Roman medicine was greatly influenced by earlier Greek medicine and literature but would also make its own unique contribution to the history of medicine through the work of such famous experts as Galen and Celsus. Whilst there were professional doctors attached to the Roman army, for the rest of the population medicine remained a private affair. Nevertheless, many large Roman households had their own medical specialist amongst their staff and with the spread of literature on the topic the access to medical knowledge became ever wider, treatments became more well known, and surgery became more sophisticated.

Sources

Undoubtedly the richest source available is the literature Romans dedicated specifically to the subject of medicine. Many have been lost but some of the medical texts of several of the more successful medical experts in Roman times have survived because they were sufficiently popular, both in their own time and for centuries after, so that they were copied by hand many times, thus, increasing the chances of their survival from antiquity. The records of military hospitals (valetuduniaria) can also provide insight into the ailments the camp doctors (medici) and their assistants (capsarii) had to deal with. These obviously included the wounded (volnerati) but also the sick (aegri) and those with eye problems (lippientes). From the 2nd century CE there were also illustrated works which showed exactly which plants and herbs were good for which medical problem.

Another source of information on ancient medicine is tombs, for example, a tomb in a cemetery in Rome of a successful midwife, one Scribonia Attice, has decorative terracotta plaques which show medical scenes such as a birth where the patient sits in a specially designed chair where the infant can drop through the seat during childbirth. The chair slopes slightly back, has handles to grip and a perforated seat. Such reliefs can also show medical instruments (instrumentaria) such as scalpels, probes and hooks but hundreds of these have in fact survived themselves, typically excavated from the sites of hospitals in military camps, cemeteries and sites like Pompeii. Forceps, tweezers, wound retractors, collecting cups, needles and various sized scalpels, often beautifully made with steel blades, have survived to illustrate the details of Roman medicine.

Greek Influence

By the 2nd century BCE Greek doctors were well established in Rome but the first records of the influence of Greek medicine on Roman medical practice go much further back. The first evidence of this process is the construction of the temple of Apollo Medicus in Rome in 431 BCE in response to the devastating plagues which were sweeping Italy at that time, as Apollo was credited with a healing power For the same reasons Asclepius (Aesculapius) was adopted in 292 BCE with the Romans taking the god's sacred snake from Epidaurus, perhaps the most famous of the Greek healing sanctuaries. The snake did make an escape in transit, once at the port of Antium and again on arriving in Rome but, resurfacing on the Tiber Island, a sanctuary to the god was established there. Just as at Epidaurus, patients visited the site in the hope of receiving divine instruction and remedies.

Perhaps the first known Greek medical practitioner to ply his trade in Rome was Archagathus of Sparta who arrived in 219 BCE and who is credited with first introducing Greek medical practice to the Romans. Specialising in healing battle wounds, he also gained a reputation for solving skin problems. Pliny the Elder, in the 1st century CE, covered medicine in his Natural History but he was a strong critic of Greek doctors, complaining of their high fees, immoral conduct with patients and general malpractice. Pliny had more faith in the traditional Roman medicine administered by the head of each family. These gentle remedies were in stark contrast to the cutting and chopping of men like Archagathus, whom he labelled the carnifex or 'Executioner'.

General Approach

Despite criticisms of the Greek doctors they were, nevertheless, extremely popular and many a Roman household had one as part of the staff. In addition, the Greeks were able to bring their knowledge of the 5-4th century BCE Hippocratic Corpus with its classic division of medical treatment into diet, regimen and surgery. Also, the Greeks brought the latest trends from Alexandria where practitioners were greatly increasing their knowledge of the human body through the dissection and vivisection of condemned criminals. The more canny Greek doctors were also able to adapt their approach to Roman tastes. For example, Asklepiades of Bithynia (d. 90 BCE) was famous for his 'soft' therapeutic treatments such as massage, bathing, and gentle exercise mixed with a prescription of water and wine.

The most influential work on drugs was Materia medica by Dioscurides of Anazarbus written in the 1st century CE. In it Dioscurides mentions a vast number of herbal and plant remedies along with such medicinal classics as poppy juice and the autumn crocus, containing morphine and colchicine respectively. He also describes the helpful properties of certain stones if worn as amulets. For example, green jasper was thought good for stomach problems and especially popular were the okytokia stones which were worn by expectant mothers hoping for a quick childbirth. The great Roman medical scholar Galen took many ideas from this work and it continued to be an important reference up to the 5th century CE and beyond.

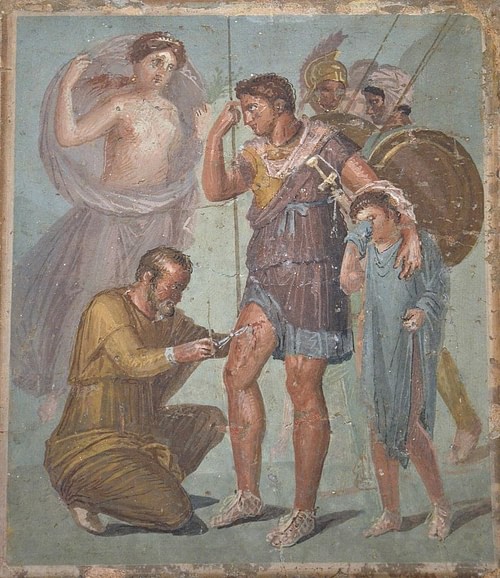

As was typical in other ancient cultures, surgery, because of the risks involved, was usually employed only as a last resort. There was also concern for the patient's comfort and a realisation of the futility of causing further pain when recovery was unlikely. Surgery, then, was usually limited to the surface of the body but with specialised surgical instruments, more sophisticated operations could be carried out such as the removal of cataracts, draining of fluids, trephination, and even reversal of circumcision. Wounds were stitched following surgery using flax, linen thread or metal pins. Dressings were of linen bandages or sponges and either dry or wet, that is, soaked in wine, oil, vinegar or water and kept moist with a cover of fresh leaves. The most important surgeons were Heliodorus and Antyllus but very little of their written work survives.

Doctors also recognised that regarding injuries to the brain, heart, liver, spine, intestines, kidneys and arteries there was not much that could be done by even the most able practitioner. Consequently, it was advised not to get involved with these cases and damage one's medical reputation. Cases which were most commonly brought to the attention of doctors were ailments such as skin, digestion and fertility problems, bone fractures, gout (podagra), depression (melancholia), dropsy or fluid retention (leukophlegmasia) and even epilepsy (comitialis).

Famous Specialists

Aulus Cornelius Celsus (c. 25 BCE - c. 50 CE) in the 1st century CE wrote an encyclopedia which included a part on medicine, of which, only book seven De medicina survives. In it he mentions and critically assesses traditional remedies such as the old Greek practice of a steam bath perfumed with a herb of the mint family which aided sweating and revitalised the body, eating snakes to get rid of abscesses or, even more bizarrely, the belief that drinking the blood of a slain gladiator cured epilepsy. He advocated hot plasters of mallow root (hibiscum, malva) boiled in wine to treat gout. Celsus believed dietetics was the most important of the three branches of medicine. He pointed out that imminent death of the patient was indicated by pointing of the nose, sunken temples and eyes, cold ears and the skin of the forehead being taught and hard. He did confuse fever and diarrhoea as illnesses instead of symptoms and he had a penchant for blood letting but he did also recognise the value of massage and sweating. He divided food into that which cooled the patient (e.g. lettuce, cucumber, cherries and vinegar) and that which provided heat (e.g. pepper, salt, onions and wine). Generally, Celsus is rather unsympathetic with those who seek treatment and stresses the importance of a healthy outdoor lifestyle to keep the doctor away.

Scribonius Largus (c. 1 - 50 CE) from Sicily was a physician of emperor Claudius' entourage which visited Britain in 43 CE. Of the empiricist school, he wrote his Compositiones on drugs of the time which included a salve for arthritis, a recommendation for the trefoil plant against snakebites, and turtle or dove's blood as a cure for epilepsy. Largus, like many other authors, used the Greek terms for medicine and plants and he also supported the essential principles of the Hippocratic Oath.

Soranus of Ephesos (c. 60 - 130 CE) gave midwives and wet nurses advice in his Gynecology stating they should be literate, sober, discreet, knowledgeable of both theory and practice and not be influenced by superstition. He studied at Alexandria, practised in Rome and was part of the popular Methodist approach where importance was given in remedying a body too 'constrained' or too 'relaxed'. In his work he also reiterated the common advice to avoid pregnancy such as holding one's breath during intercourse or sneezing shortly after.

Galen of Pergamon (129 - c.216 CE) was an all-round scholar and physician who travelled a great deal in the Mediterranean, learnt his trade in a gladiator school and became a prolific writer of medical treatises which were translated into many other languages such as Hebrew and Armenian. For example, he gave advice for new mothers in his Prognosis, advised on the wisdom of soaking bandages in wine to sterilise them in his prolific commentaries on the Hippocratic Corpus, and helpfully advised on how to choose a good doctor in his Examinations of the Best Physicians. He was a favourite of the Imperial household from Marcus Aurelius to Septimius Severus and even claimed that the former, after solving a stomach problem, said of him that, 'we have one doctor, and he is a consummate gentleman'. Galen worked tirelessly using dissection to extend his knowledge and he also supported the idea in the Hippocratic Corpus that it was the imbalance of the four bodily fluids (or humours) of phlegm, yellow bile, black bile and blood that caused illness. This idea was coupled with the four qualities of heat, cold, wet and dry which underpinned all treatments and which would remain influential for the next 1500 years.

Conclusion

As with the Greeks, then, the Romans had no official medical training or qualifications and there was no orthodox medical approach. Methods and materials were down to the individual practitioner who gained the confidence of his patients through the accuracy of his diagnosis and prognosis case by case. The Roman medical specialists followed on from their Greek predecessors, documented that earlier tradition for the good of posterity and made advances, notably in surgery and anatomical knowledge. There were still many knowledge gaps and more than a few erroneous beliefs but Roman physicians and medical scholars had made such a push forward that their approach would remain the dominant one for another millennium.