The Children of Heracles (Heraclidae) is one of Euripides' lesser known and least popular works, as is the myth surrounding the tragedy play. Its date is also uncertain, possibly written in the late 430s or early 420s BCE. The play revolves around the mother and children of Heracles (Hercules) and their attempt to find sanctuary from the forces of the king of Argos, a king who wishes to have them killed. It is possible that the play as it exists today has been revised later by other writers.

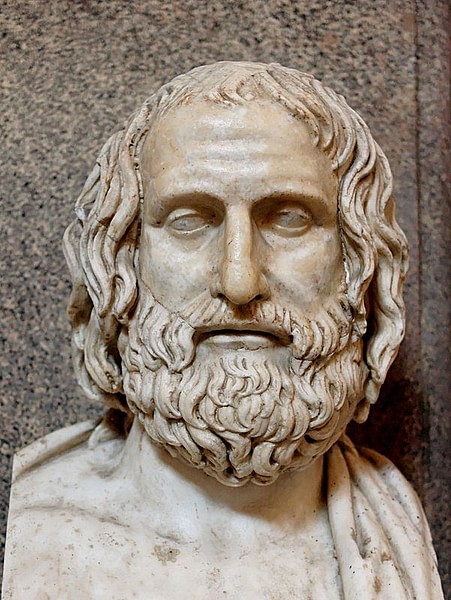

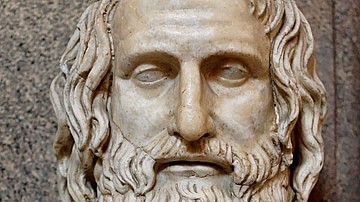

Life of Euripides

The Children of Heracles was written by the youngest of the great trilogy of Greek playwrights Euripides. Little is known of Euripides' early life. He was born in the 480's BCE on the island of Salamis near Athens to a family of hereditary priests. He was married and had three sons, one of whom, also named Euripides, became a noted playwright. He preferred a life of solitude, alone with his books and there are even stories that he lived isolated in a cave. Unlike the elder Sophocles, Euripides played little or no part in Athenian political affairs; the one exception was a brief diplomatic mission to Sicily. He wrote over 90 plays, of which, 19 have survived which is more than any of his contemporaries. The poet made his debut at the Dionysia competition in 455 BCE, not winning his first victory until 441 BCE. Unfortunately, his participation in these competitions did not prove to be very successful with only four victories; a fifth came after his death for a trilogy which included Iphigenia in Aulis and The Bacchae.

With the Peloponnesian War waging, Euripides left Athens in 408 BCE to live the remainder of his life in Macedonia. Many believe he wrote some of his best plays there. Although often misunderstood during his lifetime and never receiving the acclaim he deserved, he became one of the most admired of all poets decades later, influencing not only Greek but Roman playwrights. Years after the playwright's death, the Greek philosopher Aristotle (384-322 BCE) called Euripides the most tragic of the Greek poets. Classicist Edith Hamilton in her book The Greek Way agreed when she wrote that he was the saddest of all of the greats, a poet of the world's grief:

He feels, as no other writer has felt, the pitifulness of human life, as of children suffering helplessly what they do not know and can never understand.” (205)

She added no poet's work was “so sensitively attune as his to the still, sad music of humanity, a strain little heeded by that world of long ago” (205). It is said that when Athenians speak of “the poet” they are referring to Euripides. In his book Greek Drama, Moses Hadas said that audiences would come to appreciate his style and outlook viewing his plays as more sympathetic than those of his contemporaries.

Synopsis of the Play

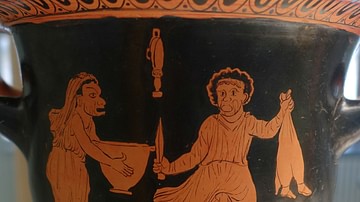

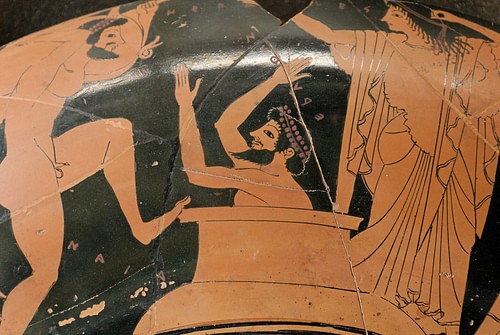

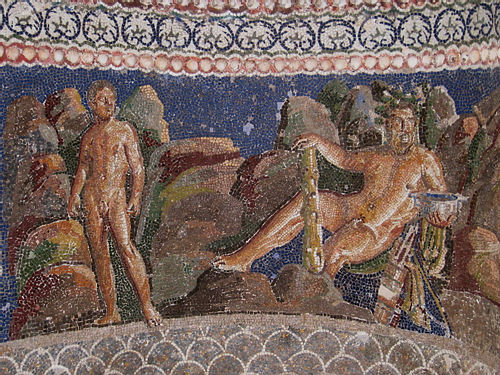

The play begins after the death of the mythical hero Heracles. He had been enslaved by King Eurystheus of Argos/Mycenae and compelled to complete his twelve labors. Heracles was survived by his young children, his mother Alcmene, and cousin and long-time companion Iolaus. His family had escaped the clutches of the king and traveled the length of Greece looking for refuge. The king vowed to capture the family and return them to Argos to face certain death, threatening cities with war if any gave them safe harbor. At last, they arrive in Athens and rest at the temple of Zeus. The sons of Theseus - Demophon and Acamas - promise them safekeeping. Despite a stern warning from Eurystheus' herald of a potential war, the family is assured refuge. Sadly, a prophecy dictates that a virgin must be sacrificed for Athens to win a future war.

When the king of Athens, Demophon, states he will not sacrifice an Athenian maiden, one of Heracles' daughters - her name is never mentioned - volunteers; unfortunately, the play fails to mention if the sacrifice is ever made. The Athenian forces, led by Heracles' elder son Hyllus and a rejuvenated Iolaus (Heracles' companion during the 12 labours), is victorious and the defeated Eurystheus is brought before Alcmene who demands his immediate death. Although many Athenians do not want him killed, the play ends with the captured king saying that his spirit will protect the city and people of Athens in the future.

The Cast of Characters

The cast of characters includes:

- Heracles' former companion Iolaus

- Heracles' mother Alcmene

- King Eurystheus of Argos

- King Demophon of Athens

- King Acamas of Athens (silent)

- an unnamed maiden (daughter of Heracles)

- and a herald, a messenger, a servant, and the usual chorus of old men.

The Play

The play begins at the altar of Zeus at Marathon. Iolaus, the long-time companion and relative of the Greek mythical hero Heracles, speaks aloud,

… I alone shared in most of the labours of Heracles while he was among us. And now that he has his home in the sky, I have taken his children here under my wing, giving them the protection I stand in need of myself. (97)

He declares how the King Eurystheus of Argos wishes to kill them. He, Heracles' children and mother Alcmene have wandered from city to city seeking refuge. Hyllus, the eldest son, is away searching for a place for them to build a home. No one, out of fear of the Argive king, will give them asylum. At last, they have arrived on the outskirts of Athens. Suddenly, in the distance, he sees the herald of the Argive king making his way towards them. He beckons the children to come to him. He addresses the herald, “You loathsome creature, how I wish you would die, you and the man who sent you…” (98)

Ignoring the old man's comments and looking directly at Iolaus, the herald replies, “You must leave this place for Argos, where the penalty of death by stoning awaits you.” (98) Iolaus defiantly refuses him and says that the herald will never take him or Heracles' family by force. He pleads aloud for the people of Athens to keep them safe:

O men of Athens, dwellers in this land from earliest days give us your help. We are supplicants of Zeus of the Agora, yet violence is being used on us and our holy branches are defiled, disgracing your city and dishonouring the gods. (99)

A chorus of old men hears his cries and asks Iolaus why he has thrown himself upon the ground. Iolaus introduces himself and the children to the chorus and says they have come to Athens to seek mercy. The herald quickly warns the chorus that the old man and family belong to King Eurystheus. The chorus, however, is not intimidated and responds that he should have spoken first to the rulers of the land and shown the proper respect. The herald is then told that Demophon son of Theseus is the ruler.

Shortly, the king and king's brother Acamas enter. Demophon is quickly told how Iolaus and Heracles' family seek asylum from the Argive king. The Athenian king, obviously annoyed, looks towards the herald, “… the clothes he wears, the shape of his cloak are a Greek's, but he is behaving like a barbarian.” (101) The herald responds, “Argos is my home …King Eurystheus sends me here from Mycenae to fetch these people.” (102) He warns Demophon that if he chooses to give them shelter “the matter becomes one of armed conflict.” However, if the herald is permitted to take them away and return to Argos, the city of Athens will enjoy the friendship of Mycenae. Ignoring the herald's warning, the king is compelled to accept Iolaus plea. “Where is the justice in leading off supplicants against their will?” (104) He orders the herald to return to Argos and tell his king that he will never take the family of Heracles by force. When the herald tries to seize the children, Demophon raises his staff and stops him. “Lay a finger on them and you'll regret it at once,” (105) The herald exits but tells the Athenian king that he and his king will return with an armed force. Iolaus is thankful, for they have found friends and kinsmen. Demophon leaves to “muster my citizens.” He will send scouts to watch for the Argive.

Although the herald has gone, the chorus chimes in when they say, 'You may thirst for war but do not, I pray, ravage with your spear the city where the Graces have their happy home.” (107) The king returns and tells Iolaus and the others that the Argive army has arrived, for he has seen them with his own eyes. However, he bears sad news: according to the oracle, a sacrifice must be made - a virgin girl whose father is of noble blood. Regrettably, he will not sacrifice his daughter or one of any Athenian father. Iolaus is at a loss. “Where are we to turn? What god has been denied the tribute of our supplicant garlands?” (109) He begs the Athenian king to have himself given to the Argive, but Demophon refuses.

A maiden - a daughter of Heracles - steps forward. “I am myself ready to die, good old man, and to take my stand at the sacrifice, I need no order.” (110) Iolaus rejects her wishes and suggests that lots should be drawn instead, but the maiden rejects this idea. She believes she must give her life freely - no compulsion. She exits. The chorus tells Iolaus not to torment himself, for she dies an honourable death - one of glory. Just then a servant of Hyllus arrives. Alcmene is called to meet him. The servant tells her that her son has made camp outside town. He and his army will be the left wing of the Athenian forces. As the servant begins to leave to join his master, Iolaus speaks, “I'll come along with you; we are of one mind in this, wanting to help our friends by standing shoulder to shoulder, as it is right we should.” (115) The servant is hesitant: Iolaus is too old, and he is incapable of fighting. However, Iolaus is insistent. Taking armour from the temple, he prepares to leave. Alcmene begs him to stay to protect the family, but the old man believes he must fight. He leaves.

Shortly, a messenger arrives. He brings news of a victory. Alcmene asks of Iolaus. She is told that “his contribution to the victory was outstanding, thanks to the gods.” (118) Surprisingly, he was an old man no longer - changed back to a young man. Alcmene listens to the messenger tell of the Athenian victory and the capture of Eurystheus - even how Iolaus spared the king's life. 'It was out of respect for you he wanted you to feast your eyes on Eurystheus in the hour of your victory, when he had become yours to do with as you pleased.” (121) The king, of course, had wished to avoid the meeting. Against the king's wishes, a servant brings him before Alcmene. She speaks, “You loathsome creature, is this you here? Has justice caught you in her net at last? (122) She tells him that he will soon meet his death. Unfortunately, the servant reminds her that Athenian law will not permit it. He asks if she will go against the law. She ignores the servant and says that she, herself, will end his life.

Eurystheus speaks. He will not plead for his life:

Athens has shown her restraint, in sparing me' she honours the gods far more than she respects your hatred of me … if I die, you must call me by two names: the victim whose blood demands vengeance and the hero of noble heart. (124)

To quit life would give him no pain. Still intent on killing him, Alcmene says, “I will kill him then hand over his corpse to the friends who come for him. As far as his person is concerned, I will not go against Athenian wishes and he by his death will give me the revenge I seek.” (124) The king says he will present the city with a gift: “blessings greater than you now imagine. When I am dead you will bury me where fate prescribes.” (124) He will lie under the soil of Athens extending goodwill and protection. Alcmene tells the people of Athens that he is an enemy and yet will benefit the city in death. She orders him to be taken away and fed to the dogs. The chorus tells the servant, “On your way, men! No guilt shall fall on the king's head from actions of ours.” (125)

Assessment

The Children of Heracles is one of Euripides' lesser-known works, and, according to many classicists may have been rewritten over the years by other poets. Over all, the poet's works have influenced countless others in both Greece and Rome. More of his works have survived than any of his contemporaries. Like other playwrights of the era, Euripides makes reference to Greek mythology, and, in this case, it's the hero Heracles. In the retelling of the story, Heracles is dead; however, his nemesis, the king of Argos, pursues his family, wishing to bring them back to Mycenae to face certain death. They are given shelter in Athens by King Demophon and his brother Acamas. A war ensues, and Athens is victorious. The family, at last, has found a home.

One question may disturb the reader: who is the unnamed sacrificial maiden. While it is obvious that she is the daughter of Heracles, her name and age are never given. Lastly, does Alcmene actually kill the king as she vows to do? The king is taken away at the very end of the play, but his fate is left in question. He is, however, viewed as being a hero. According to the editors of Euripides: Medea and other Plays, “The play dramatizes a reversal of fortunes: from being powerless and persecuted the family of Heracles rise to a position of security and strength.” (92) While many of the characters do not appeal to the audience's sympathies, it is still seen as “fully worthy” of Euripides in its ingenuity of plot and the strength of its language. (93)