The Renkioi Hospital, was a complex of innovative prefabricated buildings designed by Isambard Kingdom Brunel for use during the Crimean War (1853-56). Brunel had been moved by the heavy casualties and even higher deaths via disease during the war, and his 1,000-bed hospital included the latest ideas in ventilation and sanitation as advocated by such nursing pioneers as Florence Nightingale.

The Crimean War & Florence Nightingale

The Crimean War was fought between Russia and the Ottoman Empire whose allies included Great Britain. Russia had long been seeking to grab territory from the crumbling Ottoman Empire, and it invaded the Danubian principalities (the Ottoman tributaries of Moldavia and Wallachia) in 1853. Both Britain and France declared war on Russia when it refused to withdraw. An allied expeditionary force was sent to attack Sevastopol on the Black Sea Coast of the Crimea, which was Russia's main naval base in the region. In 1854, a siege of Sevastopol began which lasted a year. The war became a tale of military mismanagement and incompetence, most infamously exampled by the disastrous Charge of the Light Brigade during the Battle of Balaclava in October 1854. The allies won important victories but at a tremendous cost in casualties and lives.

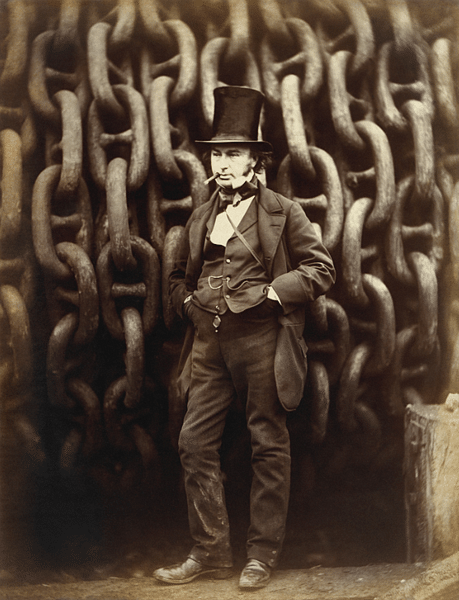

It was horror stories of the dreadful fate of thousands of British soldiers – wounded in battle, underfed, underclothed, lacking in medicine, and battling outbreaks of cholera – that motivated the famed engineer Isambard Kingdom Brunel (1806-1859) to do something to help. Journalists like William Howard Russell (1820-1907) used the new electrical telegraph to send home shocking reports of the terrible conditions for all sides in the war. In a mere six months from 1854 to 1855, of the 56,000 British soldiers sent to the Crimea, 34,000 died, and for some 16,300 of these, the cause was disease. The English nurse Florence Nightingale (1820-1910) was also motivated to help, and she became the supervisor of nursing in British army hospitals and an outspoken critic of government and military ineptitude. The death rate of patients in military hospitals had been 42%, but Nightingale reduced this figure with her strict regime of hygiene, good ventilation, and dietary care for patients, greatly reducing deadly cases of cholera, dysentery, and typhus. Despite her successful new regime, Nightingale lobbied the government for new and better medical facilities for the war wounded.

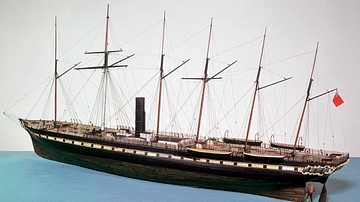

Brunel's contribution to the war effort was two-fold: the giant steamship he designed and built, SS Great Western, was used as a troopship, and he invented an entirely new kind of hospital. Brunel also drew up plans for floating batteries of cannons that could be used on water to fire at coastal fortresses, but the Admiralty, a rather ponderous institution not known for its rapid innovation, neither approved nor disapproved of the plans, and so this third area of assistance came to nothing.

A Prefabricated Design

The main hospital for the British Army during the Crimean War was at Scutari, but its reputation was so bad that more than one source described it as "a national disgrace" (Bryan, 142). Scutari was one of many others areas of incompetence during the conflict that led to the fall of the government in January 1855. A new government led by Lord Palmerston at least responded to the public outcry and launched an investigation into conditions in the Crimea, conducted by a Sanitary Commission. In February, things began to move in a better direction when Brunel was contacted by Benjamin Hawes, the Permanent Undersecretary at the War Office who was also a friend and brother-in-law of Brunel. Given the urgent need, the engineer was asked to design an entire field hospital which could be shipped to the Crimea and made on-site as quickly as possible. Acutely aware of the hardships being endured in the ongoing conflict, Brunel took just a couple of weeks to submit his plans for the hospital to the War Office.

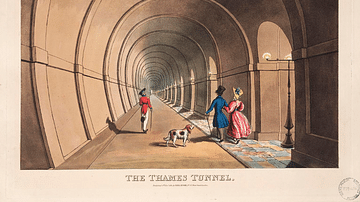

Brunel's hospital was to be made of prefabricated sections which could be easily shipped to their destination and then assembled without the need for skilled carpenters, joiners, and plumbers. The idea of prefabricating pieces was likely inspired by the success of the giant Crystal Palace, the host of the 1851 Great Exhibition in London. The Crystal Palace was designed by Sir Joseph Paxton (1801-1865), based on his own smaller structure of glass and iron at the home of the Duke of Devonshire, Chatsworth House. It, too, had had to meet the requirement of being a temporary building that was quick to build. The Crystal Palace had both glass walls and roofing supported by iron framing set on concrete foundations; it took just four months to build.

Brunel had himself used partially prefabricated elements to build Paddington Station at the London end of his Great Western Railway. Prefabrication went well with the modern idea that buildings should prioritise form and function over the purely decorative. In addition, the idea of prefabrication appealed to engineers like Brunel who saw the new capabilities of mass-producing machines during the Industrial Revolution as a more efficient and cost-effective substitute for skilled labour.

Planned Facilities

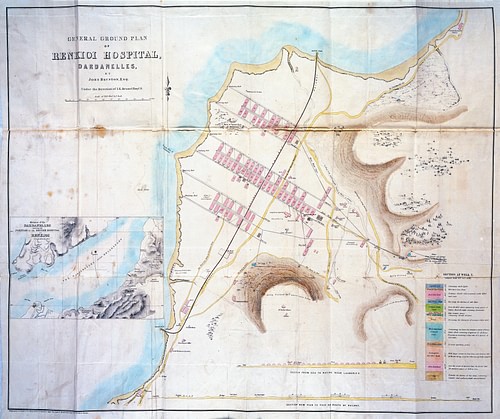

Brunel came up with the idea of several ward buildings all built to the same specifications. The individual pieces of the buildings were made of wood and specifically designed so that each piece was not too heavy for one or two men to carry and put in the correct position on site. Each building would hold 48 beds divided equally into two wards, although Brunel allowed for the possibility that each building could be easily extended if required. The total capacity for the hospital would be around 1,000 beds. The design included facilities for washing and good sanitation with plenty of water taps, bathrooms (including specially adapted baths that could be used by invalids), stoves for heating water and the wards, lavatories, drains, and good ventilation provided by fans. There were, too, additional iron buildings devoted to cooking and laundry. Brunel forgot no detail, even including toilet paper in his master plan of what went where once everything was assembled.

All of these elements seem rather simple and obvious nowadays, but at the time, they were revolutionary. Medical treatment in the field of battle was still rudimentary at best, often involving canvas tents or a private villa requisitioned for the purpose of serving as a temporary hospital. The availability of equipment was entirely dependent on the foresight of individual doctors. This was also a period when disease was still the biggest killer in warfare, not bullets, and such organisations as the Red Cross had yet to be founded (1863). The Renkioi plan was certainly breaking new ground.

The hospital design was approved by the War Office, and Brunel set about building the component parts and then planning the tremendous logistics involved of not only shipping the prefabricated elements to the Crimea – around 11,500 tons of material in all – but also ensuring the right tools and assembly instructions went with them. Brunel's design meant that men did not need to be specially trained to build the hospital at its final destination. All that was needed to put the hospital buildings together was a number of ships for transportation, muscle power on site, and a spot with relatively flat ground.

Saving Lives

Brunel's assistant John Brunton was given the responsibility of supervising the construction of the hospital at a new location, Renkioi (sometimes spelt Renkoi) rather than at Scutari 100 miles (160 km) distant. Brunton was given the rank of major, and he headed to the Crimea in March with a team of 30 members of the Army Works Corps. Meanwhile, Brunel organised the shipment of the prefabricated buildings so that they arrived on site on 7 May.

The first buildings and first 300 beds were ready by mid-July of 1855, but the conduct of the war continued to be as inefficient as previously, and no patients were admitted to the hospital until 2 October. The problem was that Renkioi, selected for its flat ground, was too far from the fighting front, and patients had to come in by ship. The hospital itself was not entirely finished until December when all 1,000 beds were made available. The medical officer in charge of Renkioi, Dr Edmond Parkes, gave the following description of the facilities:

The construction of the hospital was admirably adapted for the men recovering from illness. As all the wards were on the ground, as soon as a man could crawl he could get into the air, either in the cool and sheltered corridor or in the spaces round the hospital.

The anticipations we had formed of the health of the spot and of its adaptability for a hospital were quite confirmed by the experience of more than a year. The winter was mild and the climate seemed especially adapted for pulmonary complaints, of which we had a large number. The changes of temperature, it is true, were very sudden and great, but as the men had warm wards, these changes were not felt and there were few days in all but the most delicate and consumptive patient could not get out into the sheltered corridor for a short time during the day. (Shelley et al, 122)

Legacy

By February 1856, the fighting had ceased. The Treaty of Paris ended the Crimean War with Russia agreeing to respect the independence of the Danubian principalities. Even though Brunel's hospital had been open only for a relatively short time, it had done great work. In total, 1,351 patients had spent time in the hospital, and all but 50 made a recovery. This was an astonishing rate of success compared to the situation previously. Nightingale and Brunel had never actually worked together, probably because the nurse had made enemies in high places with her public criticism of the management of the war and the treatment of the wounded, but this unlikely pair, a nurse and an engineer, had managed to transform attitudes to medical care in war zones. Evidence of this change in approach was seen just a few years later during the American Civil War (1861-65) when Brunel's hospital design was adopted by the Union Army.