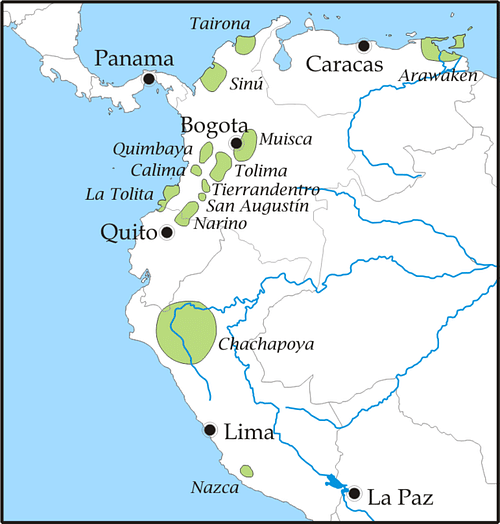

The Nazca Civilization flourished on the southern coast of Peru between 200 BCE and 600 CE. They settled in the Nazca and other surrounding valleys with their principal religious and urban sites being Cahuachi and Ventilla, respectively. The culture is noted for its distinctive pottery, textiles, and the geoglyphs made on the desert floor known as Nazca lines.

Overview

The Nazca were contemporary with, and then outlasted, the Paracas culture and many Paracas sites have been discovered beneath Nazca settlements. Politically, the Nazca civilization has been described as a collection of chiefdoms occasionally acting in unison for mutual interest rather than as a single unified state. Or as M.E. Moseley puts it, "individuality - with cultural coherence, but without large-scale or integrated power - were Nazca hallmarks". This interpretation is reinforced by the art and architecture of the Nazca which displays common themes across settlements but at the same time there is a general lack of uniform town planning or evidence of centralization. The maximum population of the Nazca has been estimated at 25,000 people, spread across small villages which were typically built on terraced hillsides near irrigated floodplains.

As they developed, the Nazca extended their influence into the Pisco Valley in the north and the Acari Valley in the south. In addition, as llamas, alpaca and vicuna do not survive in the coastal areas the use of their wool in Nazca textiles is evidence that trade was established with highland cultures. In addition, Nazca mummies have been discovered wearing headdresses made with the feathers of rainforest birds, once again, illustrating that goods were traded across great distances.

Graves, often placed up to 4.5 metres deep and accessed via a shaft, are the richest source of Nazca artefacts and reveal many aspects of the culture. Fine pottery and textiles were buried with the dead and with no particular distinction between male and female burials. The deceased is mummified, carefully wrapped in textiles and usually placed in a seated position, skulls sometimes display deliberate elongation, and we know the Nazca wore tattoos. Tombs, especially shaft ones lined with mud bricks, could be re-opened and more mummies added, perhaps indicating ancestor worship. Caches of trophy-heads often accompany the mummy, many showing signs of trephination which allowed several to be strung on a single cord as illustrated in pottery designs. Trophy-heads are also frequently incorporated into textile designs, especially in miniature and as border decoration. There were also burials of what appear to be sacrificial victims. These have the eyes blocked and excrement was placed in the mouth which was then pinned shut with cactus needles. Alternatively, the tongue was removed and kept in a cloth pouch.

Weakened by a generation-long drought in the 5th century CE, the Nazca were eventually conquered by the Wari - who assumed many of their artistic traits - and Nazca settlements, thereafter, never rose beyond provincial status.

Ventilla

Ventilla was the Nazca urban capital and covered over 2 square kilometres (495 acres) and included ceremonial mounds, walled courts, and terraced housing. To fight the ever-present threat of drought the Nazcans built an extensive network of underground aqueducts, galleries, and cisterns in order to ensure a good water-supply during the dry season and minimize evaporation. These were reached by impressive descending spiral ramps and lined with river cobbles.

Cahuachi

Founded c. 100 BCE, Cahuachi, on the south bank of the Nazca River, 50 km inland, was a site of pilgrimage and the Nazca religious capital. It was probably first considered sacred because it was one of the few locations with a guaranteed year-round water supply. The lack of domestic architecture indicates it was not used as a place of habitation.

The sacred site covers 11.5 square kilometres (2,841 acres) and has around 40 large adobe mounds which take advantage of natural hills. The largest mound, known as the Great Temple, is over 20 metres high. All of the mounds have an adjoining plaza and are topped by adobe walls. The largest plaza measure 47 x 75 metres. A low wall, 40 cm high, surrounded the main sacred precinct. Posts and postholes across the site suggest canopies protected worshippers from the sun. Textile scenes also suggest that religious gatherings were connected to harvest festivals, and piles of rubbish consisting mostly of pottery shards at the site indicate ritual feasting. This rubbish was deliberately left so that it became a part of the mound. Consequently, the larger the mound, the more it had been used in rituals. Some mounds also contained burials and large pots containing fine textiles given as religious offerings.

More details of the religious ceremonies that may have been carried out at Cauachi are depicted in Nazca art, especially on pottery, and many are scenes involving shamans. These religious figures, in a drug-induced trance, appealed to nature spirits to guarantee favourable conditions for agricultural abundance. Music was an important part of these rites, as is evidenced by the abundance of ceramic drums and panpipes in the archaeological record. The principal Nazca god seems to have been the Oculate Being who is represented in art as a flying deity figure wearing strings of trophy-heads. He is frequently depicted in pottery and textile designs in a horizontal position with streamers flowing from his body. Large staring eyes and a snake-like tongue are other typical features.

Nazca Lines

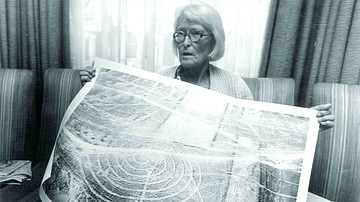

The Nazca drew geoglyphs and lines across the surrounding deserts and hills which were either stylized drawings of animals, plants, and humans or simple lines which connected sacred sites or pointed to water sources. Their exact purpose is disputed, but the most widely held theory is that they were designed to be walked along as part of religious rites and processions.

These ancient lines were made remarkably easily and quickly by removing the oxidised darker surface rocks which lay closely scattered across the lighter coloured desert pampa floor. Most designs are only visible from the air, but some were made on hillsides and so are visible from the ground.

Lines could be single - both straight and curved - or in groups and could cross each other in complicated networks. The width and length of lines can vary; one of the longest straight lines is 20 km long and the total combined length of Nazca lines has been estimated at over 1,300 km. Those lines used to describe a specific shape are generally composed of a single continuous line. Designs could be geometric shapes or animals such as a hummingbird, spider and even a killer whale. Trees, plants, and flowers were another subject, as were human figures.

The scale of the designs can be huge; many are at least the size of a sports field. They were also made over several centuries and very often newer designs overlap and ignore older ones which would strongly suggest a lack of long-term and unified planning and, therefore, that they were made by different groups at different times and served more than a single purpose.

Nazca Pottery

The Nazca have achieved a reputation for great artistry and their finely worked pottery is an excellent example. Vessels were thin-walled and could take on a wide variety of shapes. Distinctive forms include the double-spouted containers with a single handle and generally bulbous vessels without a flat bottom or base. Bowls, beakers, jars, effigy drums, and panpipes were also common. There were also vessels in the shape of human heads, no doubt inspired by the Nazca practice of taking trophy-heads following battles.

Influenced by the earlier Paracas culture designs, Nazca pottery vessels were decorated with a slip (before firing) to produce a wide array of vividly rendered patterns, gods, shamanic imagery, crustaceans, condors, monkeys, and mythical transformational creatures, especially felines. The Nazca went on to create their own unique style and designs evolved from naturalistic to highly ornamented and then to highly abstract forms. Often the design covers the entire vessel producing a wrap-around three-dimensional effect, even a narrative, for example, with battle scenes. Designs might also exploit the contours of the vessel, for example, a nose on a protruding part. Designs can also overlap each other to create the illusion of space and depth.

Maroon, light purple, and blue-grey were a favourite choice of colours but a very wide range was used, more, in fact, than in any other ancient Andean culture. Backgrounds were usually in white, red, or black. Outlining figures in black was another feature and another example of the Nazca delight in linear design. A final polishing gave the colours a fine shine.

Nazca Textiles & Metalwork

The Nazca, like many cultures in South America, were fond of not only wool weaving and embroidery but also of painting plain cotton cloth with an array of colourful images and motifs. Textiles have survived remarkably well, thanks to the extremely dry climate, and they illustrate that Nazca weavers possessed the full range of Andean techniques and employed an astonishing range of colours and shades to produce intricate and detailed designs. Figures were especially popular in designs and most often are depicted participating in harvest scenes which show such foodstuffs as maize and beans. Animal figures, similar to those in the geoglyphs and pottery designs, were also a popular subject. Looms, spindles, needles, cotton balls, and pots of dyes have all been excavated from Nazca settlements.

Nazca metalworkers beat gold into thin sheets which were cut to create silhouettes. Preferring to keep surfaces smooth and reflective, only a little repoussé work provides sparing decoration. Masks were produced which were worn over the mouth and made the wearer appear to have a golden beard and whiskers. Gold full-face masks, hair plumes, and nose and forehead ornaments were also produced. These gold masks transform the face of the wearer and recall the transformation ceremonies carried out by the shamans who were such a popular subject in Nazca art.