower Egypt to have produced a fear of the outside world which came to be expressed in stories, wisdom texts, and legends.

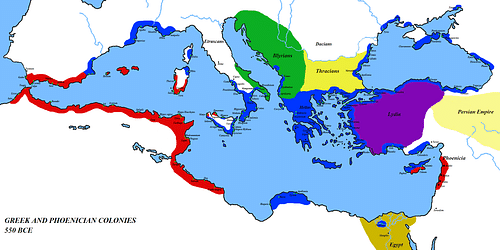

However the original distaste for the outside world came about is actually immaterial, however, since the deep love the Egyptians had for their land caused them to feel there was no other region worth visiting. The reason why there is no Egyptian empire of the breadth of the Assyrian or Roman empires is not because they lacked military skill but because they did not want to travel that far beyond the borders of the country. The great military campaigns of Egyptian kings were all to neighboring regions such as Syria, Palestine, and Nubia. Although some kings of the New Kingdom (c.1570-1069 BCE) campaigned in Mesopotamia, this was unusual and they did not penetrate very deeply into the region.

The Egyptian belief in the afterlife as a perfect reflection of their time on earth led them to fear dying in a foreign land where they would have a harder time finding their way to the Field of Reeds than they would if they died in their own country. An important aspect of their culture was the mortuary rituals which needed to be performed precisely according to tradition in order for them to find peace in the afterlife. Egyptians who could afford it even paid high prices to be buried at Abydos, one of the god Osiris' chief centers of worship, just so they could be nearer to him and have a better chance to reach the paradise promised by the religious texts.

Uat-Ur and the Outside World

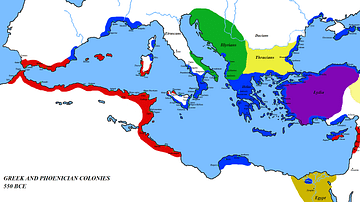

This is not to say that the Egyptians did not engage in trade as they most certainly did. The Greek colony of Naucratis was extremely important to Egyptian and Greek commerce as was the more famous port of Alexandria close by. The Egyptians traded papyrus, linen, gold, leather, and grains for such goods as wood, marble, olive oil, copper, and wine. Beer was considered the drink of the gods in Egypt (as it was in Mesopotamia) and wine was a novelty. The cross-cultural exchange through trade was extremely important for both cultures but, in keeping with their traditional views, Egypt resisted cultural transference from Greece while Greeks readily adapted Egyptian views, religious beliefs, and technology.

Uat-Ur may not have played an important role in Egyptian beliefs but it was still personified as a living being. To the Egyptians, the whole world was alive with the spirit imbued by the gods and every tree or breeze, every place by a flowing stream, was a gift the gods had given and could also live in. The Mediterranean was not seen as simply a body of water but as a living entity with a personal name, Uat-Ur, because all of the world was alive with the spirit of creation to the ancient Egyptians. Even though they were not the great seafarers or explorers that the Greeks were, they still honored the sea with recognition and respect as another aspect of the world created and sustained by the gods.