Oribasius (c. 320-400/403 CE) was the physician and political advisor of the Roman emperor Julian the Apostate (r. 361-363 CE). A native of Pergamon, a rich and powerful Greek city in Mysia, he studied medicine and oratory and belonged to the high intellectual circle of Pergamon. Oribasius was an iatrosophist, which refers to a physician of a special rhetorical and philosophical knowledge, and a great admirer of Galen's medical knowledge and polymathy. His most famous work is Iatrikai synagogai or Collectiones medicae, a medical treatise of great significance.

Life

Oribasius or Oreibasius was born into a prominent family in Pergamon. From his childhood, he acquired a variety of learning experiences and broad knowledge that conduce to virtue. His biography was written by his personal friend Eunapius of Sardis, a Greek sophist and historian of the 4th century CE, in his Lives of the Philosophers and Sophists. According to Eunapius, when he reached early manhood, Oribasius studied medicine and oratory at Alexandria under the physician Zeno of Cyprus, one of the best teachers of the age, and practised in Asia Minor.

He had Magnus of Nisibis (the part of Antioch which lies beyond the Euphrates) and Ionicus of Sardis as fellow students. Magnus of Nisibis, also known as Magnus Medicus or Magnus Epigrammaticus, lived in Alexandria between 364-388 CE and was a healer and orator. He seems to have been influenced by Aristotle's theory on the nature of bodies endowed with volition and on the exercise of deliberate purpose, which means that doctors can persuade patients that they could decide as to whether to be well or ill. Ionicus, a son of a celebrated physician, attained to the highest degree of industry and diligence and won the admiration of Oribasius. He was an expert at pharmacy, anatomy, dissection, amputation, and post-operative bandaging and treatment. In addition to his practical knowledge of medicine, he was interested in philosophy, divination, oratory, and poetry.

Oribasius was considered as one of the most illustrious representatives of intellectual circles in Pergamon. He was married to a wealthy lady of high rank and had four children. His son Eustathius was also a physician, perhaps an archiatrus in the East in 373-374 CE. He was the dedicatee of one of his father's books. Unlike Oribasius, he was a Christian and the recipient of two of Saint Basil the Great's (l. 330-379 CE) letters: Ep. 151 (373 CE) and Ep. 189 (374-375 CE).

Career

In Pergamon, Oribasius met the future Roman emperor Julian the Apostate (l. 331-363 CE), the son of a half-brother of Constantine the Great (r. 306-337 CE). After his father’s death, Julian was placed by Constantius II (r. 337-361 CE) in the care of an Arian bishop, and from 342 CE, he was interned for six years in an imperial estate of Cappadocia. In the beginning, he was a Christian pious pupil, but his readings of the Greek classics led him to convert to polytheism, the worship of different gods and goddesses. Julian was bound by a strong friendship with Oribasius. Accordingly, he appointed him as his personal physician and head of his library.

In 355 CE, Oribasius accompanied Julian, who was proclaimed Caesar, to Gaul and Britain. When Constantius ordered the transfer of choice detachments to the east, the Roman army rebelled, and in February 361 CE, they proclaimed Julian Augustus. Julian’s elevation to Augustus was the result of military rebellion facilitated by Constantius’ death. Oribasius was closely involved in Julian’s coronation. He exercised significant political influence over the emperor and took an active part in his cultural program, including the restoration of paganism, the ancient Roman religion. He was nominated quaestor of Constantinople. During his quaestorship, he served as Julian’s sacred ambassador. Oribasius was the recipient of an oracle delivered at Delphi. This oracle made known the inability of Apollo to predict there again:

Tell the emperor, the splendid hall fell to the ground. Phoebus no longer has his house, nor the prophesying laurel, nor the speaking well. The speaking water has dried out.

Of it Myers wrote: "(It is) the last fragment of Greek poetry which has moved the hearts of men, the last hexameters which retain the ancient cadence, the majestic melancholy flow" (Abbott, 447). The authenticity of the Delphic oracle survives in the S. Artemii Passio [96.1284.45–47] probably from Philostorgius (368- c. 439 CE), an Anomoean Church historian of the 4th and 5th centuries CE, and in Cedrenus [1.532.8-10], a Byzantine historian of the 11th century CE. The oracle is mentioned by Gregorius of Nazianzus (329-389 CE), a Cappadocian Father, and explicitly confirmed by the Christian bishop Theodoret of Cyrus (393-458/466 CE), a theologian of the School of Antioch and biblical commentator, in his Ecclesiastical History.

The consultation of the Delphic oracle took place before the start of the Persian campaign. The expedition against the Persians offered the emperor the opportunity to solidify his position in the eyes of the eastern army. To prepare for the campaign, Julian moved in June 362 to Antioch CE. Given that he marched out of this city on 5 March 363 CE, the oracle must have been delivered during the last months of 362 CE when Julian strove to restore paganism. Seeing that there is no oracle delivered at Delphi between 362 and 394 CE when Theodosius I (r. 392-395 CE) banned all Panhellenic Games as being pagan events, one can conclude that Oribasius received the last Apollonian oracle.

Oribasius remained with Julian until Julian’s death. On 26 June 363 CE, in the battle of Samarra near Maranga, Julian was fatally wounded when the Sassanian army attacked his column. He received a wound from a spear that reportedly penetrated the lower lobe of his liver. He was treated by Oribasius, who has made every attempt to treat the wound. In all likelihood, he has irrigated the wound with a dark wine and applied a procedure known as gastrorrhaphy, the suturing of an intestine perforation. On the third day, a major haemorrhage occurred and the emperor died during the night.

In the wake of this event, Oribasius was the victim of Julian’s successors, who desired to take his life but shrunk from the deed. However, they deprived him of his properties and exiled him. Oribasius practised Roman medicine at the courts of the barbarians, where he showed the greatness of his medical knowledge and skills. Among his patients, he healed some from chronic diseases and snatched others from death’s door. Therefore, he was quickly promoted to the first rank at the courts of foreign rulers. As stated by Eunapius, he was recalled by the 'emperors', whose names are not mentioned. Bringing back Oribasius would have been "a part of the policy of exploiting 'hellenic' easterners as high official and ornaments of the régime" (Matthews, 115; Baldwin, 96). After he had gained permission to return, Oribasius recovered his original fortune from the public treasury with the consent of the later emperors and continued to exercise his profession until an advanced age.

Works

The works of Oribasius are not very original, often dealing with the collection of information and therapies used by the most famous doctors.

His surviving works are:

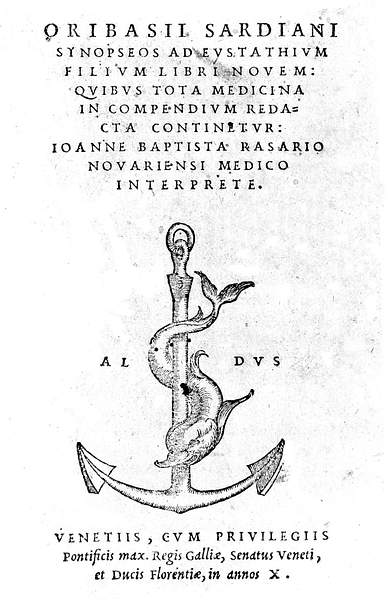

- Collectiones medicae - 25 of 70 books survive intact

- Synopsis for Eustathius

- Ad Eunapium

- Introductions to Anatomy

- Commentary on the Aphorisms of Hippocrates

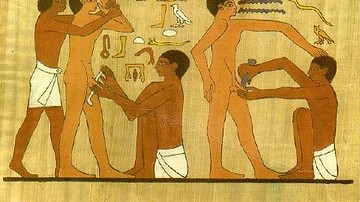

His principal work as a medical writer is Iatrikai synagogai or Collectiones medicae, which he wrote at the behest of Julian. The Collectiones medicae is a kind of encyclopedia comprising all the anatomical and physiological medical knowledge of the time, as well as the most effective techniques in the field of therapy and pharmacology. It represents a vast compilation of excerpts from Galen, which have not survived, and of the writings of renowned physicians from antiquity to the 4th century CE, such as Philagrius of Epirus (300-340 CE), a pupil of a physician named Naumachius and author of 70 volumes of which only a few fragments have survived, and Adamantius of Alexandria (c. 412/415 CE), an iatrosophist and author of a Greek treatise on physiognomy and another called De ventis.

The excerpts were often accompanied by relevant remarks by Oribasius. The importance of the work resides essentially in the breadth and accuracy of the excerpts selected, which embraced all the fields of medicine as well as the relationship of humanity with the environment and diseases. Of the 70 or 72 books of the Collectiones, only 25 survive intact. The rest can be in part reconstructed from the Synopsis for Eustathius and the treatise Ad Eunapium. The first, in nine books, is an abridged synopsis of the 70-volume work, dedicated to his son Eustathius and addressed to those who have to travel for practical purposes. The second is a collection of easily procured medicines, dedicated to Eunapius, his friend and biographer. This compendium provides a description of hygiene and diet, the properties of drugs, lists of particular drugs, as well as information about the anatomy of the human body, diseases, and related treatments. These two compendia are conceived as reference manuals, with the purpose of helping the reader in case of medical emergencies. In fact, the author focuses more on therapy than on etiology or pathology.

Among the known lost works are:

- Anatomy of the Intestines

- On Diseases

- To the Perplexed Physicians

- On Royal Rule - a work not dealing with medicine

Importance & Legacy

Oribasius provides us with a precious source on the history of ancient and early Byzantine medicine. His works are based on clinical observations and the experimental method of all great masters, and Byzantine medical writers constantly cited and extracted parts of Oribasius’ work in their writings. Above all, he paved the way for Galenism, as he was the first to consider Galen’s works as fundamental for the progress of medicine. Thanks to his works, a considerable part of many medical writings has not been lost The Synopsis for Eustathius and the Ad Eunapium have served as a model for future compendia and were translated into Latin in Ostrogothic Italy as early as the 5th century CE and Syriac and Arabic in the Islamic world.