The Salem Witch Trials were a series of legal proceedings in Salem, Massachusetts in 1692-1693 resulting in the deaths of 20 innocent people accused of witchcraft and the vilification of over 200 others based, initially, on the reports of young girls who claimed to have been harmed by the spells of certain women they accused of witchcraft.

The initial accusers were Betty Parris (age 9) and her cousin Abigail Williams (age 11) who were supported in their claims by Ann Putnam the Younger (age 12) and Elisabeth Hubbard (age 17), but once those accusations were made, many others not only supported the girls but brought charges against their fellow citizens, sparking a witch hunt in Salem and the surrounding communities.

At the heart of the trials and later executions were religion and superstition in Colonial America. The Bible, in the Book of Exodus 22:18, states "Thou shalt not suffer a witch live," and this was adhered to as closely as any other biblical injunction and encouraged by the Salem Village minister of the time, the Reverend Samuel Parris (l. 1653-1720). Parris was the fourth minister called by the Salem Village congregation. Earlier ministers had left after relatively brief stays, and Parris was faring little better in his ability to mediate disputes between neighbors until he managed to focus their energies on accusing each other of witchcraft. The underlying tensions of the community found expression in the persecution of marginalized members – and then those well-respected – in the community which resulted in the execution of 20, self-exile, loss of status, or death in jail while awaiting a court appearance.

As early as 1695, criticism was leveled against the magistrates of Salem for the deaths and persecution of the innocent and this opinion only gained ground afterwards. Between 1700-1703, petitions were filed to have the convictions reversed and the accused exonerated, and in 1711, compensation was authorized for the families of those unjustly executed. Since that time, the Salem Witch Trials have been referenced simply as "witch trials" or "witch hunts" in connection with any unfounded, unfair, and baseless claim against a person or the ideals that person stands for and the event has been given iconic status in the USA and elsewhere.

Colonial Belief in Witchcraft

Legal documents and testimonies of the time establish that there were a number of citizens who did not believe in witchcraft, but the majority – in the New England Colonies as well as the Middle and Southern English Colonies – certainly did. This belief was encouraged by the Bible through stories such as the Witch of Endor (I Samuel 28:3-25) and the line from the Book of Exodus mentioned above. The Bible was understood as the inerrant word of God and made clear that witches were as much of a reality as anything else; questioning the existence of witches meant questioning the divine authority of the Bible.

A belief in witchcraft was further encouraged by the need to explain the seemingly unexplainable. If a pious person or a child or young bride should suddenly fall ill or die, it might be attributed to God’s mysterious will but could as easily be explained by witchcraft and the workings of the devil. Although it may seem strange and irrational to a modern-day audience, the belief was also supported by colonists’ interpretation of everyday experience. If Neighbor A asked to borrow some candles from Neighbor B and Neighbor B refused the request, and if Neighbor B later became ill or their house caught fire or their horse died for no apparent reason, Neighbor A might be accused of having cast a spell to cause the otherwise inexplicable misfortune.

A belief in witches did not originate in the colonies, however, as England – and Europe overall – had been persecuting those accused of witchcraft for centuries. One of the most famous witch trials in English history was that of the Pendle Witches in 1612 in Lancashire which resulted in the execution by hanging of ten people convicted of witchcraft. The records of the proceedings were published in 1613 and widely read, and the case was popularized again in 1634 when one of the accusers was herself accused of witchcraft. The 1634 case was further popularized by the melodrama The Late Lancashire Witches by Thomas Heywood (l. c. 1570-1641) and Richard Brome (l. c. 1590-1652), which ends with a supposition of the guilt of the accused.

This was almost always the foregone conclusion of an accusation of witchcraft since it was understood that no one would bring such a serious charge against another without good reason. Accusers seem to always have believed that their word and anecdotal evidence was all the proof a court needed to convict, and while this may have been true of popular opinion, courts did try to weigh objective evidence before handing down a conviction, even if the paradigm of guilty-until-proven-innocent was largely adhered to. This was certainly the case with the Salem Witch Trials of 1692-1693 during which over 200 people were accused of witchcraft in Salem Village, Salem Town, Andover, Ipswich, and Topsfield; 30 were found guilty and 20 executed, most by hanging.

Social & Religious Context

Tensions were already high in both Salem Town and Salem Village in 1692 and had been for some time. The citizens of Salem Village resented the greater affluence of Salem Town as well as its presumption in controlling the village’s affairs. Salem Village had no civil government of its own and was under the jurisdiction of Salem Town. All citizens of both were required to attend Sunday worship services, but Salem Town refused to allow Salem Village to have its own meeting house and so villagers had to travel to the town on Sundays, no matter the weather, which they came to resent.

Salem Village eventually hired their own minister but refused to pay him and so he left. The second minister, George Burroughs, experienced the same problems and resigned but remained in the village. A third minister also resigned, and this contributed to Salem Village’s reputation, as held by Salem Town, as contentious and petty. The fourth minister was Samuel Parris, a failed merchant who had attended Harvard University but never completed his course of study. He seems to have become a minister as a second career choice. In 1689, Salem Village was allowed to form its own church with Parris as their pastor. Scholar Brian P. Levack comments:

Parris proved to be an unfortunate choice: a failed and bitter merchant who resented those who succeeded in the world of commerce, he fueled local hostilities. Parris gave a series of inflammatory sermons that translated faction division into a cosmic struggle between the forces of good and evil. In the minds of his supporters, Salem Town became the symbol of an alien, corrupt, and even diabolical world that threatened the welfare of Salem Village. Because supporters of Samuel Parris perceived their enemies as nothing less than evil, it was but a short step for them to become convinced that those aligned with the town and its interests were servants of Satan. (403)

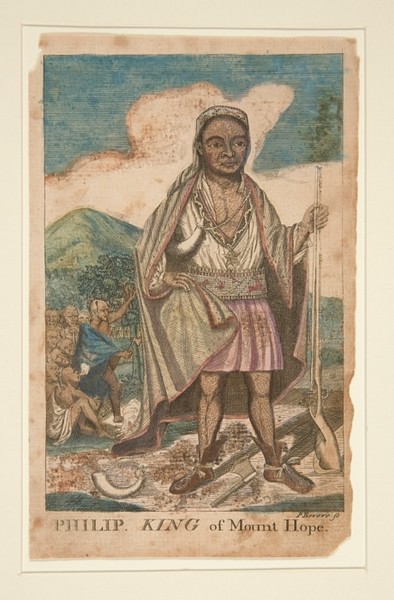

Tensions increased further with the arrival of immigrants in the area who were members of minority Christian sects, such as the Quakers, who were considered threats to the Puritan vision of the Salem community. Perpetual fear of unseen and unexpected danger had been present in the communities since the outbreak of King Philip's War (1675-1678) when King Philip (also known as Metacomet, l. 1638-1676) of the Native American Wampanoag Confederacy launched an assault on the settlements of New England that killed hundreds and destroyed a number of settlements.

In the midst of these various tensions, in February 1692, Samuel Parris’ daughter Betty and his niece Abigail Williams, began exhibiting strange behavior – crawling around the floor, hiding under furniture, contorting themselves, screaming, and hurling objects – which, lacking any other explanation after they were examined by a physician, was blamed on witchcraft. Shortly afterwards, Ann Putnam the Younger and Elizabeth Hubbard, then Mary Walcott, Mercy Lewis, and Mary Warren – all friends of Betty Parris and Abigail Williams – began exhibiting the same signs. When Samuel Parris asked his daughter and niece who had cast the spell that was tormenting them, they named three women – Sarah Good, Sarah Osborne, and the Parris’ house-slave Tituba – and Salem Village was plunged into a witch-hunting frenzy.

Salem Witch Trials

Sarah Good was a homeless woman who often begged for charity and had been taken in by Samuel Parris for a short time until he threw her out for "malicious behavior" and ingratitude. Sarah Osborne was a wealthy landowner who had not attended church in over three years, claiming a recurring illness, making her as much of an outcast as Good. Tituba was possibly an Arawak of Caribbean origin who was kidnapped, enslaved, and sold to Samuel Parris in Barbados, where his family had a plantation. She was the family’s house-slave and looked after the children, often entertaining them with ghost stories and tales of demons and magic.

Tituba confessed (later revealing Samuel Parris had beaten the confession out of her) and supported the girls’ accusation of Good and Osborne. Good, as noted, was already despised by the Parris family and Osborne, due to her land deals, had adversely affected the finances of Ann Putnam the Younger’s father. Tituba popularized the concept of witches riding on broomsticks and conversing with 'familiars' – spirits in animal form – as well as associating with demonic figures and casting malicious spells. Osborne was hanged as a witch in May and Good in July of 1692, maintaining their innocence to the end; Tituba, since she had confessed, was left in jail because Parris refused to pay the fees which would have released her. She was finally sold for the price of the jail fees and disappears from history.

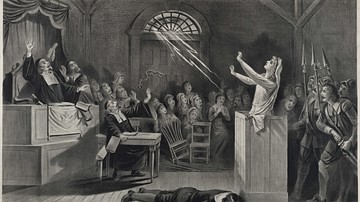

The accusations against the three marginalized women in February 1692 were only the beginning, however, as more people were accused in March. Two of them, Martha Corey and Rebecca Nurse, were members in good standing in the church. Corey had questioned the validity of the girls’ accusations, insinuating they were lying for personal reasons, and so was charged as a witch for denying the existence of witches. Nurse was accused by the Putnams who claimed her 'specter' was harassing them. The use of 'spectral evidence' was admissible in court as the concept had been addressed by the well-respected Puritan theologian Cotton Mather (l. 1663-1728) whose works were especially popular among the citizens of Massachusetts.

Spectral evidence was simply accepting the word of an accuser over that of the accused as in the case of Martha Corey where the girls cried out in court that her specter was tormenting them and a yellow bird, invisible to everyone but them, was feeding at her hand. Nurse and Corey, both in their early 70s, were hanged. Their convictions heightened the hysteria further in that, if two elderly church-going women in good standing could be witches, anyone could. Corey’s husband, Giles, was accused when he defended her. He refused to stand trial and was executed by pressing – crushed to death by weights – in order to extract a confession of guilt. As he never confessed and was never convicted, his last will was honored and his lands went to his heirs, as he intended, instead of being taken by the Putnam family who had accused him.

Once spectral testimony came under attack and once confessors began to recant, the court found itself in an extremely awkward position…As the eagerness of the court to convict collided with a growing chorus of opposition to its proceedings, the governor felt that he had no choice but to suspend the trials and reassess the situation. (407)

The trials were stopped and pardons issued for those still in jail in May 1693. Although it is well-documented that 19 people were hanged and Giles Corey crushed to death, others died in jail awaiting trial, and over 200 had their reputations damaged if not irreparably ruined. The accusers were never called to account because no one involved doubted the reality of witches and their power to harm nor of Satan and his ability to deceive in order to destroy. After the hysteria died down, the accusers went on with their lives as before.

Conclusion

Those who had been accused and pardoned, as noted, were not as lucky and lived on with the stigma of the event or moved elsewhere. Three years later, in 1696, the General Court mandated a day of fasting and repentance for the trials on 14 January 1697. Judges who had taken part in the trials publicly repented and asked forgiveness of the community. Beginning in 1700, petitions were filed by family members with the colonial government of Massachusetts to have the convictions overturned, and in 1711, 22 people were exonerated and financial compensation authorized. This pattern continued over the next ten years but not all who had been convicted were cleared even then. The names of all the people convicted were not cleared, in fact, until 2001.

The Salem Witch Trials, as the most infamous event of its kind, has generated a number of myths from the time people began writing about it c. 1700 to the present. Among the most persistent is that "witches" were burned at Salem even though there is no evidence to support this claim. No "witches" were burned at Salem; they were all hanged. Until recently, those convicted were thought to have been hanged on Gallows Hill, conjuring images of a somber death march up the hill to the place of execution, but the Gallows Hill Project of 2017 debunked this myth, establishing that the hangings took place at the bottom of the hill at the far less dramatic area known as Proctor’s Ledge.

It has also been claimed that the majority of those accused were poor, marginalized women, but this has also been challenged and debunked. People of all social classes were accused and convicted, women and men – and, actually, two dogs – for any reason at all. George Burroughs, the second minister to resign at Salem Village, was accused and convicted because he seemed to possess unnatural strength, another woman was convicted because she was able to walk the dusty streets of Salem Village without dirtying her clothing, and Martha Corey, as noted, was executed as a witch for denying witchcraft even existed.

Over the years, many theories have been suggested to explain the Salem witch hysteria and trials. One theory, popularized in the 1970s, is that the colonists were poisoned by ergot fungus on their rye crop in 1692 which caused them to hallucinate, but this does not explain the continuing hysteria throughout 1693 nor the fact that there were many who still believed in witches and the justice of the trials afterwards. Witch trials had been conducted prior to 1692 and would be afterwards throughout the colonies. Class frictions between Salem Village and Salem Town have also been cited as a possible cause, but, although these added to the tensions of the time, they did not actually cause the hysteria. Of the first people accused, only Osborne had connections to Salem Town, the other two were firmly of Salem Village.

The most likely cause of the witch hysteria of 1692-1693 at Salem was religious belief coupled with societal tensions. No one will ever know what caused the girls to make the accusations which started the panic, but once made, they confirmed what was already believed by the colonists. American playwright Arthur Miller’s The Crucible cast the Salem Witch Trials as an allegory of the McCarthy hearings of the 1950s which sought to root out communism in the United States. In this play, Miller was drawing attention to the dangers of ideologies which depend on confirmation bias in order to thrive. In both cases, the accusers were operating on a belief in threatening agents in their midst they needed to defend themselves against. The people of Massachusetts already believed in witches because religion in Colonial America encouraged it – they did not need ergot or anything else – all that was required was a physical manifestation of what they feared to confirm what they already knew to be true and act upon it.