Pausanias was a Greek author, historian, and geographer of the 2nd century CE who journeyed extensively throughout Greece, chronicling these travels in his Periegesis Hellados or Description of Greece. His ten volumes of observations are treasured by both historians and archaeologists for their in-depth depiction of ancient Greece. He was far more than just a geographer; his travelogues included not only a description of an area's monuments, architecture and works of art but also its history, including the daily life of its people, ceremonial rites, customs, legends and folklore. Pausanias' work influenced the development of classical archaeology more so than any other text.

Life

Although little is known of Pausanias' early life, and his birth year is hard to pin down (speculations range between 110 CE, 115 CE, and 125 CE), it appears he was born in Magnesia ad Sipylum, a city in the province of Lydia located in western Asia Minor. Because of his ability to travel so extensively, many assume he was well-educated and from a privileged class. There is some disagreement over when he began his Description of Greece. Some believe it may have been begun as early as 143 CE (which would have made him less than 20 years old) while others point to the more believable 155 CE. However, Pausanias seems to have ended his writing before 180 CE since no event after 176 CE is mentioned, and his death is generally placed in 180 CE.

While there may be some disagreement over when he began his travels, there is no doubt that his youth was spent during the reign of the Roman emperor Hadrian (117 CE – 138 CE) who was an admirer of all things Greek - especially the ancient Greek monuments of the Archaic and Classical periods.

The emperor's nurturing of a revival of Greek culture would have a profound effect on the young Pausanias (and with him many others); instead of focusing on events from his own time, Pausanias was drawn to the monuments and stories from the heyday of the independent Greek city-states.

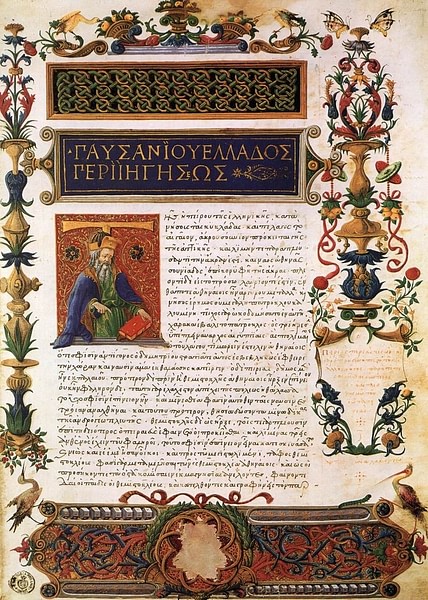

Description of Greece

Before writing his Description of Greece, which he approached geographically, Pausanias toured the Mediterranean - Asia Minor, Syria, Palestine, Egypt, and even Italy, studying its people and their customs. Oddly, his travelogue does not cover all of Greece, concentrating only on a sizeable portion of its central and southern parts - primarily the Peloponnese, omitting Aetolia and the islands. His ten volumes comprise sections on the city-states of Attica (including Athens), Corinth, Argolid, Laconia, Messenia, Elis, Archaea, Arcadia (including Olympia), Boeotia, Phocis (including Delphi). Pausanias was mainly concerned with all things unique about an area - monuments, customs, and folklore - and because of his great interest in the religious side of things, like temples and sanctuaries, to some readers his Description might appear more like a 'pilgrimage' than a travelogue. Typical of his observations with respect to folklore are his comments concerning a statue of Apollo in Athens:

There is further a sanctuary of Apollo surnamed Delphinius. The story has it that when the temple was finished with the exception of the roof Theseus arrived in the city, a stranger as yet to everybody. When he came to the temple of the Delphinian, wearing a tunic that reached to his feet and with his hair neatly plaited, those who were building the roof mockingly inquired what a marriageable virgin was doing wandering about by herself. (1.19.1)

In the Athenian market-place among the objects not generally known is an altar to Mercy, of all divinities the most useful in the life of mortals and in the vicissitudes of fortune, but honored by the Athenians alone among the Greeks. And they are conspicuous not only for their humanity but also for their devotion to religion. (1.17.1)

Reliability

Considering his extensive travels to the places he wished to discuss, and extensive studies of his chosen topics, Pausanias is generally seen as a valuable eyewitness when it comes to the status-quo of his own time. The information he gives regarding sites and monuments is certainly easily verifiable, as they were and are pretty accessible for visitors. For his revisiting of old myths and customs of areas, Pausanias would have had to rely on his research (and thus, on other people supplying this information), so his accuracy here would depend on his sources, but overall his interpretations have stood the test of time. Overall, considering his invaluable status as an archaeological source, Pausanias appears to be fairly reliable. However, it should be noted that Pausanias made a strict selection of what he included in his Description, only including the sites and monuments he deemed to be the most noteworthy, which, for him, often meant leaning more towards Greece's heyday and the religious side of things than to his own time.

Moreover, Pausanias himself was, like anyone else, coloured by his upbringing and the political and cultural context he grew up in: he was a Greek, while Greece was under Roman rule. Long before Pausanias' birth, Rome had conquered Greece in the Macedonian Wars. And, while the Romans loved all things Greece, even using Greek tutors for their children and studying philosophy and rhetoric in Athens, many Greeks resented their presence. Historian Mary Beard in her book SPQR stated that the Greek author and orator Publius Aelius Aristides praised Roman rule in a speech given before the Emperor Antonius Pius claiming that Rome had surpassed all previous empires bringing peace and prosperity to the whole world. According to Beard, Pausanias, however, gave Rome a different assessment; he ignored any mention of buildings erected by Romans or with Roman money, in an attempt to turn back the clock and re-create an image of a Rome-free Greece. So, however extensive his studies may have been, his writings include an obvious anti-Roman attitude, which must be taken into account when using the work as a source.

The exception to the anti-Roman rule in his work is when Pausanias acknowledges the contributions of the Roman emperor Hadrian (who happened to love Greece):

Before the entrance to the sanctuary of Olympian Zeus – Hadrian the Roman emperor dedicated the temple and the statue, one worth seeing, which in size exceeds all other statues save the colossi at Rhodes and Rome …. (1.18.6)

Later, he said that Hadrian built other buildings for the Athenians - a temple for Hera and Zeus as well as "a hundred pillars of Phrygian marble" (1.18.9).

Legacy

Although little is known of his life aside from his writings, Pausanias' work has ended up influencing the development of classical archaeology to a larger degree than any other text. His detailed descriptions give his readers an insight into a Greece whose ancient monuments are either long gone or have fallen into various states of ruin. As such, Pausanias helps illustrate the complexity of the Ancient Greek world.